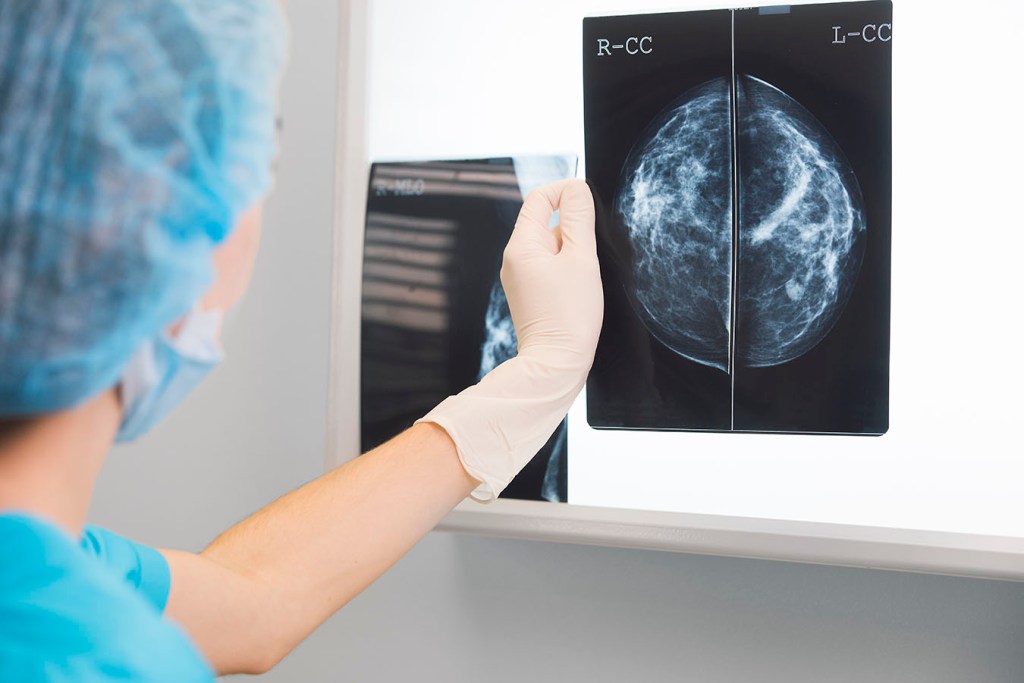

Surgery is a mainstay of breast cancer treatment, offering most women a good chance of cure.

For frail nursing home residents, however, breast cancer surgery can harm their health and even hasten death, according to a study published Wednesday in JAMA Surgery.

The results have led some experts to question why patients who are fragile and advanced in years are screened for breast cancer, let alone given aggressive treatment.

The study examined the records of nearly 6,000 nursing home residents who had inpatient breast cancer surgery the past decade. It found that 31 to 42 percent died within a year of the procedure. That’s significantly higher than the 25 percent of nursing home residents who die in a typical year, said Dr. Victoria Tang, lead author and an assistant professor of geriatrics and hospital medicine at the University of California-San Francisco.

Although her study doesn’t include information about the cause of death, Tang said she suspects that many of the women died of underlying health problems or complications related to surgery, which can further weaken older patients. Patients who were the least able to take care of themselves before surgery, for example, were the most likely to die within the following year. Dementia also increased the risk of death.

It’s unlikely that many of the deaths were due to breast cancer, which often grows slowly in the elderly, Tang said. Breast cancers often take a decade to turn fatal.

“When someone gets breast cancer in a nursing home, it’s very unlikely to kill them,” said study co-author Dr. Laura Esserman, director of the UCSF breast cancer center. “They are more likely to die from their underlying condition.”

Yet most patients in the study got sicker and less independent in the year following breast surgery.

Among patients who survived at least one year, 58 percent suffered a serious downturn in their ability to perform “activities of daily living,” such as dressing, bathing, eating, using the bathroom or walking across the room.

Women in the study, who were on average 82 years old, suffered from a variety of life-threatening health problems even before being diagnosed with breast cancer. About 57 percent suffered from cognitive decline, 36 percent had diabetes, 22 percent had heart failure, 17 percent had chronic lung disease, and 12 percent had survived a heart attack.

The high mortality rate in the study is striking because breast surgery is typically considered a low-risk procedure, said Dr. Deborah Korenstein, chief of general internal medicine at New York’s Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

The paper provided an example of how sick, elderly people can suffer from surgery. An 89-year-old woman with dementia who underwent a mastectomy became confused after surgery and pulled off all her bandages. Health care workers had to restrain her in bed to prevent her from pulling off the bandages again. The woman died 15 months later of a heart attack.

Surgery late in life is more common than many realize. One-third of Medicare patients undergo surgery in the year before they die, according to a 2011 study in The Lancet. Eighteen percent of Medicare patients have surgery in their final month of life and 8 percent in their final week.

Nearly 1 in 5 women with severe cognitive impairment, such as Alzheimer’s disease, get regular mammograms, according to a study in the American Journal of Public Health.

The new study leaves some important questions unanswered.

The paper didn’t include healthier nursing home residents who are strong enough to undergo outpatient surgery, said Dr. Heather Neuman, a surgeon and associate professor at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health. These women may fare better than those who are very ill.

Esserman and Tang said their findings suggest doctors need to treat breast cancer differently in very frail patients.

“People think, ‘Oh, a lumpectomy is nothing,’” Esserman said. “But it’s not nothing in someone who is old and frail.”

In recent years, doctors have tried to scale back breast cancer therapy to help women avoid serious side effects. In June, for example, researchers announced that sophisticated genetic tests can help predict which breast cancers are less aggressive, a finding that could allow 70 percent of patients to avoid chemotherapy.

The Medicare database used in this study didn’t mention whether any of the patients had chemotherapy, radiation or other outpatient care. So the UCSF researchers acknowledged that they can’t rule out the possibility that some of the women suffered complications due to these other therapies. In general, however, authors noted that only 6 percent of nursing home residents with cancer are treated with chemotherapy or radiation.

The authors said doctors should give very frail patients the option of undergoing less aggressive therapy, such as hormonal treatments. In other cases, doctors could offer to simply treat symptoms as they appear.

The new study raises questions about the value of screening nursing home residents for breast cancer, Korenstein said. Although the American Cancer Society hasn’t set an upper age limit for breast cancer screening, it advises women to be screened as long as they’re in good health and expected to live at least another decade.

Residents of nursing homes generally can’t expect to live long enough to benefit from breast screening, Korenstein said.

“It makes no sense to screen people in nursing homes,” Korenstein said. “The harms of doing anything about what you find are far going to outweigh the benefits.”

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.