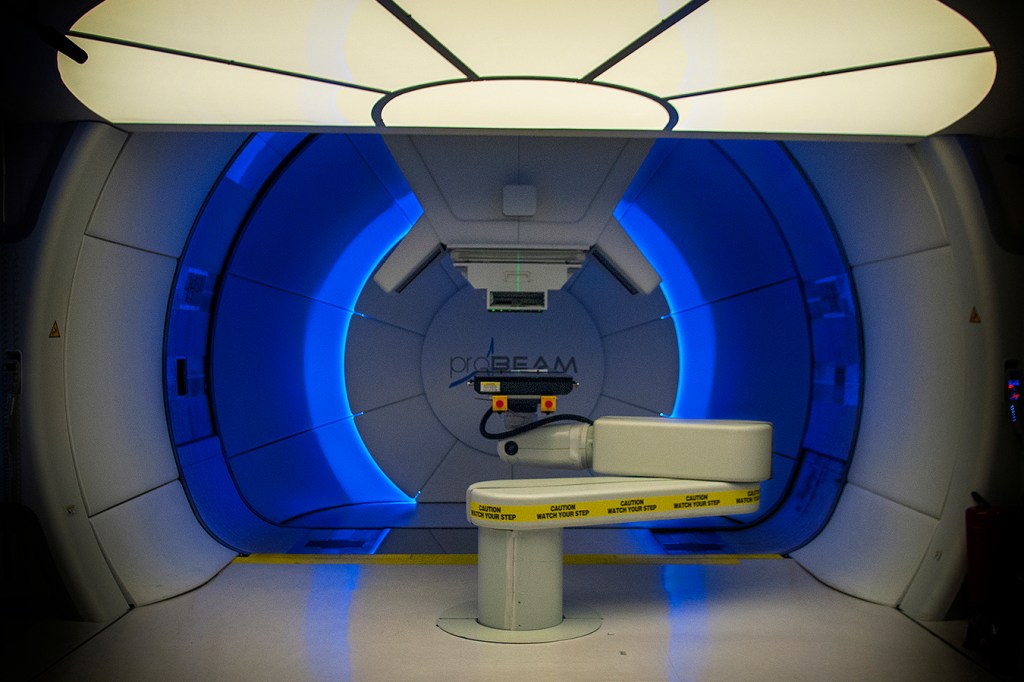

WASHINGTON — On March 29, MedStar Georgetown University Hospital opened a proton-therapy cancer unit that is expected to treat about 300 patients a year at premium prices using what its proponents promote as the most advanced radiology for attacking certain tumors.

At the facility’s heart is a 15-ton particle accelerator that bombards malignancies with beams of magnet-controlled, positively charged protons designed to stop at tumors rather than shoot through them like standard X-ray waves, mostly sparing healthy tissue.

With the addition, Georgetown joined a medical arms race in which hospitals and private investors, sometimes as partners, are pumping vast sums of money into technology whose effectiveness, in many cases, has not yet been shown to justify its cost.

Although most of the proton centers in the United States are profitable, the industry is littered with financial failure.

One of the most recent examples is the California Protons Cancer Therapy Center in San Diego, which filed for bankruptcy protection last year. Formerly associated with Scripps Health, the center opened in 2014 but attracted only a fraction of the 2,000 patients per year it planned to treat, according to Modern Healthcare.

Renamed California Protons in December, the center has obtained new financing and is expanding relations with the UC San Diego Health System and Rady Children’s Hospital in the hope of increased patient volume.

The first hospital-based proton center opened at Loma Linda University Medical Center, in 1990. Officials there speculated that it would prove a “milestone” in treating cancer.

“This is an important beginning,” Dr. James Slater, chairman of Loma Linda’s department of radiation medicine, told the Los Angeles Times back then. “If this [treatment] produces the benefits we anticipate, there will be many, many centers like this one available to cancer patients.”

Now, about 30 years after the Food and Drug Administration first approved proton therapy for limited uses, nearly a third of the existing proton centers lose money, have defaulted on debt or have had to overhaul their finances, documents and interviews with executives show. Doctors often hesitate to prescribe the therapy and insurers often will not cover it.

For Georgetown officials, it was still a bet worth making.

“Every major cancer center that has a full-service radiation oncology department should consider having protons,” said Dr. Anatoly Dritschilo, the chief of the hospital’s radiation medicine department.

Many have. There are 27 proton-therapy facilities now operating in the United States. Nearly as many are being built or planned. Georgetown’s, which vies for patients with a struggling unit in Baltimore, will soon compete with another in Washington and one in Northern Virginia.

But there simply may not be enough business to go around.

“The biggest problem these guys have is extra capacity,” said Dr. Peter Johnstone, the chief executive at Indiana University’s proton center before it closed in 2014, in need of an upgrade but lacking the potential patients to pay for it. “They don’t have enough patients to fill the rooms.”

(Story continues below.)

At Indiana, he added, “We began to see that simply having a proton center didn’t mean people would come.”

Proton therapy was initially used to treat tumors in delicate areas where surgery was not an option — near the eye, for example — and in children, and it remains the best choice in such cases.

