California’s health care industry has a consolidation problem.

Independent physician practices, outpatient clinics and hospitals are merging or getting gobbled up by private equity firms or large health care systems. A single company can dominate an entire community, and in some cases, vast swaths of the state.

Such dominance can inflate prices, and consumers end up facing higher insurance premiums, more expensive outpatient services and bigger out-of-pocket costs to see specialists.

Now that COVID-19 has slammed the health care industry, especially the small practices that are barely seeing patients, the trend is likely to accelerate.

“I don’t see anything that’s going to stop this wave of consolidations amongst docs,” said Glenn Melnick, a health care economist at the University of Southern California.

“If this thing goes on a long time,” he said of the coronavirus, “then it becomes a tsunami.”

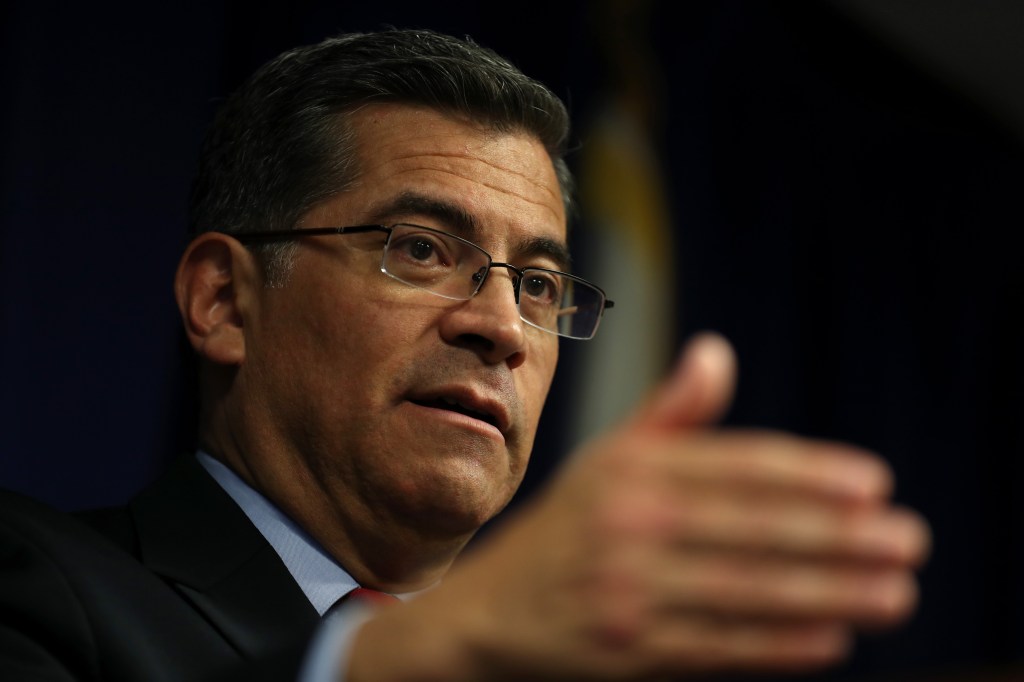

California Attorney General Xavier Becerra has made battling health care consolidation a signature issue since he took office in 2017. With the additional pressure that COVID-19 is putting on vulnerable practices and facilities, Becerra is now pressing the state legislature to expand his authority to slow health care mergers.

“We find that in these times of crisis, economic and health crisis, that the smaller health care players and stakeholders are oftentimes most at risk of being swallowed up by the big fish,” Becerra told California Healthline.

His success would fundamentally change how the health care industry merges and grows in California.

When a health care system, private equity firm or hedge fund plans to merge with or acquire another practice or facility — whether that means buying a small practice or joining a multistate hospital chain — Becerra wants to know about it. He wants written notice, and the ability to deny any sale that doesn’t deliver better access, cost or quality health care to Californians.

Becerra already can regulate mergers among nonprofit health care facilities. Under SB-977, a collaboration between Becerra’s office and the legislature, he would get the ability to regulate the for-profit sector as well.

“Certainly it would put California where it’s accustomed to being,” Becerra said. “At the head of the pack.”

