During Anne Soloviev’s semiannual visit to Braun Dermatology & Skin Cancer Center in Washington, D.C., in January, the physician assistant diagnosed fungus in two of her toenails. Soloviev is vigilant about getting skin checks, since she is at heightened risk for skin cancer, but she hadn’t complained about her toenails or even noticed a problem.

The assistant noted some unusual discoloration where the nail meets the skin. “They took a toenail clipping and said, yeah, you have a fungus,” Soloviev recalled.

So the PA called a prescription into a specialty pharmacy with mail-order services, which would send medication to Soloviev’s Capitol Hill home.

It seemed like an easy fix to an inconsequential health issue. “I did not ask how much it cost — it never crossed my mind, ever,” said Soloviev, a former French teacher, who still works part time.

Then the bill came.

Patient: Anne Soloviev, 77 on March 18, of Washington, D.C.

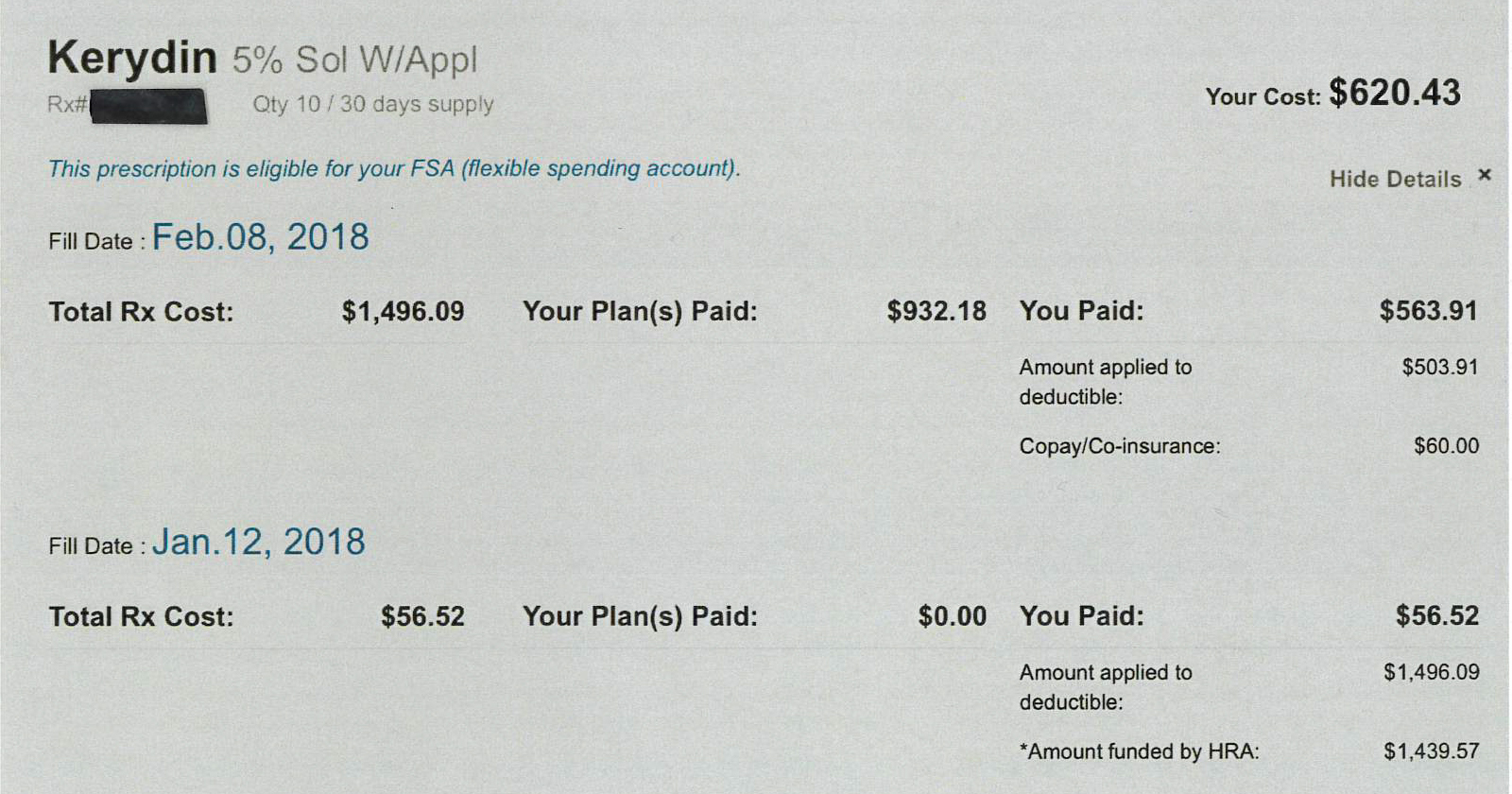

The Bill: $1,496.09 for Kerydin, a topical medication that treats toenail fungus. Originally produced by Anacor Pharmaceuticals Inc., it is now a product of Sandoz, a Novartis division.

Service Provider: My Express Care Pharmacy, plus Braun Dermatology & Skin Cancer Center

The Medical Treatment: Shortly after the physician assistant phoned in the prescription to My Express Care Pharmacy, in Maryland, the pharmacy contacted Soloviev for her health insurance information.

Soloviev is covered by Medicare, Parts A and B, and has supplemental insurance through her late husband’s government health benefits that covers prescription drugs. She also has a health reimbursement account (HRA), which contains almost $1,500 pretax dollars each year to pay for uncovered medical expenses. She typically uses that pot of money to cover copays for the other medicines she takes regularly.

