[UPDATED at 12:15 p.m. PT]

Joseph Daskalakis’ son was born New Year’s Eve, a little over a week into the current government shutdown, and about 10 weeks before he was expected.

Little Oliver ended up in a specialized neonatal intensive care unit, the only one that could care for him near their home in Lakeville, Minn.

But air traffic controller Daskalakis, 33, has an additional worry: The hospital where the newborn is being treated is not part of his current insurer’s network and the partial government shutdown prevents him from filing the paperwork necessary to switch insurers, as he would otherwise be allowed to do. He could be on the hook for a hefty bill — while not receiving pay. Daskalakis is just one example of federal employees for whom being unable to make changes to their health plans really matters.

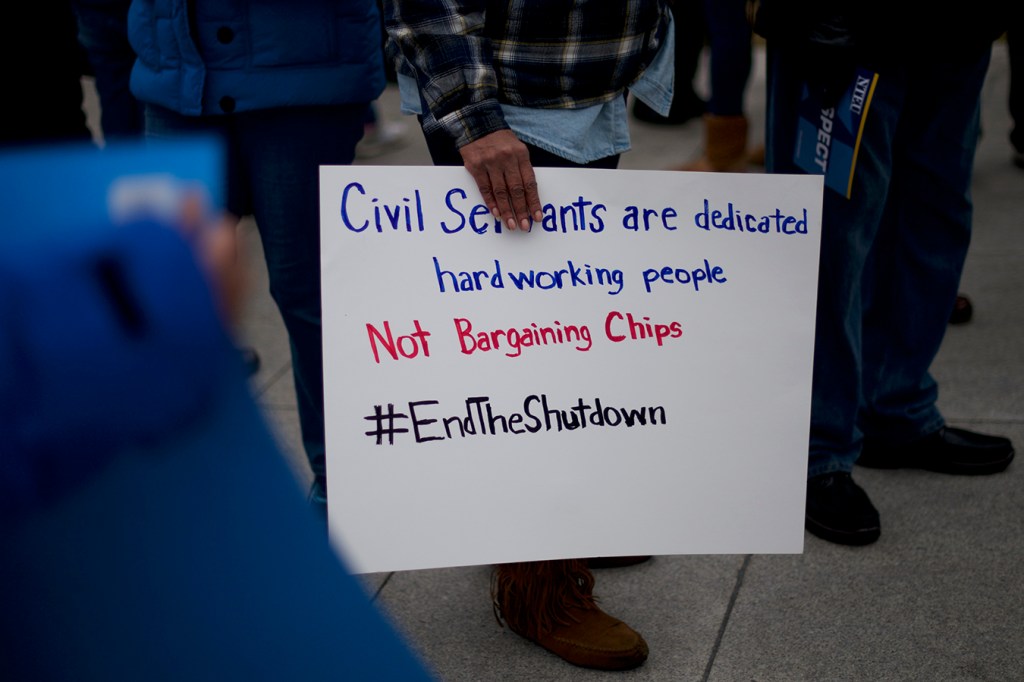

Although the estimated 800,000 government workers affected by the shutdown won’t lose their health insurance, an unknown number are in limbo, like Daskalakis, unable to change insurers because of unforeseen circumstances; add family members such as spouses, newborns or adopted children to an existing health plan; or deal with other issues that might arise.

“With 800,000 employees out there, I imagine that this is not a one-off event,” said Dan Blair, who served as both acting director and deputy director of the federal Office of Personnel Management (OPM) during the early 2000s and is now senior counselor at the Bipartisan Policy Center. “The longer this goes on, the more we will see these types of occurrences.”

While Oliver is getting stronger every day — he’s now out of the ICU, according to Daskalakis’ local air traffic union representative — it’s unclear how the situation will affect his family’s finances.

That’s because out-of-network charges are generally far higher than being in-network, and NICU care is enormously expensive no matter what. Those bills could add up, especially as his current insurance has an out-of-pocket maximum of $12,000 annually. Because Oliver was born before the new year, the family could face that amount for 2018 — and 2019.

Daskalakis isn’t getting paid, either.

“I don’t know when I’ll be able to change my insurance, or when I’ll get paid again,” Daskalakis wrote Sen. Tina Smith (D-Minn.), who shared his letter on Facebook and before the Senate last week.

Other families are also worried about paperwork delays, and the financial and medical effects a prolonged shutdown could cause.

Dania Palanker, a health policy researcher at Georgetown’s Center on Health Insurance Reforms, studies what happens when families face insurance difficulties. Now she’s also living it.

After arranging to reduce her work hours because of health problems, Palanker knew her family would not qualify for coverage through her university job. No problem, she thought, as she began the process in December to enroll her family into coverage offered by her husband’s job with the federal government.

“We could not get the paperwork in time to apply for special enrollment through the government and get it processed before the shutdown,” Palanker said.

Georgetown allowed her to boost her work hours this month to keep the family insured through January, but Georgetown’s share of her coverage will end in February.

Her treatments are expensive, so she is likely to hit or exceed her annual $2,000 deductible in January — then start over with another annual deductible once the family secures new coverage.

“I’m postponing treatment in hopes that it is just a month and I’m back on the federal plan in February, but I can’t postpone indefinitely, as my condition will get worse,” said Palanker, who has an autoimmune disease that causes nerve damage.

Overseeing federal health benefits programs is within the purview of the OPM, whose data hub is operational, according to a spokeswoman. But getting information to that data hub to make the kind of changes Daskalakis, Palanker and others need depends on the individual agencies that employ government workers.

The OPM has told government agencies “that they should have HR staff available during the lapse, specifically to process” such requests, which are called “qualifying life events,” the spokeswoman said.

Workers enrolled in plans under the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association, which covers about 5 million federal workers and retirees in the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program, can make qualifying life event changes directly with the insurer if they can’t get it processed by their workplace, an association spokesman said on Friday.

In a written statement Wednesday, Smith said: “Oliver’s story is a powerful reminder that hundreds of thousands of real families have had their financial and personal lives turned upside down by this unnecessary shutdown.” She called on the president to come back to the negotiating table.

For Daskalakis, there is some good news.

Tony Walsh, his union rep, said the OPM website and Daskalakis’ insurer both indicated that the air traffic controller’s request to change carriers so the hospital will be in-network will be retroactive to Oliver’s birthday, and the out-of-network charges may not play a role.

Just to be safe, “Joe is currently working on an insurance appeal based on no in-network care [being available],” Walsh said in an emailed statement. The family has already received an initial $6,000 bill from the hospital, Walsh noted, saying the charges do not include costs associated with Oliver’s birth or his stay in the intensive care unit.

Walsh said the shutdown is affecting a broad swath of employees in ways many lawmakers had never anticipated.

The workers “are essential to the system, and it’s unfair they are being treated this way,” he said.

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.