ALHAMBRA, Calif. — It’s Tuesday morning, and teacher Tamya Daly has her online class playing an alphabet game. The students are writing quickly and intently, with occasional whoops of excitement, on the little whiteboards she dropped off at their homes the day before along with coloring books, markers, Silly Putty and other learning props — all of which she created or paid for with her own money.

Two of the seven children in her combined third and fifth grade class weren’t home when Daly came by with the gift bags. One of the two managed to find her own writing tablet, thanks to an older brother, but the other can’t find a piece of paper in her dad’s house. She sits quietly watching her classmates on Zoom for half an hour while Daly tries futilely to get the father’s attention. Maybe the student is wearing earphones; maybe the father is out of the room.

As children head back to school online across California and much of the nation, some of the disparities that plague education are growing wider. Instead of attending the same school with similar access to supplies and teacher time, children are directly dependent on their home resources, from Wi-Fi and computers to study space and parental guidance. Parents who work, are poor or have less education are at a disadvantage, as are their kids.

Daly teaches elementary students with special needs. The children in her class, who have a variety of diagnoses and intellectual disabilities, are at even higher risk — they can’t work independently and need more hands-on instruction. “The more they’re not getting those kinds of accommodations, the further they’re going to fall behind,” said Allison Gandhi, a managing director in special education at the nonprofit American Institutes for Research.

Educators and families fear devastating long-term consequences from COVID-19 for the nearly 800,000 California children who received special education services. So, in early August, the state announced it was developing a waiver application process for schools, even in COVID-plagued counties, that want to bring small groups of these students back for in-person education.

“There are simply kids that will never, ever have that quality learning that we all desire to advance online, no matter what kind of support we provide, even if we individualize it,” Gov. Gavin Newsom said at an Aug. 14 news conference.

Online learning is interfering with the students’ individualized education programs, or IEPs — legal agreements among families, school districts and specialists that set academic and behavioral goals for students and the services they’re entitled to.

The gap in online learning experience is sharply visible in Daly’s class, and the parents’ role is crucial. For parents who don’t have to work, distance learning may be tense and time-consuming, but it becomes part of a daily routine to be endured until the pandemic ebbs. For others, schooling is an unworkable nightmare burdening parents already stretched to their limits.

School started Aug. 12. By day five, Daly knew which children had the luxury of a stay-at-home parent and which were being supervised by older siblings. She knew which students struggled to get online on time every day — a new state requirement for all virtual learners — and which ones needed reminding to eat breakfast before class started.

She also knew, from last spring, that most of the parents couldn’t print the worksheets she had uploaded to Google Classroom. Their printers were broken, or printer ink cost too much, or they didn’t have printers. For this semester, she set up a time every Thursday for parents to drive by the school and pick up packets for the following week.

Daly works at Emery Park Elementary School in Alhambra, east of downtown Los Angeles, where two-thirds of the students qualified last year for free or reduced-price school meals. The school has loaned about 80% of the 434 students Chromebooks because they didn’t have computers at home, said principal Jeremy Infranca.

Like most schools in California, Emery Park started the school year in virtual classrooms — the safest option for a state with a stubbornly persistent infection rate. The Alhambra school district has yet to decide whether to apply for a waiver to bring students with special needs back on campus. Infranca and Daly would like to — if they can secure COVID-19 protective gear for themselves and their students, and if families feel comfortable with it.

In the meantime, Daly is doing her best to accommodate her families, which isn’t easy. Parents have told her to limit live group instruction to an hour a day, so as not to interfere with child care schedules or the laptop needs of other children in the household. To make up for the reduced time, Daly records several 15- to 30-minute videos explaining the work to be done and plans to schedule an individual session with each child once a week.

“I choose to be positive about this experience, and I choose to communicate and do my best to reach out to the students and connect with parents and family members,” said Daly. “We just need to be proactive, and also a little patient.”

Tamya Daly teaches elementary students with special needs — those who can’t work independently and need more hands-on instruction. When she takes attendance every morning, she greets each student personally, hoping the “circle time” will help the kids stay connected. (Anna Almendrala)

