BURBANK — Matt Fairchild, 46, is in near constant pain. Advanced melanoma has spread to his brain and bones. He takes 26 medications a day and rarely leaves his house except to go to doctors’ appointments.

Fairchild, a retired army sergeant, refuses to say he is fighting a battle against cancer, because he knows it’s one he will lose. He’s not sure how long he has to live, but he knows this: He doesn’t want to spend his last days in agony.

In October, California became the fifth state to allow terminally ill patients to end their lives with prescriptions from their doctors after months of contentious debate. Religious groups and disability rights activists fought against the law and tried unsuccessfully to get a referendum on the ballot to overturn it.

Late last week the bill’s authors announced that the aid-in-dying law would take effect June 9.

Fairchild said he feels calmer knowing the law will become effective in just a few months. When it’s time, he said, having a prescription will enable him to say goodbye to family and die in his sleep instead of suffering through intense pain, nausea or seizures.

“It gives me so much peace of mind because there is a date,” Fairchild said. That means once they stop treatment, or run out of options, “I don’t have to worry about hurting.”

As the implementation date nears, medical groups, supporters, legislators and others are working to raise awareness of the new right-to-die law and ensure all terminally ill patients will have access to it. They are holding webinars, panels and town hall meetings, distributing information and setting up telephone lines. And they are encouraging patients like Fairchild to discuss with their doctors whether a lethal prescription might at some point be right for them.

Sen. Bill Monning (D-Carmel), one of the authors of the law, said he was pleased that it now has an effective date and patients will have the option to avoid “insurmountable pain and suffering.” The forms are already in place and Monning said he expects patients to begin coming forward.

“There are families who have been calling us wanting to know if it will be available to a loved one,” Monning said. But he acknowledged that some may not make it until June. One of the law’s most ardent supporters, former Los Angeles Police Department Sergeant Christy O’Donnell, died last month of lung cancer.

“There are going to be people in these 90 days who unfortunately won’t be beneficiaries of the act,” Monning said.

Compassion & Choices, a medical aid-in-dying advocacy group that pushed for the law, recently launched a bilingual campaign, a speaker’s bureau and a free hotline for people who want more information. The group also has a confidential consultation program for doctors.

The organization is sending out volunteers to saturate the state and get the word out, said Kat West, its national director of policy and programs. But there is a lot of work ahead,” she said. “It is one thing to pass a law,” she said. “It is a whole other thing to have access to that law.”

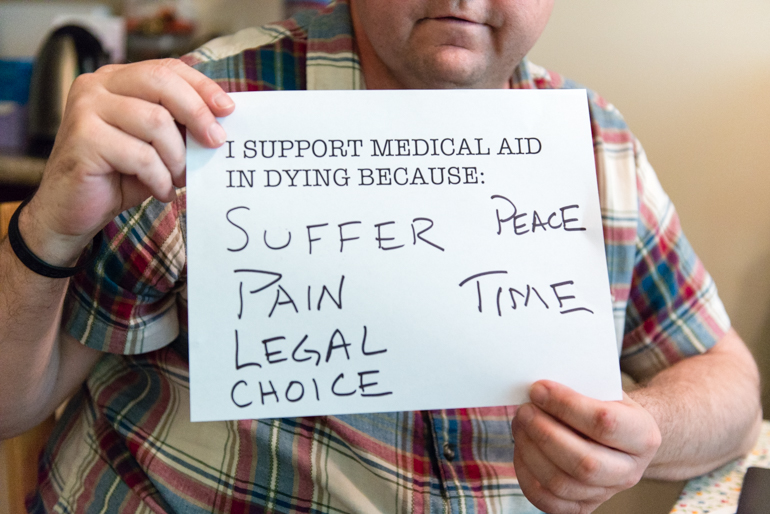

Fairchild holds a sign showing why he supports medical aid in dying. The 46-year-old Burbank resident wants to have the right to die if the pain from his melanoma becomes unbearable. (Heidi de Marco/KHN)

Under the law, patients can get fatal prescriptions only if they are mentally competent and have six months or less to live. To get the prescription, a patient must submit two oral requests — 15 days apart — to the attending physician, and one written request.

