Imagine your doctor telling you have Alzheimer’s disease or some other type of dementia. Then, imagine being told, “I’m sorry, there’s nothing we can do. You might want to start getting your affairs in order.”

Time and again, people newly diagnosed with these conditions describe feeling subsequently overcome by hopelessness.

In their new book, “Better Living With Dementia,” Laura Gitlin and Nancy Hodgson — two of the nation’s leading experts on care for people with cognitive impairment — argue forcefully that it’s time for this “cycle of despair” to be broken.

“There is no cure for Alzheimer’s but there are many things that can be done to make life better for people with dementia and their caregivers,” said Gitlin, dean of the College of Nursing and Health Professions at Drexel University and chair of the Department of Health and Human Services advisory council on Alzheimer’s Research, Care and Human Services.

At a minimum, Gitlin and Hodgson suggest pointing people newly diagnosed with dementia to the Alzheimer’s Association, the Lewy Body Dementia Association, the Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration and the government’s website, alzheimers.gov — all valuable sources of information and potential assistance.

Also, individuals and families should obtain referrals to elder law attorneys, financial planners, adult day centers, respite services and caregiver support services, among other resources. But none of this happens routinely. Instead, “people are not given access to the resources they need to plan for the future,” said Hodgson, the Anthony Buividas endowed term chair in gerontology at the University of Pennsylvania. “They’re left on their own to find out even basic information.”

Most people with Alzheimer’s and other types of dementia live at home — an estimated 70 percent. But few professionals inquire about patients’ living conditions, even though these environments play a major role in shaping people’s safety and well-being. (The remainder live in nursing homes or assisted living residences.)

More often than not, professionals don’t help families anticipate what to expect as dementia progresses. Left to their own devices, individuals with dementia and their caregivers “tend to move inwards and away from their communities, which fosters isolation, which worsens their sense of despair,” Hodgson said.

Even small steps could help improve quality of life. In their book and subsequent phone conversations, Gitlin and Hodgson highlighted several strategies:

Attend to the home. As people with dementia become more impaired, attention to their home environment needs to become a priority.

In one study cited in Gitlin and Hodgson’s book, safety issues — cleaning agents under the sink, knives and other sharp objects, guns and ovens that can be turned on and left running, for instance — were discovered in 90 percent of homes where people with dementia lived. Another study found an average of eight hazards in these residences.

What can be done: Hire an occupational therapist, ideally with expertise in dementia, to do a home assessment and recommend modifications.

Common suggestions: Reduce clutter, which can contribute to disorientation. Install handrails along staircases and grab bars and shower seats in bathrooms to reduce the risk of falls. Put up visual cues that identify where common objects are stored — underwear and socks, for instance, or coffee mugs. Make sure lighting is adequate. Remove knobs from stoves and remove other potentially dangerous electronic devices.

“What you want to know is can a person with dementia find their way easily in the home? Are there sufficient cues? Is the environment too stimulating — is there too much noise from a television that’s left on during the day, for example — or not stimulating enough?” Gitlin said.

Create a routine. People with dementia need predictability and well-structured routines that minimize uncertainty and help them get through the day.

“A routine helps people with dementia know what to expect,” Hodgson said. “That lowers their anxiety and stress and makes it easier for them to negotiate their environments. If change is introduced regularly, they’re just not going to do as well.”

What can be done: Time activities through the day to match an individual’s physical and psychological rhythms.

