A few months ago, Kourtnaye Sturgeon helped save someone’s life. She was driving in downtown Indianapolis when she saw people gathered around a car on the side of the road. Sturgeon pulled over, and a man told her there was nothing she could do: Two men had overdosed on opioids and appeared to be dead.

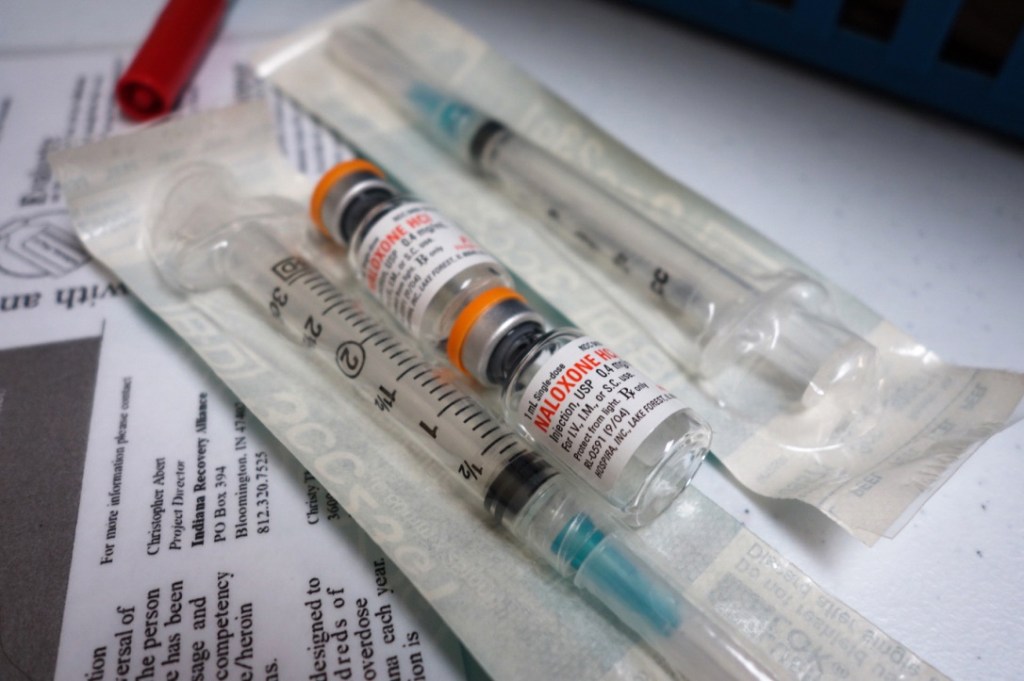

“I kind of recall saying, ‘No man, I’ve got Narcan,'” she said, referring to a brand-name version of the opioid overdose antidote, naloxone. “Which sounds so silly, but I’m pretty sure that’s what came out.”

Sturgeon sprayed a dose of the drug up the driver’s nose and waited for it to take effect. About a minute later, she said, the paramedics showed up.

“As they were walking towards us, the driver started slowly moving,” she said. Both people survived.

Sturgeon had the drug with her because she works for Overdose Lifeline, a nonprofit devoted to distributing naloxone. But many bystanders in that situation would be unprepared to help.

Last month, U.S. Surgeon General Jerome Adams issued an advisory urging more Americans to learn to use naloxone and to carry it with them in case they encounter someone who has overdosed.

With the increase in overdoses nationwide, the advisory suggests that lay responders — people who may witness an overdose before police or emergency medical services arrive — can play a critical role in saving lives.

But if you’re not a medical professional, getting a dose of naloxone can be difficult. It is a prescription drug and normally a doctor or nurse would have to directly prescribe it for the person at risk of overdosing. Corey Davis, an attorney for the National Health Law Program, said that creates a barrier for people with addiction.

“A lot of people at risk of an overdose don’t have contact with a medical provider or they’re afraid because of stigma,” he said.

To broaden access, every state and Washington, D.C., have passed laws making it easier for friends, family members or bystanders to get and use naloxone. Just how easy it is depends on your state, or even the pharmacy you use.

Davis said most states allow something called third-party prescribing, which lets doctors prescribe naloxone to someone who knows the person at risk of an overdose. And most states have passed some kind of Good Samaritan law providing legal immunity for people who administer the drug or call 911.

Davis said another type of law allows a kind of prescription called a standing order.

“But instead of having a person’s name on it, it has a group of people,” said Davis.

A standing order could apply, for example, to anyone who takes opioid painkillers or suffers from addiction. Or, Davis said, “anybody who might be in a position to assist someone, which, unfortunately, today means essentially everybody.”

In his home state of Indiana, Surgeon General Adams signed a statewide standing order in 2016, while serving as the state’s health commissioner. It allows pharmacies, local health departments or nonprofits that register with the state and follow certain requirements to dispense the drug to anyone who requests it.

But two years later, only about half of Indiana pharmacies are registered, and local advocates say many people, even some pharmacists, are still unaware of the law.

Even if you understand the laws regulating naloxone in your state — and you feel comfortable asking for it at the pharmacy counter — there’s still the cost, which has gone up in recent years. Two pharmacies near WFYI in Indianapolis stock naloxone. One charged $80 for two doses of the generic form of the drug. The other charged $95 for two doses of Narcan, a brand-name version.

“It’s expensive,” says Brad Ray, a researcher at Indiana University’s School of Public and Environmental Affairs. “People who are users are scraping money together to buy drugs. They’re not prepared to buy naloxone with that money.”

More than a dozen U.S. senators have signed a letter urging Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar to negotiate with drug companies to lower the price of naloxone.

For people who can’t afford the drug, Ray said, health departments and nonprofits can help. Laws in many states allow these organizations to dispense naloxone to lay responders.

Indiana’s health department used federal and state funds to purchase nearly 14,000 naloxone kits since 2016, the state reported. The state distributes those free doses through county health departments. But nearly half of Indiana counties didn’t request kits. And the majority of the kits went to first responders.

Local health departments, Ray said, need to work harder to get naloxone to people who might use it. People who use drugs, after all, may not feel comfortable going to the government for naloxone.

“Getting it in the hands of users — that’s the trick we need to figure out,” Ray said.

Davis said there is one change that could really help. The Food and Drug Administration or Congress could make naloxone an over-the-counter medication to make it easier to access, and maybe cheaper. FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb has the authority to do so, Davis said, but so far he has not.

This story is part of a partnership that includes WFYI, Side Effects Public Media, NPR and Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.