After four people were murdered in one week in early September — all in the same Washington, D.C., neighborhood — residents made a plea for help.

“We’ve been at funerals all week,” said Janeese Lewis George, a City Council member who represents the neighborhood. “What can we do as a community?”

She was speaking to dozens of people at a vigil site, a tree adorned with teddy bears and candles along a street lined with rowhouses. According to police, the area, known as Brightwood Park, has been plagued by several dozen violent, gun-related crimes over the past year. When Lewis George asked whether the crowd had known anyone who’d been shot, most people raised their hands.

Earlier that day, five council members joined Lewis George in asking Mayor Muriel Bowser for assistance — not in the form of more police, but from the city’s first-ever gun violence prevention director, Linda Harllee Harper.

Harllee Harper knows Brightwood Park, having grown up near the heavily Black and Latino neighborhood, which has recently begun to attract white residents, too. She knows the local stories, both good and bad. Some families have lived there for decades, witnessing generational poverty and government neglect. During the 1990s, parts of it were considered a “war zone” because of rampant drug- and gang-related activity. She still lives in the same ward with her husband and son, who plays basketball at the local recreation center with the children of a recent murder victim.

Her investment in finding a solution is clear. “It’s not a new development,” Harllee Harper told KHN. “My view of gun violence is shaped by how much loss I’ve experienced. I’ve had friends who have been killed and I also have had young people that I have worked with be killed.”

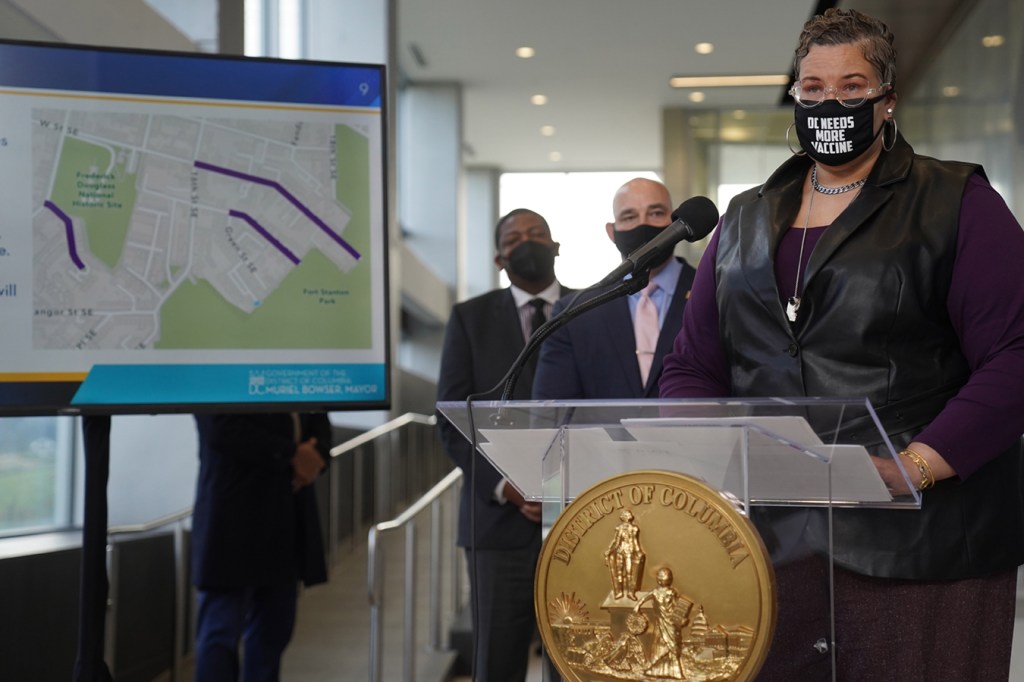

D.C. began 2021 with two crises: the coronavirus pandemic and a gun violence epidemic. To respond to the latter, Bowser advanced plans to draw on lessons learned from the former. She started by creating a position, one that anti-gun violence groups had long requested and became too urgent to ignore: gun violence prevention director. Enter Harllee Harper, who was appointed Jan. 28.

About three weeks later, the mayor declared a public health emergency over gun violence and created an “emergency operations center” that mirrored the city’s covid-19 response. No part of the U.S. has been spared from an increase in murders during the pandemic. And in the nation’s capital the murder toll is outpacing last year’s, which reached 198, a 16-year high. Per capita, that’s about 29 murders per 100,000 residents.

