On Kimberly Repp’s office wall is a sign in Latin: Hic locus est ubi mors gaudet succurrere vitae. This is a place where the dead delight in helping the living.

For medical examiners, it’s a mission. Their job is to investigate deaths and learn from them, for the benefit of us all. Repp, however, isn’t a medical examiner; she’s a Ph.D. microbiologist. And as the epidemiologist for Washington County in Oregon, she was accustomed to studying infectious diseases like flu or norovirus outbreaks among the living.

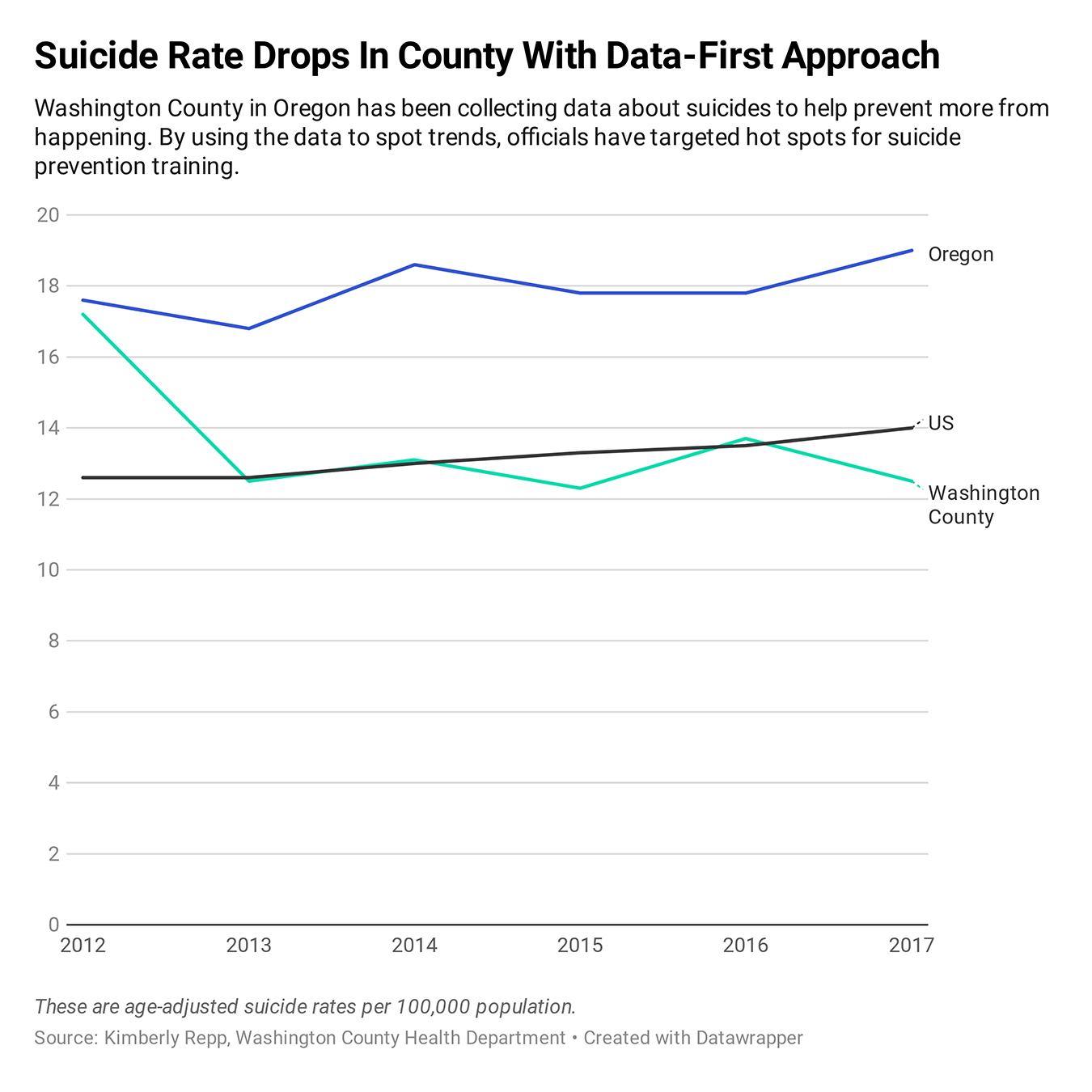

But in 2012 she was asked by county officials to look at suicide. The request led her into the world of death investigations, and it also appears to have led to something remarkable: In this suburban county of 600,000 just west of Portland, the suicide rate now is going down. It’s remarkable, because national suicide rates have risen despite decades-long efforts to reverse the deadly trend.

While many factors contribute to suicide, officials here believe they’ve chipped away at this problem through Repp’s initiative to use data — very localized data that any jurisdiction could collect. Now Repp’s mission is to help others learn how to gather and use it.

Northern California’s Humboldt County, where the suicide rate is higher than the statewide average, has begun implementing a system like Repp’s. Officials there have identified several unexpected locations, including public parks and motels, where people have died by suicide. They can now turn those sad facts into action plans.

New York state has just begun testing a similar system, and Repp has received inquiries from Utah and Kentucky. Colorado, meanwhile, is using its own brand of data collection to try to achieve the same kind of turnaround.