Wolf Breiman, who has two types of cancer — tongue and blood — said he is not yet considered terminal but plans to get a prescription when eligible. Breiman said he thinks he won’t use it unless his suffering becomes so bad it overcomes his will to live.

“I am 88 years old and I have got two cancers,” he said recently from his home in Ventura. “You can imagine why I am very interested in having this law become accessible.”

Breiman said he feels less anxious knowing that June isn’t far off. The retired landscape architect is in the middle of eight weeks of radiation for the mouth cancer, which leaves him exhausted and makes it difficult to swallow. “I’m hoping I will be OK until this becomes available,” he said. “I might be able to spare myself a great deal of suffering.”

Fairchild takes 26 medications each day. The combination of supplements and pain medication help ease his pain symptoms associated with his melanoma. (Heidi de Marco/KHN)

California follows Oregon, Washington, Vermont and Montana in approving lethal prescriptions. Despite the experience of other states, it still is unclear how the law will play out in California, said Ben Rich, an emeritus professor of internal medicine and bioethics at the UC Davis School of Medicine. He said he expects some health institutions to be supportive and others to be unsupportive, leading to inconsistency around the state.

Either way, Rich said he doesn’t think the law will result in a large number of physicians prescribing the medication. “But it does mean that many, many more physicians are going to have to figure out how to talk to patients when the patients raise the question,” he said.

“Physicians are going to have to either bring themselves up to speed on end-of-life options … or they need to know where to refer patients.”

Medical groups have already started educating their members about the law and other end-of-life options. The California Medical Association issued a document earlier this year that explains to doctors and patients how the law works. It answers questions such as, “Does The Act Specify What Aid-In-Dying Drug Can Be Prescribed?” (no) and “Can An Interpreter Be Used?” (yes).

Ted Mazer, an officer of the association, said doctors across the state are grappling with their feelings about the law and whether they will be comfortable prescribing medication. Personally, Mazer said he wouldn’t refuse to participate but believes that if the terminal illness is cancer, it might be more appropriate for an oncologist to do so.

“This is soul searching,” he said. “Doctors will have to decide, now that this is here, what do they do when a patient is terminal and there is nothing more for them?”

The California Academy of Family Physicians is putting information for members on its website and producing podcasts that feature family physicians sharing patient stories and explaining the need for good end-of-life care.

Fairchild holds a cell phone cover he found online. He became an advocate for melanoma awareness since being diagnosed with the cancer. (Heidi de Marco/KHN)

Jay Lee, president of the association, said there is still a lot of uncertainty about the implications for physicians. But he said they will play an important role in helping ensure there is equitable access to the law across ethnic and socioeconomic groups in California — and that patients understand all their choices, including hospice and palliative care.

Lee, a family physician in Orange County, said he believes the law is already leading to more conversations about the end-of-life in general.

“The law has triggered a lot of focus on an area of health care that for many was really taboo,” Lee said. “Physicians didn’t feel really comfortable bringing it up.”

Matt Fairchild said he plans to talk soon with his oncologist about the aid-in-dying law. “I want to make sure he knows that it is there,” he said.

Fairchild was diagnosed with cancer in 2012 after noticing a mole under his earlobe had gotten bigger. He had surgery and thought he was clear, but soon after, doctors told him the cancer had spread to his lymph nodes – and then throughout his body.

For nearly four years, Fairchild has undergone treatment, including radiation, chemotherapy and immunotherapy. Sometimes he feels like he is in a game of Whack-A-Mole, trying to beat it down in one site before it pops up in another. He knows the treatments can only lengthen his life – not save it.

Before the law passed, Fairchild said he would have considered taking his own life if he were dying and in too much pain. But he said, that’s a “quiet, cold way to die.” Now with the new law, he said he hopes that death will be more celebratory and peaceful.

“I don’t want to hurt ever,” he said. “I can’t fathom the idea of being in pain and not having a way out.”

Fairchild, whose face is pale and stomach swollen, spends his days at the apartment he shares with his wife. A calendar hangs from the kitchen wall, with his appointments for brain scans and blood tests and infusions scribbled in small squares.

On a recent afternoon, his cats purring nearby, Fairchild sat down on a recliner chair in front of the television. He pulled out pens and a grown-up coloring book. The title: Color Me Calm.

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.