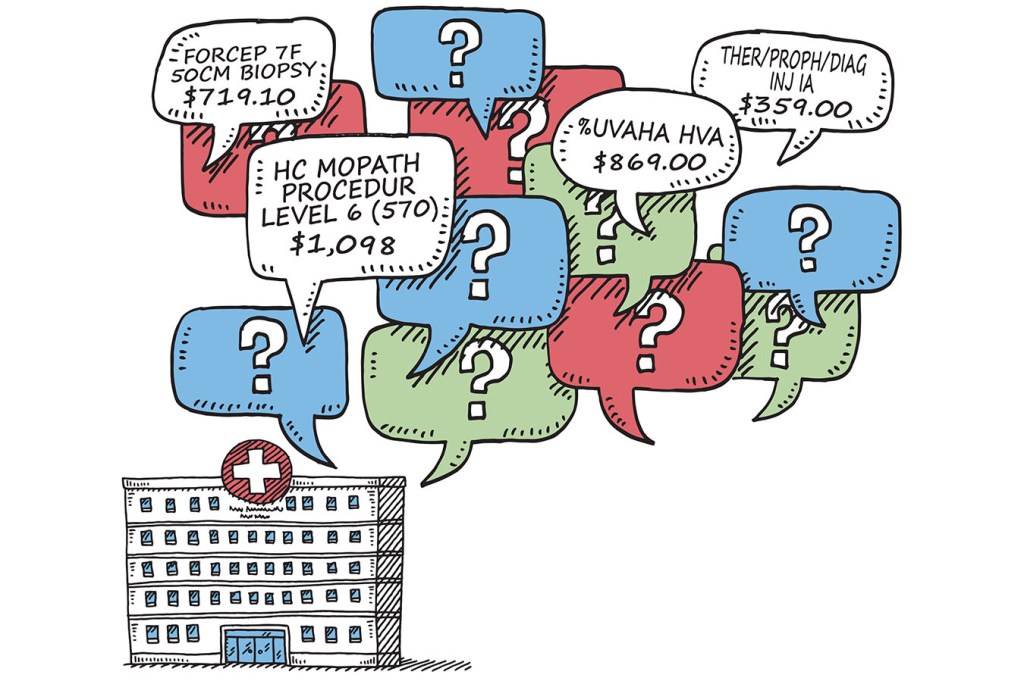

As of Jan. 1, in the name of transparency, the Trump administration required that all hospitals post their list prices online. But what is popping up on medical center websites is a dog’s breakfast of medical codes, abbreviations and dollar signs — in little discernible order — that may initially serve to confuse more than illuminate.

Anyone who has ever tried to find out in advance how much a hospital test, procedure or stay will cost knows the frustration: “Nope, can’t tell you” or “It depends” are common replies from insurers and medical centers.

While more information is always welcome, the new data will fall short of providing most consumers with usable insight.

That’s because the price lists displayed this week, called chargemasters, are massive compendiums of the prices set by each hospital for every service or drug a patient might encounter. To figure out what, for example, a trip to the emergency room might cost, a patient would have to locate and piece together the price for each component of their visit — the particular blood tests, the particular medicines dispensed, the facility fee and the physician’s charge, and more.

“I don’t think it’s very helpful,” said Gerard Anderson, director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Hospital Finance and Management. “There are about 30,000 different items on a chargemaster file. As a patient, you don’t know which ones you will use.”

And there’s this: Other than the uninsured and people who are out-of-network, few actually pay full charges.

The requirement to post charges online in a machine-readable format, such as a Microsoft Excel file, came in a 2018 guidance from the Trump administration that builds on rules in the Affordable Care Act. Hospitals have some leeway in deciding how to present the information — and currently there is no penalty for failing to post.

“This is a small step” toward price transparency amid other ongoing efforts, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Administrator Seema Verma said in a speech in July.

