As Americans prepare to cook and consume nearly 50 million turkeys on Thanksgiving Day, an ongoing outbreak of salmonella poisoning linked to the poultry means food safety at home is more critical than ever.

Federal health officials have identified no single source of the outbreak of Salmonella Reading, which has sickened at least 164 people in 35 states during the past year.

As of Nov. 5, the bacterial strain has led to 63 hospitalizations and, in California, one death.

Many who fell ill reported preparing or eating such products as ground turkey, turkey parts and whole birds. Some had pets who ate raw turkey pet food; others worked at turkey processing plants or lived with someone who did.

Late Thursday, Jennie-O Turkey Store Sales LLC of Barron, Wis., recalled more than 91,000 pounds of raw ground turkey products that may be connected to the illnesses.

There is no U.S. requirement that turkeys or other poultry be free of salmonella — including antibiotic-resistant strains like the one tied to the outbreak — so prevention falls largely to consumers.

That means acknowledging that the Thanksgiving turkey you lug home from the grocery store is likely contaminated, said Jennifer Quinlan, an associate professor in the Nutrition Sciences Department at Drexel University.

“They absolutely should assume there’s a pathogen,” she said.

Last year, right after the holiday season, Quinlan and her colleagues surveyed more than 1,300 U.S. consumers about their turkey-handling habits. Most, they found, fail to follow safe practices, despite decades of public health warnings.