But its pinpoint precision has not been shown to be more effective against breast, prostate and other common cancers. One recent study of lung-cancer patients found no significant difference in outcomes between people receiving proton therapy and those getting a focused kind of traditional radiation, which is much less expensive. Other studies are still underway.

“Commercial insurers are just not reimbursing” for proton therapy except for pediatric cancers or tumors near sensitive organs, substantially limiting the potential treatment pool, said Brandon Henry, a medical device analyst for RBC Capital Markets.

Medicare covers proton therapy more readily than private insurers, but relying solely on Medicare patients does not allow backers of some treatment centers to recoup their investments, much less turn a profit, analysts said.

For another glimpse of what can go wrong, consider the Maryland Proton Treatment Center in Baltimore, which is affiliated with the University of Maryland Medical Center.

Opened two years ago with a “Survivor”-themed party and lofty financial goals, the unit is already undergoing a restructuring that is inflicting large losses on its outside investors, including wealthy families from Texas.

Before the Baltimore center opened, those behind it saw their market stretching from Philadelphia to Northern Virginia and encompassing 20,000 potential patients a year. Officials predicted the unit would treat “north” of its current rate of about 85 patients a day, said Jason Pappas, the acting chief executive.

How far north?

“Upper Canada,” said Pappas, declining to provide hard numbers. He said the center would break even by the end of the year.

The patient shortage might not be a good sign for projects in the pipeline, but it is encouraging for those who take a dim view of proton therapy’s rise.

“Something that gets you the same clinical outcomes at a higher price is called inefficient,” said Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel, a health policy professor at the University of Pennsylvania, which operates one proton center and is developing another. “If investors have tried to make money off the inefficiency, I don’t think we should be upset that they’re losing money on it.”

Despite the early foray by Loma Linda in California, the proton-therapy boom effectively began in 2001, when Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston opened a proton unit. By 2009, developers were flocking to the field, lured by the belief that insurers would cover treatment bills that run to $48,000 and more.

The treatment held particular promise for prostate cancer patients, given the potential side effects, including incontinence and impotence, associated with traditional radiation.

But a 2013 Yale study found little difference in those conditions among patients getting proton therapy versus those getting traditional radiation. Within a year, several insurers stopped covering the therapy for prostate cancer or were reconsidering it.

Indiana University’s center was the first to close. Before long, others were in dire financial straits.

An abandoned proton project in Dallas, developed by the same investors who launched the San Diego and Baltimore facilities, is in bankruptcy as well.

In Virginia, the Hampton University Proton Therapy Institute has lost money for at least five straight years, financial statements show. In Knoxville, Tenn., the Provision CARES Proton Therapy Center lost $1.7 million last year on revenue of $23 million, $5 million short of its target.

Centers in Somerset, N.J., and Oklahoma City run by privately held ProCure have defaulted on their debts. According to the investment firm Loop Capital, a center associated with Seattle Cancer Care Alliance, a hospital consortium, in Washington state lost $19 million in fiscal 2015 before restructuring its debt, documents show. A center near Chicago lost tens of millions of dollars before its own restructuring as part of a 2013 sale to hospitals now affiliated with Northwestern Medicine, according to regulatory documents.

Scott Warwick, executive director of the National Association for Proton Therapy, a trade group, blames “over-exuberant expectations” for the problems.

“I think maybe that’s what went on with some of the centers,” he said. “They thought the technology would grow faster than it has.”

In advertising and marketing, some centers go to lengths to distinguish themselves from the competition.

“Since 1990, Loma Linda University Medical Center’s Proton Treatment Center has been leading the way in effective, cutting-edge prostate cancer treatment with protons,” the California hospital’s website reads. “Simply put: we have treated the most patients with proton therapy and have the most experienced staff in the world.”

The industry also is urging patients and lawmakers to press insurers to pay for proton therapy.

Oklahoma recently passed a law requiring that insurers evaluate the treatment on an equal basis with other therapies. Virginia has considered similar legislation. At the National Proton Conference in Orlando last year, a full day was devoted to winning over insurers. The Alliance for Proton Therapy Access, another industry group, has software for generating letters to the editor demanding coverage.

Until the insurance outlook changes, those developing new proton centers have scaled back their ambitions. Georgetown’s unit, for example, cost $40 million and has a single treatment room. The one in Baltimore cost $200 million and has five.

Following the Georgetown model, with one or two treatment rooms, should allow centers in major metropolitan areas to make money, said Prakash Ramani, a senior vice president at Loop Capital, which is involved with projects in Alabama, Florida and elsewhere.

Not all the new units are small. In some cases, hospitals are joining forces to make the finances work. In New York, Memorial Sloan Kettering, Mount Sinai and Montefiore Health System have teamed up on a $300 million unit with an 80-ton particle accelerator and four treatment rooms that is set to open in East Harlem next year.

Officials, counting on the New York area’s vast population and referrals from three major health systems, expect the center to treat 1,400 people a year. They will soon learn whether they can fare better than the Indiana proton center did.

“What places need now are patients,” Johnstone, that center’s former chief, said, “a huge supply of patients.”

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.