A five-state study of Obamacare health insurance exchanges finds California’s to be the “most successful” of the group. Researchers say the state’s experience may provide valuable lessons to lawmakers in Congress seeking to “repeal and replace” the federal health reform law.

California’s exchange, Covered California, has succeeded in large part because of its ability to retain a “relatively large” number of insurers compared with other states, according to the study, sponsored by The Brookings Institution.

Officials also boosted the fortunes of the exchange by aggressively negotiating premiums with insurers and imposing conditions on their participation. And Covered California helped facilitate the enrollment of low-income consumers, the study notes.

Research teams conducting The Brookings study took a deep-dive look at California, Florida, Michigan, North Carolina and Texas to determine what has worked, what hasn’t and why.

“The political process at the moment is not generating a conversation about how do we create a better replacement for the Affordable Care Act,” said Alice Rivlin, senior fellow at The Brookings Institution, who spearheaded the project. “It’s a really hard problem, and people with different points of view about it have got to sit down together and say, ‘How do we make it work?'”

Researchers interviewed public officials, academic experts, health providers, insurers and brokers to try to understand why health plans chose to enter or leave markets, how state regulations affected decision making and how insurance companies built provider networks.

“It turns out the top level talking points from both parties miss what makes insurance exchanges successful,” said Micah Weinberg, president of the Bay Area Council Economic Institute, who led the California research team. “And it doesn’t have anything to do with red and blue states and it doesn’t have anything to do with total government control or free markets.”

Among the key findings:

Health insurance markets are local.

Researchers found insurer competition varied widely not just among the five states, but within them as well.

The most dramatic differences occurred between urban and rural areas ― with the more populated regions generally having more competition among insurers and better-priced plans than rural areas.

Insurance carriers that do business in those rural regions were less able to negotiate prices with the limited number of local hospitals, doctors and other providers.

“Insurance companies don’t make money (in many rural areas) because they can’t cut a deal with the providers that will be attractive to the customers,” Rivlin said. “And there just aren’t very many customers, so it’s not obvious what to do about that.”

Consolidation suppresses competition.

California is no exception. The state’s decision to fully-embrace the federal health law did not insulate it from market variables.

In portions of Los Angeles County, for example, seven insurance carriers offered consumers some of the state’s most affordable policies. By contrast, regions along the central coast and in Northern California provided consumers with only two or three carriers that charged significantly higher-priced plans.

The reason, the researchers found, was the greater degree of consolidation in northern California, where large health systems have bought up physician practices and smaller hospitals, leaving relatively few independent practitioners.

In San Francisco and Contra Costa counties, the phenomenon has reduced provider competition, leaving consumers there with premiums that are much higher on average than in Southern California.

In particular, the study found the lowest priced silver plans sold in those two Bay Area counties cost nearly $150 more than the least expensive silver plans offered in Los Angeles, Riverside and San Bernardino counties.

Provider consolidation is also significant in the state’s rural northern counties, the study found.

Republicans, including the Trump administration, have suggested that the sale of insurance policies across state lines is one way to boost competition. But Rivlin said that misses an important point.

“The insurance companies would still have to have local providers,” she said. “So a company in New York can’t easily sell in Wyoming unless it has providers lined up in Wyoming.”

Underestimating demand from sick people took a toll.

Under Obamacare, insurance companies are prevented from denying coverage to those with preexisting medical conditions. That left insurers, in the early years, uncertain about who would buy coverage through the exchanges and how policies should be priced, the study notes.

As it turned out, an unexpectedly large flood of previously uninsured sick people raced to get coverage when the marketplaces opened.

That caused a number of insurers nationwide to incur losses, with some Florida plans reporting claims that were 50 to 100 percent greater than the premiums they’d collected, the study says.

Making matters worse: A mechanism in the health law to reimburse companies for such losses in the early years proved inadequate, causing a number of them to leave the marketplaces.

In Michigan, six of 16 insurers withdrew. And in regions of Texas and North Carolina, which had between five and nine insurers, only three remained.

But in California only one insurer left the state, leaving 11. The one that exited, in 2016, was UnitedHealthcare ― a newcomer that served only about 1200 enrollees in some rural and coastal regions of the state.

Weinberg said the stability in Covered California was largely due to the state’s decision to require that all policies comply with the Affordable Care Act from day one. By contrast, he said, many other states allowed some consumers to keep their existing, non-compliant plans for up to four years, which kept many healthy ― and thus, less expensive ― consumers out of the exchange.

Many carriers are still doing well ― especially in California.

One lesser-known story about Obamacare is that some carriers are making enough money to reduce their 2017 premiums, according to the study.

In California, while some of the brand-name insurers announced large rate increases, other lesser-known regional health plans lowered their premiums.

“About half the insurers are making a ton of money on [the exchanges], and that’s how markets work,” Weinberg said. “The idea that there should be winners and losers in a particular marketplace is something that Republicans should certainly feel comfortable with.”

Medicaid managed-care plans come out winners

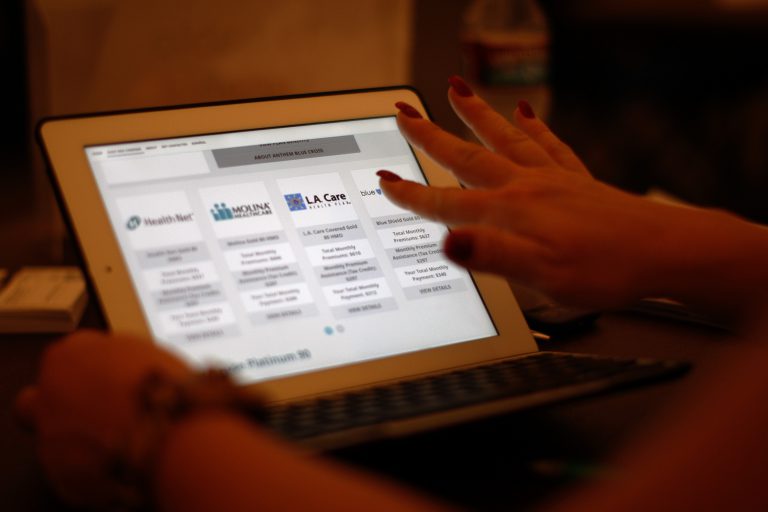

The researchers found that regional insurers which originally went into business to provide coverage for people on Medicaid — health coverage for the poor and disabled known as “Medi-Cal” in California — are selling health plans to non-Medicaid enrollees in many exchanges, filling gaps left by insurers who fled.

Molina Health in California, WellCare in Florida, Community Health Choice in Texas, “appear to have thrived in the ACA marketplace environment,” the study says.

Rivlin said the success of these plans is likely due to several factors, including their experience caring for a low-income, often very sick people and their well-established, narrow networks of local providers.

In California, the well-known commercial brands of insurance initially won about 90 percent of enrollment. But that began to change in 2016. Most notably, researchers pointed to Molina’s success with enrollment, which climbed 350 percent from its 2015 levels.

It’s a trend that, depending upon what happens with Obamacare, may continue, the study says.