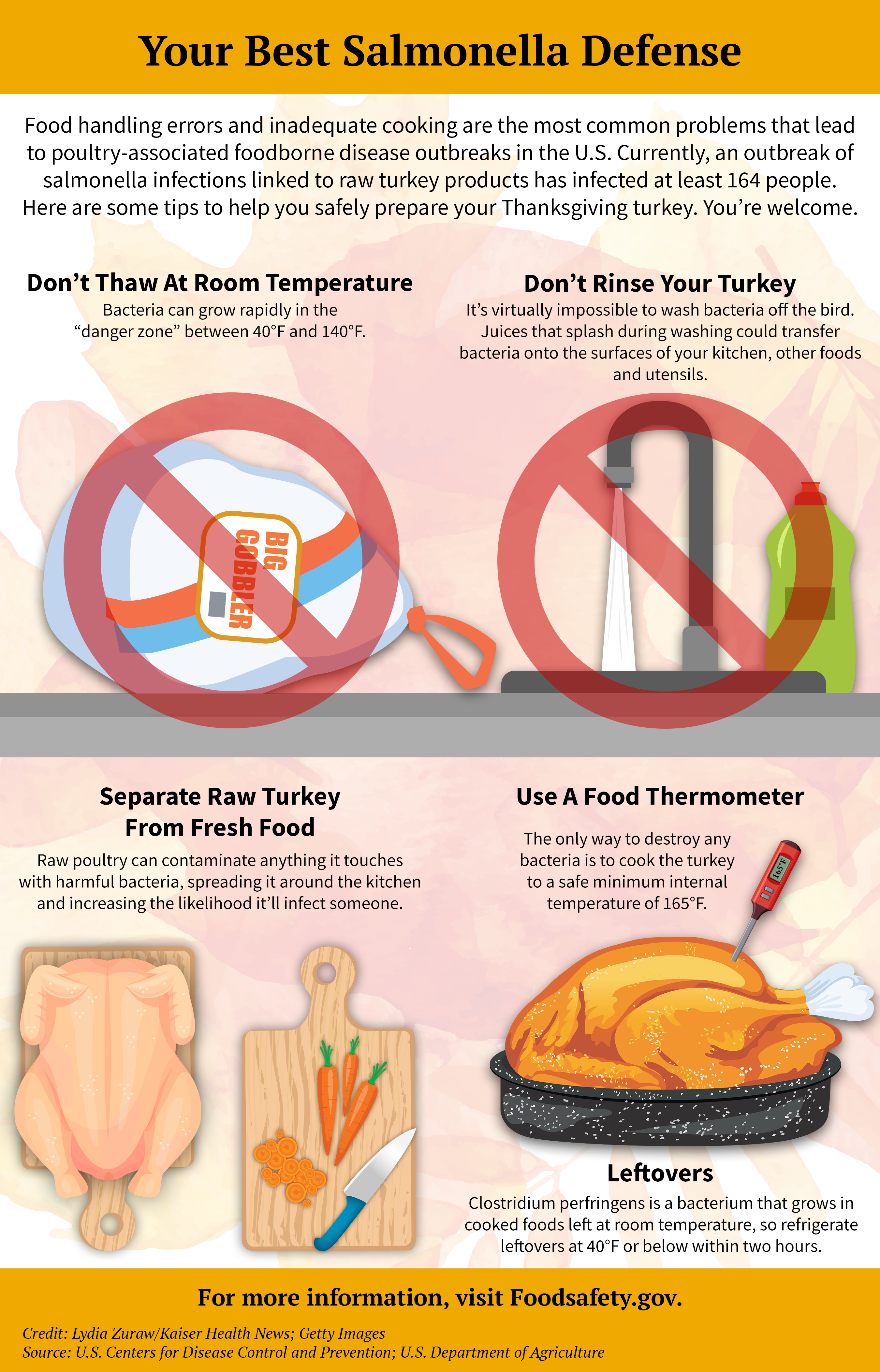

Ninety percent of those surveyed washed raw birds in the sink, even though that can spread dangerous bacteria. Fifty-seven percent reported always or sometimes stuffing a turkey before cooking instead of baking dressing separately, and 77 percent said they left a cooked bird in a warm oven or at room temperature.

Such practices can allow the growth not only of salmonella but other bad bugs, such as campylobacter and Clostridium perfringens, she said.

“All of these illnesses could have been prevented. There’s either cross-contamination going on in the home, or there’s not thorough cooking.”

Other experts contend that simply telling consumers to handle food properly is unfair and ineffective. Regulators and industry should be responsible for preventing contamination in the first place.

“They ought to be going after these guys like gangbusters,” said Carl Custer, a food safety microbiology consultant who spent decades at the U.S. Department of Agriculture. “This is a seriously virulent strain.”

This month, Custer renewed calls for pathogenic strains of salmonella to be declared “adulterants” in poultry, which would require the USDA to test products and recall those contaminated with the bacteria.

The USDA classified E. coli O157:H7 as an adulterant in ground beef after the deadly 1993 Jack in the Box hamburger outbreak. After that, the rate of those E. coli infections plummeted. Since then, the agency has named six additional strains as adulterants in certain beef products.

Efforts to ban drug-resistant salmonella from meat and poultry have stalled, however, despite years of demands from consumer advocacy groups and lawmakers.

In February, USDA officials rejected a 2014 petition from the group Center for Science in the Public Interest to declare certain strains of drug-resistant salmonella to be adulterants, saying the group failed to distinguish strongly enough between resistant and non-resistant salmonella.

In 2015, Democratic congresswomen Rosa DeLauro of Connecticut and New York’s Louise Slaughter introduced a bill that would have defined resistant and dangerous salmonella as adulterants and given USDA new power to test and recall tainted meat, poultry and eggs. It was not enacted.

“It’s very hard to get attention to food safety issues in this current political climate,” said Sarah Sorscher, CSPI’s deputy director of regulatory affairs.

Outside observers said there’s little political will for taking on the nearly $5 billion-a-year U.S. turkey industry, as well as regulators.

“I don’t see a lot of traction for making it an adulterant right now,” said Kirk Smith, director of the Minnesota Integrated Food Safety Center of Excellence.

“Salmonella is still common enough that it would be hugely impractical and costly to make it an adulterant,” he added. “It would double the cost of poultry.”

In a sharply worded statement, USDA officials refused to publicly name the producers, suppliers and brands linked to the turkey outbreak because of potential impact on the industry.

Because the outbreak strain of salmonella has been found at turkey-processing plants, in workers and in a wide range of food products, it will take a broad effort to detect and eradicate the source, said Smith, the Minnesota food safety expert.

“It should be a whole-system approach, starting with controls on the farm, all the way through to educating consumers as best we can,” he said.

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.