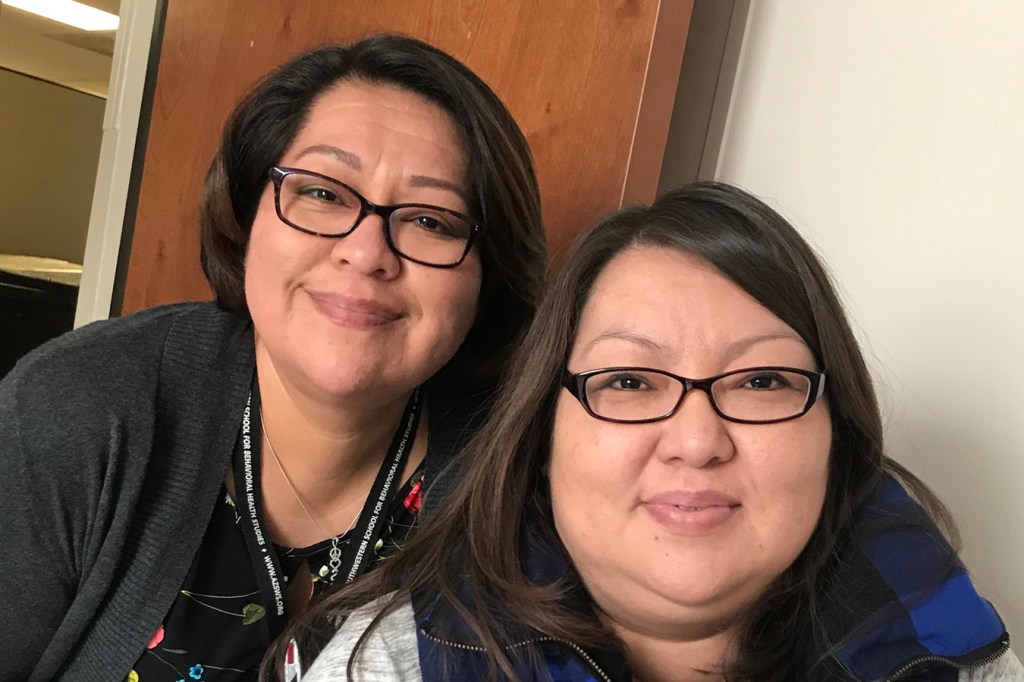

Cheryl and Corrina Thinn were almost joined at the hip. The sisters, both members of the Navajo Nation, shared an office at Arizona’s Tuba City Regional Health Care. Cheryl conducted reviews to make sure patients were receiving adequate care. Corrina was a social worker. Their desks were just inches apart.

They lived together, with their mother, Mary Thinn. They helped raise each other’s children.

And they died just weeks apart, at ages 40 and 44, after falling ill with COVID-19.

Close friend Lynette Goldtooth, a registered nurse and case manager, won’t go near the area of the hospital where they worked, knowing she’ll break down if she sees their empty seats.

“That’s where I used to go to see Corrina every morning,” Goldtooth said. “I used to sit in Cheryl’s chair. Corrina and I would just start talking, catch up on what we did during our time off, laugh and joke.”

Cheryl and Corrina are among hundreds of U.S. health care workers who died after helping patients battle the virus. The Guardian and KHN are investigating more than 1,000 of these workers’ deaths in the Lost on the Frontline project.

Corrina and Cheryl Thinn, two of four siblings, lived together with their mother, Mary, and helped raise each other’s children. From left: Fabian Thinn, Corrina Thinn, Chris Thinn, Mary Thinn and Cheryl Thinn. (The Thinn family)

The Navajo Nation was ravaged by COVID-19 this spring. In May, it reported the highest per capita infection rate in the United States. As of Aug. 21, the sisters were among 489 members of the reservation who had died of the virus, according to the Navajo Department of Health.

Experts attributed the spread to the prevalence of multigenerational housing and poor sanitation infrastructure — many homes lack running water. Like medical centers across the country, local hospitals across the Navajo Nation experienced shortages of personal protective gear.

Corrina Thinn, a licensed social worker, tended to a COVID-19 patient at Arizona’s Tuba City Regional Health Care in early March while not wearing personal protective equipment, according to her sister Chris. (The Thinn family)

In early March, Corrina, without personal protective equipment, saw a patient who was showing symptoms of COVID-19, according to her sister Chris. Corrina made sure the patient was comfortable and asked what else she could do to help. A couple of days later, that patient died, and a test for COVID-19 came back positive.

“Within days after that, she got sick really fast,” Chris said.

The sisters’ employer declined to comment for this story.

Corrina’s first concern was for Cheryl, who started showing symptoms of the virus around the same time that she did. Cheryl’s job as a utilization review technician required face-to-face interaction with patients to verify their insurance and discuss workers’ compensation. She had underlying health conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis.

“Corrina worked with people with RA when she was on Pima reservation, so she knows the effects of having it,” Mary, her mother, said. “I think that’s what worried her the most, because she thought it might make [Cheryl’s] immune system weaker.”