But finding the chargemaster information on a hospital’s website takes diligence. Patients can try typing the hospital’s name into a search engine, along with the keywords “billing” or “chargemaster.” That might produce a link.

Even when consumers do locate the lists, they might be stymied by seemingly incomprehensible abbreviations.

The University of California San Francisco Medical Center’s chargemaster, for example, includes a $378 charge for “Arthrocentesis Aspir&/Inj Small Jt/Bursa w/o Us,” which is basically draining fluid from the knee.

At Sentara in Hampton Roads, Va., there’s a $307 charge for something described as a LAY CLOS HND/FT=<2.5CM. What? Turns out that is the charge for a small suture in surgery.

Which services, treatments, drugs or procedures a patient will face in a hospital stay is often unknowable. And the charge listed is just one component of a total bill. Put simply, an MRI scan of the abdomen has related costs, such as the charge for the radiologist who reads the exam.

Even something as seemingly straightforward as an uncomplicated childbirth can’t easily be calculated by looking at the list.

Comparisons between hospitals for the same care can also be difficult.

An uncomplicated vaginal delivery charge at the Cleveland Clinic’s main campus is $3,466.

Looking for that same information on the Minnesota Mayo Clinic’s online chargemaster page shows two listings, one for $3,030, described as “labor and delivery level 1 short” and the other for $5,236, described as “labor and delivery level 2 long.” But, what’s a short labor? What’s a long one? How is a patient who didn’t go to med school supposed to know the difference?

Also, those are just the charges for the actual delivery. There are also per-day room charges for mom and the newborn, not to mention additional charges for medications, physicians and other treatments.

To get at the total estimated charge, California requires hospitals to report charges for a select number of such “bundles” of care, called “diagnosis-related groups,” or DRGs, in Medicare jargon.

At the University of California-San Francisco’s hospital, for example, there are two chargemaster line items for vaginal childbirth: One is $5,497 and the other is $12,632. But there’s no indication how these differ. Consumers might then turn to the “bundled” cost based on those DRGs, where the ancillary costs are included. That lists the total charge for an uncomplicated childbirth at an astounding $53,184.

A UCSF spokeswoman said no officials were available to comment on this figure.

Though chargemaster rates are quite different from the lower, negotiated rates that insurers pay, they do become the basis for what patients pay who are without insurance or who are treated at hospitals outside their insurer’s network. Out-of-network patients are often surprised when they get what are called “balance bills” for the difference between what their insurer pays toward their care and those full charges.

Still, even knowing chargemaster rates “would be entirely unhelpful” in fighting a high balance bill, said Barak Richman, a law professor at Duke University who has written extensively about balance bills and hospital charges.

“Chargemasters are enormous spreadsheets with incredibly complicated codes that no one short of a billing expert would be able to make sense of,” he said.

Nevertheless, some experts say that merely making the charges public shines a light on the often very high — and widely varying — prices set by facilities.

Even if those charges are only “what hospitals would like to receive,” posting them publicly could make hospitals “totally embarrassed by the prices,” said Anderson at Hopkins.

Billing expert George Nation, a finance professor at Lehigh University, said that rather than posting chargemaster lists, hospitals should be required to provide the average prices they accept from insurers. Hospitals generally would oppose that, saying negotiated rates are a trade secret.

It’s unclear that the lists will have much impact. “It’s been the norm here in California for over a decade,” said Jan Emerson-Shea, vice president of external affairs for the California Hospital Association. Even so, “from a practical standpoint, I’m not sure how useful this information is,” she said. “What an individual pays to [the] hospital is going to be based on what their insurer covers.”

That could include such things as the annual deductible, whether the facility or physicians involved in the care are in-network and other details.

“The hospital piece is just a small piece,” said Ariel Levin, senior associate director for state issues at the American Hospital Association.

Still, “the biggest concern is it falls short of that end goal because it really doesn’t help consumers understand what they are going to be liable for,” she said.

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.