The City Council has directed unprecedented funding to support the efforts.

Harllee Harper, 56, started her 20-plus-year career at D.C. Public Schools as a substance abuse prevention and intervention coordinator. Most recently, she was senior deputy director for the D.C. Department of Youth Rehabilitation Services, where she helped overhaul the agency.

“I’ve run programs before, but this was a different level of limelight” than something she would have signed up for on her own, she said.

Nine months into this new role, Harllee Harper’s most powerful tool is the mayor’s initiative, Building Blocks. Drawing on public health strategies to contain the spread of gun violence, it’s designed to treat the immediate symptoms and root causes of community violence.

Its workers operate almost as contact tracers, whose methods have become familiar during the pandemic. They enter targeted communities to form relationships and connect high-risk residents to violence interrupters, who are trained to de-escalate conflict. They also arrange for resources, like drug addiction treatment and housing assistance. The idea is to reach the small number of people who engage in dangerous behavior and invest in them and their neighborhood.

“Hopelessness combined with a gun, combined with substance abuse, is a really bad combination. And I think that’s what we are seeing right now,” said Harllee Harper.

Building Blocks is up and running in about a third of its targeted 151 blocks — 2% of the city — that were connected to 41% of last year’s gunshot-related crimes last year. (Brightwood Park is not on this list but is included in the city’s fall crime prevention initiative run by the police department.)

These diverse neighborhoods are home to people who tend to be poorer and lack access to resources and opportunities. Statistics among covid and murder victims look similar: The same neighborhoods were hit hardest and the vast majority of deaths have befallen Black people.

D.C. stemmed the spread of covid far more efficiently than the nation as a whole, in part through government action. The city’s crash course on public health during the pandemic could mean it’s better situated to address gun violence. “We can explain certain things through this public health lens and people can understand it a bit better,” said David Muhammad, executive director of the National Institute for Criminal Justice Reform.

He said D.C.’s approach is unique and Harllee Harper’s position is rare. “If you claim to want to reduce gun violence in your city, prove it. Whose full-time job is it in your city to do that? In most cities, it is zero,” he said. “Don’t tell me the police chief. That’s a small portion of their job.”

For the few dozen cities that have some sort of anti-violence czar, the position is relatively new. Richmond, California, is an exception, with an agency dedicated to reducing gun violence since 2008. Richmond’s Office of Neighborhood Safety has been heralded as a model. By 2013, Richmond went from more than 40 homicides a year to 16, according to Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence — its lowest number in three decades.

Harllee Harper’s position is housed not within the public safety agency but the city administrator’s office, presumably affording her more authority and oversight of government programs.

And Building Blocks created a mobile app with which its employees can flag requests during walk-throughs of select neighborhoods. An employee could make a request using the city’s “311” service line to repair a streetlight that is out, for example, and the agency responsible would prioritize it because it came from Building Blocks.

There’s no guarantee these interventions will work, though multiple studies have shown positive outcomes of violence interrupters or infrastructure improvements, such as cleaning and transforming vacant lots and abandoned buildings.

But Daniel Webster, director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Prevention and Policy in Baltimore, said it’s important to track successes and failures because efforts like the one Harllee Harper is spearheading don’t “always work in all places” and there are lessons to learn when they don’t.

“We can’t expect the workers to just perform miracles,” said Webster.

While expectations are high, Harllee Harper’s success depends on whether government and business leaders will respond with the same urgency as they did when the health director requested action.

“The biggest hurdle really is getting all of government to buy into a new day and a new way to get things done,” said council member Charles Allen, who chairs a committee that created Harllee Harper’s position. “Bureaucracy is not nimble.”

“My colleagues in the sister agencies across the city, when Building Blocks calls, they are very, very responsive,” said Harllee Harper. “We’re working together to create performance metrics for agencies related to gun violence prevention.”

Some residents remain skeptical. Residents of the first Building Blocks neighborhood said the follow-up continues to lag. Jamila White, an elected member of the Advisory Neighborhood Commission, said she had several conversations with Harllee Harper and gave her a tour to point out the needs, including quick fixes like adding or fixing streetlights and regular street-sweeping. White has yet to see expedited results, she said, but respects Harllee Harper and admits that no one could address all the issues, many rooted in poverty, alone.

“There’s a lot of shared agreement. But you know, having a shared agreement and having political will and power to do something is a different thing,” said White.

This story was produced by KHN (Kaiser Health News), a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.