The bill has support from organized labor and consumer advocacy groups. Gov. Gavin Newsom has come out against health care consolidation in the past but hasn’t taken an official stance on the bill.

Yet Becerra isn’t convinced passage will be smooth.

“The biggest concern I have is the legislation will be killed by the industry,” he said. “We’ll end up seeing over-consolidation because decent practices that got on the edge could not swim with sharks.”

Indeed, health care industry players are already lining up against the bill. Alex Hawthorne, a lobbyist for the California Hospital Association, said that hospitals are stretched thin because of the pandemic, and that now isn’t the time for Becerra to be meddling in routine agreements between practices.

“It bestows absolute and arbitrary discretion on the office of the attorney general,” Hawthorne said at a budget hearing in May.

In 2010, about 25% of California physicians worked in a practice owned by a hospital. By 2016, more than 40% of doctors worked in hospital-owned practices, according to research published in the journal Health Affairs in 2018.

There’s evidence that consolidation can hurt consumers. A separate 2018 study found that the cost of medical procedures in highly consolidated Northern California was 20% to 30% higher than in Southern California.

Since 2018, California’s attorney general has had the authority to regulate mergers among nonprofit health care systems, which Becerra exercised the same year when considering a merger between two health care giants: Dignity Health and Catholic Health Initiatives. He said he would approve the deal only if the systems agreed to certain requirements, such as starting a homelessness program.

Later that year, Becerra joined a suit against Sutter Health for using its market power to drive up health care costs in Northern California.

The lawsuit alleged that Sutter, which has 24 hospitals and 34 surgery centers, had spent years buying up practices and facilities, giving insurers little choice but to include them in their networks and agree to higher rates for services.

In October 2019, Becerra secured a $575 million settlement against Sutter, which has yet to be finalized or paid out, that requires Sutter to change how it charges insurance companies and give patients more information about prices.

Sutter Health opposes SB-977, which was introduced in February by state Sen. Bill Monning (D-Carmel). The measure is intended to address some of the challenges Becerra encountered with the Sutter case, Becerra said.

“The best way to prevent problems from occurring in a merger is just to prevent the merger altogether,” said Jaime King, associate dean at UC Hastings College of the Law in San Francisco. “It’s really hard to unwind a merger after you’ve already done it.”

Under the measure, the attorney general must be notified before a system, hedge fund or private equity firm attempts to enter into a merger, acquisition or another kind of affiliation change with another practice or facility. The bill defines a health care system as one with two or more hospitals in multiple counties, or three or more hospitals within one county.

That would trigger a public review process allowing supporters and opponents to make their cases to a review board. The board would assess the transaction, using criteria to determine whether it would improve access, quality and price.

The bill also would make it illegal for systems to act anti-competitively and give the attorney general the power to bring a civil suit against monopolistic systems.

The Senate Health Committee approved the bill, which is expected to be heard in another committee this week.

“Maybe it does mean consolidation should occur, but only because we’ve done the oversight to make sure it’s because of quality and access,” Becerra said. “Not because a big fish wants to make bigger profit.”

The measure includes waivers for rural practices and a fast-track review process for transactions under $500,000.

The California Chamber of Commerce opposes the bill, as does the California Medical Association, which represents doctors. While the California Medical Association is concerned about the survival of small physician practices, it believes the bill is too broad and should focus more tightly on hospital consolidation, said spokesperson Anthony York.

“This approach will only further force smaller providers out of business,” especially as the health systems respond to the COVID-19 emergency, the group’s legislative advocate, Amy Durbin, wrote in a letter of opposition.

For many independent practices struggling for survival, the debate over Becerra’s powers is academic.

Dr. Sarah Azad, who owns a women’s health practice in Mountain View, California, said at least three independent practices in her area have started the process to merge or sell since March because of dramatically lower patient volume.

Her practice is fine for now, despite the fact that her patient volume was only about 30% of normal in March and 60% of normal in April. Azad received a loan from the federal Paycheck Protection Program for small businesses so she could pay her five doctors in May.

“If you catch me on a bad month, I feel like we’re one disaster away from bankruptcy,” Azad said.