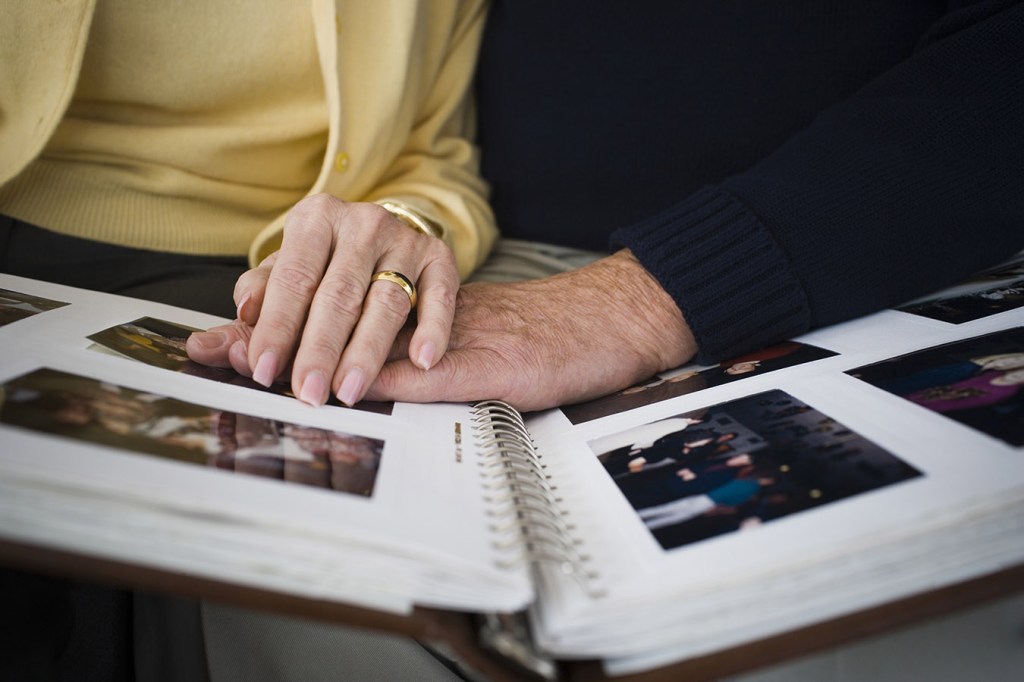

Common suggestions: Most people are sharper, cognitively, in the morning, so that’s a good time to look through photo albums, do puzzles, reminisce about the past, play simple word games or go off to adult day care, Hodgson said.

After lunch, people may need to rest, but they shouldn’t nap too long. “You want to have some physical activity in the afternoon, as more and more research is showing the importance of exercise for people with dementia,” Hodgson noted.

Around sunset, it’s time for relaxation and helping people settle down. Playing music or lighting a scented candle can set the mood. Good sleep hygiene — no caffeine at the end of the day, darkness, quiet and comfortable temperatures in the bedroom — is recommended at night, as sleep problems are common in people with dementia.

An occupational therapist, who can evaluate the skills of people with dementia, can suggest appropriate activities. “You’ll need to learn how to understand if someone can initiate an activity on their own or follow a sequence needed for the activity,” Gitlin said. “If not, and this is common later on, you’ll have to learn how to set up the activity and cue the person.”

Know what to expect. Individuals with dementia and their caregivers will find their needs changing as their illness progresses.

What can be done: During every significant transition, reassess needs and how you’re going to get them met — with the help of an experienced social worker or care manager, if possible. “Who are the people who can help you? What resources are available? What alterations need to be made in the home and care arrangements? You’ll need a new plan of action,” Hodgson said.

At first, the most significant need may be obtaining a reliable diagnosis and learning more about the type of dementia your physician has identified. According to a new study by researchers at Johns Hopkins University, nearly 60 percent of people with dementia have not been diagnosed or are not aware of their diagnosis.

Gitlin and Hodgson recommend that people with dementia be involved in learning about treatment options and planning for their care, to the extent possible. “Talking over people or ignoring them or telling them what should happen, without soliciting their participation, is attack on personhood,” Gitlin said.

Depression and anxiety may need to be addressed, as people struggle with the reality of a diagnosis, withdraw from work or social activities and worry about the future. Finding ways to keep people engaged with meaningful activities starts to become a challenge.

When individuals progress to moderate dementia, they may need more supervision and assistance with dressing, bathing, grooming and taking medications. This is when families often hire caregivers, if they can afford it. Communication may become compromised and problematic behaviors such as wandering, agitation or aggression may emerge.

Often, someone with dementia is unable to express her needs and resorts to difficult behaviors. A person may be bored, afraid, in pain, constipated, overwhelmed or distressed, for example. To cope, caregivers are urged to try to understand the triggers for troublesome behaviors and take steps to address them.

Interactive web-based systems that offer expert assistance to caregivers may become available going forward. Gitlin and colleagues at the University of Michigan and Johns Hopkins University have developed a comprehensive program, WeCareAdvisor, that is being tested. Another website featuring the DICE Approach is expected to debut in three months and include interactive training videos.

In the final stage, severe dementia, people need sensory stimulation — a foot massage, music they enjoy, a fragrant bouquet of flowers. Addressing distress, discomfort and pain are key care challenges. Even if the person with dementia can’t acknowledge it, the presence of family and friends remains important. Throughout every stage of this illness, “it’s important to let people with dementia know that they belong and surround them with a feeling of warmth and affection,” Hodgson said.

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.