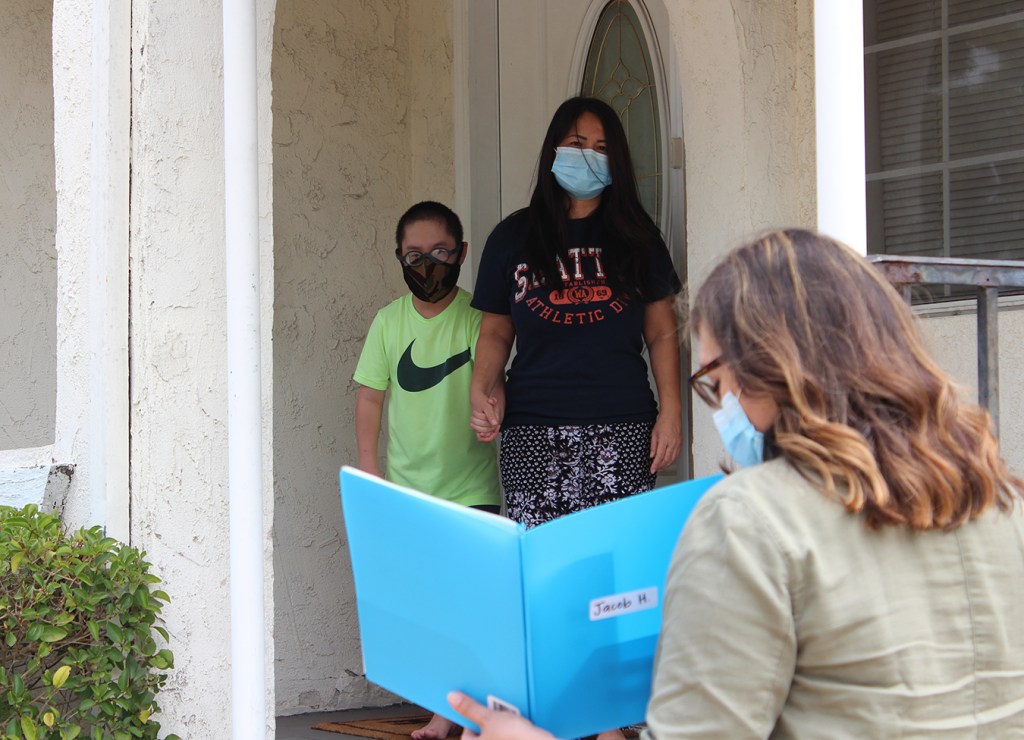

Tamya Daly delivers school supplies to Jasmine and her mother, Ivy, a stay-at-home parent. Ivy supervises Jasmine’s classwork and behavioral therapy online, and also helps Jasmine’s younger sister with her online classes. (Anna Almendrala)

Families have different opinions about whether to return their kids to the schoolhouse. It often depends more on a family’s desperation over child care than consideration of COVID-19 risks.

Cat Lee, 44, was nervous at first when she realized she had to take on the bulk of hands-on teaching for her son, Jacob, a fifth grader in Daly’s class.

“I wondered, would I be able to teach him as well, and would he be able to learn it?” she said.

Lee is a stay-at-home mom, and so far she has been able to stick to the schedule Daly lays out. She’s there with Jacob at every Zoom session and logs onto the Seesaw app to go through all the assignments. She praised Daly for her curriculum, which she felt was better and easier to teach than what the family received back in March. But she had reservations about her son’s new normal.

“It’s really slowing down his learning; plus, he doesn’t interact with kids anymore,” said Lee.

Still, if she had the chance to send Jacob for in-person learning now, Lee wouldn’t take it. She has concerns about their immune systems — Lee had a kidney transplant five years ago, and Jacob was born at just 27 weeks’ gestation — and is holding out for a COVID vaccine before allowing Jacob to resume his normal activities.

Not that she doesn’t have doubts.

“My fear is that he’s going to be home for so long, he’ll be so used to it and he won’t want to go back to school,” she said.

Danielle Musquiz, a 32-year-old mother with five elementary school-aged boys — four adopted from a relative — would favor a return to school. She gets three or four hours of sleep each night because of her 90-hour workweek with two jobs, as a home aide and a cashier at a regional park.

Four of her sons receive special education services, including an adopted middle child who is in Daly’s class and has cognitive delays linked to fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. The children, crowded together at the dining room table or in the living room, listen to their classes with earphones to keep from disturbing one another, which means she can’t hear a teacher calling out to her from the screen.

The four kids have individual education programs, but it’s hard for Musquiz to oversee them “with the minimal amount of time I have at home,” she said. She’s feeling overwhelmed by having to coordinate, supervise and respond to teachers, counselors and therapists for each child.

Musquiz is working longer hours than before the pandemic, and she picks up shifts at the park when the boys’ former stepfather takes them for the weekend.

“I’m slowly starting to say — and I know that this sounds bad — I don’t care anymore about the kids’ schooling,” Musquiz laughed nervously. “I feel like it’s chaos, and I’m drowning.”

To help with child care, her mother lives with the family Monday through Thursday, and her sons spend Thursday nights at her sister’s house. On Fridays, nine kids are all streaming their classes online from that house. On a recent Friday, the Wi-Fi broke, prompting a call from the school of one of her sons asking why he had left class early.

If she had the opportunity, Musquiz would send her children back to in-person learning in a heartbeat.

“None of my kids are really going to learn what they need to,” said Musquiz. “They need hands-on, they need interaction, they need motivation, and these classes are not doing that for them.”

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.