Following The Death Investigators

Back in 2012, when Repp looked at the available data — mostly statistics reported periodically to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — she could see that suicide was a big problem and that rates were highest among older white men. But beyond that, the data didn’t offer a lot of guidance. Plus, it lagged two years behind.

She returned to her bosses. “I can tell you who has the highest suicide rate, but I can’t tell you what to do about it,” she recalled telling them. “It’s too broad.”

So she turned to the county medical examiner’s death investigators. They gather information at every unnatural death scene to determine the cause (say, drowning or gunshot) and manner (homicide, suicide, accident). It’s an important job, but a grim one, and it tends to attract unusual personalities.

Repp mustered the courage to introduce herself to one of the investigators, Charles Lovato. “I said, ‘Hi, my name is Kim and I was hoping to go on a death investigation with you.’ And he’s like, ‘You’re that weirdo that does outbreak investigations, aren’t you?’ And I’m like, ‘You’re the weirdo that does death investigations.’”

The gambit worked. Repp accompanied Lovato on his grim rounds for more than a year. “Nothing can prepare you for what you’re going to see,” she said. “It gave me a very healthy dose of respect for what they do.”

She studied the questions Lovato asked friends and family of the deceased. She watched how he recorded what he saw at the scene. And she saw how a lot of data that helped determine the cause and manner of death never made it into the reports that state and federal authorities use to track suicides. It was a missed opportunity.

On the wall of Washington County epidemiologist Kimberly Repp’s office is a sign in Latin: Hic locus est ubi mors gaudet succurrere vitae. This is a place where the dead delight in helping the living.(Adam Wickham for KHN)

Collecting Data On The Dead To Save Lives

Repp worked with Lovato and his colleagues to develop a new data collection tool through which investigators could easily record all those details in a checklist. It included not only age and cause of death, but also yes/no questions on things like evidence of alcohol abuse, history of interpersonal violence, health crises, job losses and so on.

In addition, the county created a procedure, called a suicide fatality review, to look more closely at these deaths. The review is modeled on child fatality reviews, a now-mandatory concept that dates to the 1970s. After getting the OK from family members, key government and community representatives meet to investigate individual suicides with an eye toward prevention. The review group might include health care organizations to look for recent visits to the doctor; veterans’ organizations to check service records; law enforcement; faith leaders; pain clinic managers; and mental health support groups.

The idea, Repp said, isn’t to point fingers. It’s to look for system-level interventions that might prevent similar deaths.

“We were able to identify touchpoints in our community that we had not seen before,” Repp said.

For example, data revealed a surprising number of suicides at hotels and motels. It also showed a number of those who killed themselves had experienced eviction or foreclosure or had a medical visit within weeks or days of their death. It revealed that people in crisis regularly turn their pets over to the animal shelter.

But what to do with that information? Experts have long believed that suicide is preventable, and there are evidence-based programs to train people how to identify and respond to folks in crisis and direct them to help. That’s where Debra Darmata, Washington County’s suicide prevention coordinator, comes in. Part of Darmata’s job involves running these training programs, which she described as like CPR but for mental health.

The training is typically offered to people like counselors, educators or pastors. But with the new data, the county realized they were missing people who may have been the last to see the decedents alive. They began offering the training to motel clerks and housekeepers, animal shelter workers, pain clinic staffers and more.

They teach trainees to recognize signs of distress and how to ask people if they are in crisis. If the answer is yes, the trainees’ role isn’t to make people feel better or provide counseling. It’s to call a crisis line and let the experts take over from there.

Since 2014, Darmata said, more than 4,000 county residents have received training in suicide prevention.

“I’ve worked in suicide prevention for 11 years,” Darmata said, “and I’ve never seen anything like it.”

The sheriff’s office has begun sending a deputy from its mental health crisis team when doing evictions. On the eviction paperwork, they added the crisis line number and information on a county walk-in mental health clinic. Local health care organizations have new procedures to review cases involving patient suicides, too.

From 2012 to 2018, Washington County’s suicide rate decreased by 40%, preliminary data shows. To be sure, though, 68 people died by suicide here last year, so preventing even a handful of cases can lower the rate quite a bit.

Taking The Idea Elsewhere

Repp cautions that the findings can’t be generalized. What’s true in suburban Portland may not be true in rural Nebraska or the city of San Francisco or even suburban New Jersey, for that matter. Every community needs to look at its own data.

In Humboldt County, Calif., health officials estimate that 435 people died by suicide between 2005 and 2018 — the most common methods being hanging, drugs and firearms. About 18% of county residents reported suicidal feelings between 2012 and 2016 — twice the state average, according to the California Health Interview Survey, a long-running health study.

The county’s public health manager, Dana Murguía, said she and her colleagues have taken “deep dives” into the factors surrounding the suicides of county residents.

Notably, more than half of people over age 50 who died by suicide also had a physical health problem. Among younger people, nearly 40% grappled with addiction. Still others faced eviction or homelessness.

County epidemiologists would review suicide notes, medical and mental health records obtained from the coroner or family members and look for other factors involved.

Murguía had been frustrated for some time that local prevention plans weren’t making a dent. “I said, ‘We don’t need another plan. We need an operations manual.’ That’s what I feel Dr. Repp has given us.”

IF YOU NEED HELP

If you or someone you know is thinking about suicide, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255, or use the online Lifeline Chat, both available 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

California Healthline senior correspondent Barbara Feder Ostrov contributed to this report.

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.