As a utilization review technician at Tuba City Regional Health Care in Arizona, Cheryl Thinn had face-to-face contact with patients to verify their insurance and discuss workers’ compensation. She had underlying health conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis. (Chris Thinn)

Chris remembers calling Cheryl on her 40th birthday, March 19. Cheryl joked about how, as the baby of the four siblings, she was “still young and pretty.” But she also complained that it was difficult for her to breathe. She was admitted to the Tuba City hospital the next day.

Corrina’s condition worsened as well, and she checked herself into the emergency room at Tuba City on March 21. Hospital staff tried assisted-breathing treatments on her, to no avail.

Cheryl was airlifted to Flagstaff Medical Center on March 24. She never knew that Corrina was briefly in the hospital with her.

Corrina was airlifted to Banner Thunderbird Medical Center in Glendale later that night.

Chris said that the last time she spoke with Corrina, she was still in the ER. “She just messaged us saying she was going to get flown out, that she loves us and that she was going to be back,” Chris said. “That was the last time we heard from her.”

Because of shortages, the sisters weren’t tested for COVID-19 until they were transferred out of Tuba City. They both tested positive and were then intubated at their respective hospitals. Cheryl died on April 11, and no family members were allowed to be with her.

“I couldn’t even hold my baby,” her mother said. “I couldn’t even hold her hand when she passed.”

The family had a small service before burying Cheryl next to their father, Navajo Police Sgt. Jimmie Thinn Sr., and Cheryl’s ex-husband, who died in January. Even after their marriage ended, the two remained close and co-parented Cheryl’s son, Kyle.

Chris said the whole experience felt “very lonely.”

Numbed by the pain of Cheryl’s death, the family shifted their focus to Corrina.

“You tell yourself that we just need to get her healthy enough to come home,” Chris said. “And then all of the sudden, she’s gone.”

Corrina died on April 29 — 18 days after her sister’s death and two weeks after her birthday, which she spent on a ventilator. Although she was unconscious, her nurse sang “Happy Birthday.”

Corrina’s oldest son, Gary Werito Jr., had tried for weeks to take leave from his Fort Bliss Army post in El Paso, Texas. His superiors declined his requests out of concerns he might contract the virus while on leave.

Corrina Thinn with her sons, Michael (center) and Gary Werito Jr. (Chris Thinn)

Separated from his mother by hundreds of miles, Werito tried to reach her through prayer.

“I would burn cedar,” he said. “I was trying to talk to my mom. I was telling her, ‘Mom, you’re going to get through this. You’re going to come home. You’re going to meet your granddaughter.'”

Werito and his wife were expecting their second child. The baby would have been Corrina’s first granddaughter.

Werito remembers his mother as a “model Navajo.”

“She left the reservation to get an education, and then she came home,” he said. “She could have worked anywhere else as a social worker, but she chose to help her own people.”

Before becoming a social worker, Corrina worked for the Tuba City Police District for more than 10 years. She ended her law enforcement career as a senior police officer.

Goldtooth, the sisters’ friend and colleague, said Corrina was particularly effective at the hospital because she spoke English and Navajo fluently. The Native language helped the U.S. win World War II as a secret code for communications because it remained mostly unwritten at the time.

“A lot of people aren’t fluent in Navajo anymore,” she said. “When elderly people would come [to the hospital], they don’t speak a lot of English. She was there to talk with them. It would really surprise people.”

Cheryl was more soft-spoken than her sister. Mary remembers her as empathetic and insightful. Her siblings often sought her advice.

“That’s what we miss about her,” Mary said. “She might be the quiet one, but she always has important things to say to us.”

Cheryl Thinn and her son, Kyle (Chris Thinn)

Both sisters left behind young sons. Corrina’s son Michael is 14, and Cheryl’s son just turned 12. The cousins are keeping each other company, reminding Mary of the way her daughters behaved.

Honoring her former service with the Tuba City Police District, law enforcement escorted Corrina’s body from Flagstaff to Tuba City. Her family was humbled by the outpouring.

“We had people lined up honoring her return,” Mary said. “They paid their respects, flying their flags. Some officers were standing along the road saluting her.”

Since June, the Navajo Department of Health has enforced strict curfews during the week and lockdowns over the weekend. Those measures have been effective, as they’ve seen cases decline over the past two months. The Navajo Nation began its first reopening phase in mid-August, allowing most businesses to operate at 25% capacity.

In late July, Werito left the Army for good and came home to Tuba City. His daughter was born on Aug. 5 in the same hospital where his mother and aunt worked. Her middle name is Lois, the same as Corrina’s.

Werito said he sometimes forgets his mother is gone and expects her to come home from work.

“My grandmother told me it’s a little peace of mind that I’m home now,” he said. “It kind of fills that void that my mom and my aunt left.”

This story is part of “Lost on the Frontline,” an ongoing project from The Guardian and Kaiser Health News that aims to document the lives of health care workers in the U.S. who die from COVID-19, and to investigate why so many are victims of the disease. If you have a colleague or loved one we should include, please share their story.

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.