[UPDATED Sept. 10]

Theresa Andrews’ 21-year-old daughter, Olivia, is hooked on heroin — and struggling to get medication to help kick her addiction has only added to the “hell,” Andrews said.

A few years ago, the San Diego mother called dozens of doctors before finding one who would prescribe her daughter buprenorphine, a widely used medication that quells heroin cravings.

Then, Andrews faced another hurdle at the pharmacy: She discovered that her top-notch health coverage, which she gets through her job, requires pre-authorization each month before she can take the medication home to Olivia.

The pre-authorization process creates a three-day delay that Andrews fears could push Olivia into a relapse. So she skips insurance and pays $250 for the medication out of her own pocket, she said.

“It’s really, really frustrating,” said Andrews, 47, a vice president for a local association of Realtors. “I’m fortunate enough that I can afford it.”

Last week, California lawmakers sent a bill to Gov. Jerry Brown that could make it easier for people like Olivia Andrews to get treatment. Under the measure, private insurers must cover medications for opioid addiction without requiring preapproval.

The bill also would require insurers to cover naloxone, an overdose reversal drug, without pre-authorization.

“This bill would normalize and standardize [opioid treatment] and make it treatable like diabetes,” said Dr. Chwen-Yuen “Angie” Chen, an assistant clinical professor at Stanford University who specializes in addiction.

That proposal is among 14 approved by the California legislature before it adjourned last week that would help opioid users break their addictions — or prevent people from using in the first place. One measure would improve treatment programs for kids. Another would allow San Francisco to establish “safe injection” sites, where people could inject illegal drugs under medical supervision. Two other bills would provide for the education and certification of more doctors to treat addiction.

Gov. Jerry Brown has until Sept. 30 to sign or veto the proposals. He has already signed three of the bills.

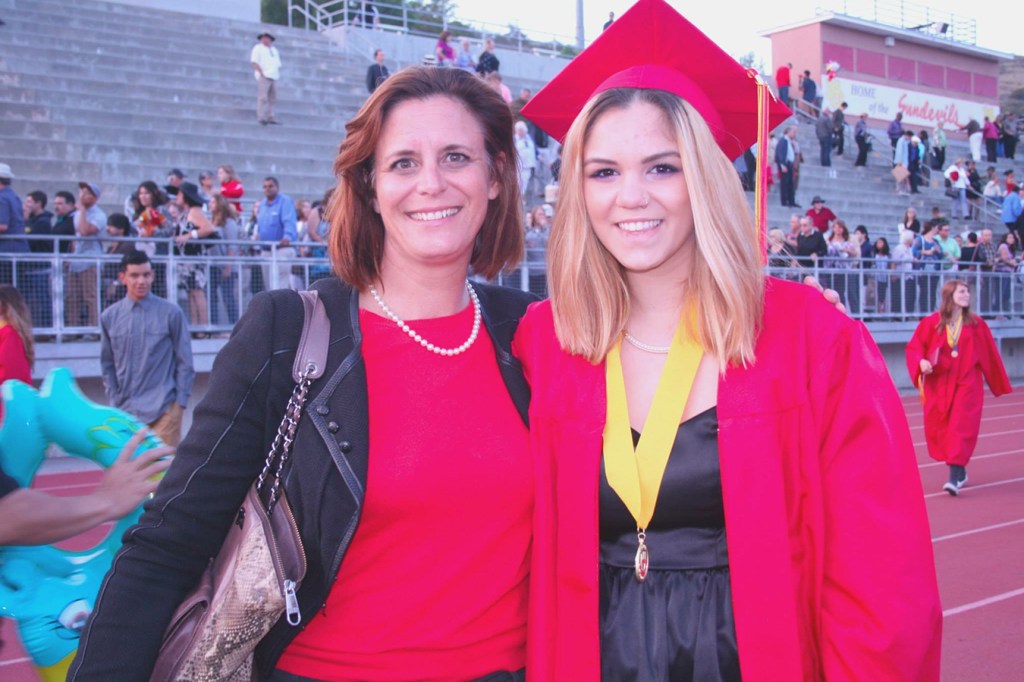

Because she wants to avoid her insurance plan’s preapproval process, Theresa Andrews pays out-of-pocket for medication to treat daughter Olivia’s opioid addiction. A bill approved by the state legislature would require private insurance plans to cover standard opioid addiction medications with no pre-authorization.(Courtesy of Theresa Andrews)

The measure that would expand coverage of medications for people with private insurance, like Andrews and her daughter, specifies certain drugs, such as buprenorphine, methadone and naltrexone, that addiction specialists use to wean patients off of illicit and prescription opioids.

The proposal, by state Assemblyman Joaquin Arambula (D-Fresno), would require insurers to cover at least one form of each of the medications. For instance, buprenorphine comes in tablet, injection and other forms, and under the bill, an insurer would have to cover only one of those.

Insurers oppose the measure, arguing that it would drive up the cost of care by forcing health plans to cover expensive treatments. An analysis by University of California researchers projects the bill would cost employers, individuals and Medicaid insurers about $25 million a year in additional costs related to higher premiums and out-of-pocket expenses.

Mary Ellen Grant, spokeswoman for the California Association of Health Plans, said insurers should be allowed to steer patients toward lower-cost therapies that are equally effective.

The California Society of Addiction Medicine supports the coverage requirement, but said almost all insurance plans already cover some sort of addiction treatment — many without preapproval requirements.

Dr. David Kan, president of the association’s board and a Walnut Creek-based addiction medicine specialist, said he would like the legislature to consider broader measures that guarantee patients coverage for any medication their doctors prescribe.

Other opioid-related proposals that lawmakers sent to Brown include:

- A measure to allow drug counselors to be paid for providing therapy via telemedicine to people enrolled in Medi-Cal, the state’s public insurance program that covers more than one-third of Californians.

- A proposal that would require doctors and dentists to offer patients a prescription for naloxone whenever they prescribe opioid painkillers.

- A bill that would allow California to link its opioid prescription database to those of other states so providers can track patients and prevent them from seeking opioid prescriptions at doctors’ offices across state lines.

- A measure that would direct state health care officials to create guidelines for substance abuse treatment programs for children and adults up to age 26 by July 2021.

- A proposal to require doctors to learn about the risks of opioid addiction as part of pain management education training. A separate initiative would allow doctors to become certified to treat addiction as part of their continuing medical education requirements.

Assemblywoman Susan Talamantes Eggman (D-Stockton) introduced the bill that would allow the city of San Francisco to establish “safe injection sites.” One such venue already exists in Vancouver, British Columbia, and others are being considered in New York City, Philadelphia and Seattle.

Laura Thomas, California director of the Drug Policy Alliance, an organization that advocates for science-based drug policies and is a primary sponsor of the legislation, said safe injection sites could prevent drug deaths because staff would be on hand to reverse overdoses, and drug users who use the sites would be more likely to seek treatment.

“The evidence and common sense say it will work,” Thomas said, “but the laws stand in the way.”