Kerydin, the toenail medication, arrived by overnight mail, and an automatic refill came a few weeks later. She began swabbing it on the two toenails, as directed, having been told it would take about 11 months to treat the fungus.

She thought little of it.

Anne Soloviev’s prescription for Kerydin, at $1,496.09 per monthly refill, wiped out her entire health reimbursement account for the year. (Courtesy of Anne Soloviev)

But when Soloviev went to her local CVS to pick up another medication — a statin that is usually paid for by her HRA — she discovered her reserve was empty.

Unbeknownst to her, Kerydin, which it turned out costs nearly $1,500 per monthly refill, had wiped out her entire reimbursement account.

What Gives: We’re talking about mild toenail fungus. The price tag is difficult to rationalize, experts said.

“Reality check — this is $1,500 for a medicine to treat [it],” said Wendy Epstein, an associate law professor at DePaul University, who researches health care law. “That’s quite a chunk of change.”

Leslie Pott, Sandoz’s vice president of communications, explained that Kerydin is patent-protected and priced “at parity” with its one market competitor, Jublia. She also pointed out that to secure a place on an insurer’s list of approved drugs — its formulary — the drugmaker often had to offer substantial discounts to insurers and various middlemen. “We have no visibility into the extent to which these discounts are passed onto patients or payers,” she wrote in an email.

When Anne Soloviev visited the dermatologist in January, the physician assistant diagnosed fungus in two of her toenails and gave her a prescription for a topical medication. “I did not ask how much it cost — it never crossed my mind, ever,” Soloviev said. (Cheryl Diaz Meyer for KHN)

There are many prescription treatment options for toenail fungus — both older medicines in pill form and newer topical treatments such as Kerydin, said Dr. Shari Lipner, an assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medicine and director of its nail unit. The patient in this case would have been a candidate for “quite a few” of them.

Patients are likely to pay less for the pills, for which a course of treatment lasts three months, compared with the newer topical treatments, she said, adding that the pills also seem to have greater efficacy.

In its application for Food and Drug Administration approval granted in 2014, Anacor Pharmaceuticals highlighted that a yearlong treatment of Kerydin completely cured toe fungus in 6.5 percent of patients for one trial, and 9.1 percent of patients in another.

Over-the-counter treatments are also available, but there’s not much data on them, Lipner said.

Xavier Davis, Braun Dermatology & Skin Cancer Center’s practice manager, said a drug’s price tag simply isn’t a factor when prescribers recommend a course of treatment.

“When our providers are treating patients, we’re not treating them based on what the cost’s going to be. We look for what’s the best care for the patient,” Davis said. “If the patient calls and says that’s too expensive, then we’ll look for alternatives.”

Kavita Patel, a nonresident fellow at the Brookings Institution and a practicing physician, said this process contributes to the problem. “My sister’s a dermatologist, and she’ll do the same thing — she’ll prescribe and she doesn’t know. You’re getting at many layers of how [messed] up the system is, starting with the doctor doesn’t know.”

And patients often don’t see the actual price. Or they see it too late, when they’re at the pharmacy counter picking up medicines they have been told they need or in a roundabout way discover unexpected payouts.

In January, Soloviev’s insurance plan was billed the full price of Kerydin. Of that, $1,439.57 came from her HRA. The difference, $56.52, was covered by a patient-assistance program from the drug manufacturer, explained Jonathan Lee, a pharmacist for My Express Care.

In February, when Soloviev’s prescription was refilled, her plan was again billed the full drug price. But she didn’t know about that either. A manufacturer coupon was applied to cover what remained of her insurer’s $2,000 annual deductible and the $60 copay. Her insurance then kicked in to pay the difference.

Such patient-assistance programs and coupons are meant to insulate patients from cost sharing, so that they don’t feel a pinch from a drug’s price. But in this case, the drugmaker’s patient-assistance program apparently took effect only once Soloviev’s HRA has been wiped out, allowing the manufacturer to maximize revenue from both patient and insurer.

DePaul University’s Epstein said it took her “15 minutes to figure out what was going on” here. And, unlike the average patient, she studies this issue for a living.

Lee, the pharmacist, said even he didn’t realize that money could be withdrawn directly from a patient’s HRA without her knowledge, and he’s been in the business for the better part of a decade.

None of that is consolation for Soloviev, who said: “I just find it is outrageous for a fungal medicine to cost $1,400, to be prescribed for 11 months, and for neither the PA nor the pharmacy to warn you,” Soloviev said.

Resolution: Though she has told My Express Care not to renew the prescription, Soloviev’s HRA is depleted. For the rest of the year, she’ll have to pay out-of-pocket costs for any other medications, an expense she hadn’t planned on.

The Takeaway: For even the most informed of patients, getting a new prescription can mean walking through a financial minefield. And Soloviev hit a number of booby traps.

Bottom line, experts say, medical professionals should make the patient aware if they prescribe a high-priced medicine and explain why it’s beneficial.

Patients should play defense and ask their physicians about the cost of every new prescription. They should ask again at the pharmacy — even if that means calling a mail-order pharmacy. Because costs can vary depending on each patient’s coverage, they may need to contact their insurance carrier or the PBM that handles their medicine claims.

And if the cost is extremely high, they should ask their doctor about generic or over-the-counter alternatives.

“This is an important component of the decision a patient’s going to make,” Epstein said. “If it’s toenail fungus and not life-or-death, it strikes me … an individual might want to have relevant data.”

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.