McALLEN, Texas — Edgar carries a red folder bulging with paperwork, bills and medical records. Before his lung cancer diagnosis in September, he had about $11,000, he said, money he was saving to purchase a used truck and to pay an immigration attorney to pursue legal residency.

By February, it was gone, and Edgar was relying on friends and family to cover doctor appointments, food and other basics. His treatment had been complicated by a collapsed lung.

“I’m not able to work — I’m breathing with just one lung,” said the 50-year-old painter, who asked to be identified by only his first name because he’s an undocumented immigrant from Mexico.

Edgar had fallen into a black hole for treatment that extends across two South Texas border counties, a stretch with more than 1.2 million residents that’s roughly half the size of Connecticut.

There are no public hospitals in the Rio Grande Valley counties of Cameron and Hidalgo, which includes the city of McAllen. In Texas, public hospitals are typically funded by a separate tax on property and provide care to indigent residents in the county where they’re located. Hidalgo County residents have recently voted against such a new property tax.

Most hospitals in the region are for-profit facilities. Although a network of nonprofit clinics has developed over the years, their focus is typically primary care and not surgery, imaging or other specialized treatment.

Nearly 30% of residents are uninsured, three times the national average of 8.8%, and their median household income is less than $38,000 a year, while the national average is $56,500.

Texas has not expanded Medicaid access, and it is difficult for adults to qualify for Medicaid. With few exceptions, an adult is eligible only if he or she is a parent, and then the income cutoff is quite low, no more than $3,827 annually for a parent with two children, according to Anne Dunkelberg, who oversees health policy at the Austin-based Center for Public Policy Priorities.

Uninsured adults who develop cancer — or might have cancer, but need further testing to be sure — have nearly no access to affordable medical care, according to local clinicians and directors of safety-net clinics. The options are even more constrained for adults, who are either undocumented or live in families with mixed legal status.

To reach public hospitals roughly 250 miles north in San Antonio or 350 miles away in Houston, a cancer patient will likely cross at least one of the border checkpoints — where agents can stop drivers and ask about citizenship and travel plans — that dot Texas roads and lead out of the Rio Grande Valley. That’s an increasingly risky proposition in recent years, said Rebecca Stocker, executive director at Hope Family Health Center, a nonprofit clinic in McAllen. Another option, traveling south to Mexico for what’s often more affordable care, forces undocumented patients to choose between treating their cancer and leaving family members behind, perhaps permanently.

“So then you’re stuck in Mexico,” Stocker said. “You may have a husband here, you may have a wife here, you may have your kids here, and you have no way of getting back to them.”

Sitting at El Milagro Clinic, another primary care clinic in McAllen, Edgar recounted how he first developed a nagging cough and, nearly two years later, shortness of breath and worsening exhaustion that forced him to seek medical help.

He has undergone numerous tests, as well as radiation and chemotherapy, at a for-profit hospital with some discounts and financial help along the way, but he didn’t know how long he could rely on friends and family to pay for further medical care. His chemotherapy was free through a pharmaceutical company’s assistance program, he said, although he paid for related hospital and physician fees.

Edgar said he was able a number of years ago to navigate the checkpoints, in part because of his pale skin and reddish hair. But these days, amid heightened immigration scrutiny, he wouldn’t attempt to pass through them to reach more affordable care elsewhere in the state.

“If I do that, and they catch me, it’s the end,” he said. “I’ve been living here almost 16 years trying to do everything right, and I don’t want to mess up with that.”

Carlos Rivera had been losing weight and living with fierce abdominal pain before being diagnosed with colon cancer. He initially faced problems getting treatment until getting insurance under the guidance of Ziomara Tirado, a care coordinator at the Hope Family Health Center, a nonprofit clinic in McAllen, Texas.

Life-Threatening Delays

For uninsured patients in the Rio Grande Valley, and particularly those who aren’t U.S. citizens, a cancer diagnosis presents a “devastating” situation, said Dr. Elena Marin, chief executive officer of Su Clinica, a large federally qualified health center with multiple primary care locations.

“It’s either a death sentence,” Marin said, “or it’s a prolonged time before you can raise the money in order to get in for some of the treatment that you need.”

Visiting with clinicians and clinic directors along the 60-mile stretch from McAllen to Brownsville, it seems as if everyone has a story about life-threatening delays for uninsured adults with cancer. (A nonprofit Rio Grande Valley clinic affiliated with Texas Children’s Hospital and Baylor College of Medicine treats children regardless of insurance or legal status.)

They talk about patients holding barbecues and other fundraising efforts to try to cobble together money from family and friends to afford surgery, chemotherapy or the biopsy to figure out if they have cancer. A needle biopsy can cost between $1,500 and $2,000, according to a white paper published by a local coalition last fall highlighting lack of access to specialty care.

“How many barbecue plates will it take?” asked Ann Williams Cass, executive director of Proyecto Azteca, which works with low-income communities, including areas called colonias that may have limited access to electricity, utilities and other basic services. “Most of them, of course, succumb to metastatic disease before they’re able to get help.”

A spokesman for Texas Oncology, one of the largest cancer practices in the valley, declined to discuss how physicians there provide treatment to uninsured patients. In a brief statement, the practice said it seeks to help patients, “including working with foundations and other organizations that support patients in need.”

Dr. Todd Shenkenberg, a Harlingen oncologist who describes himself as one of the few who routinely treat uninsured patients, said he has developed referral arrangements with local surgeons and specialists. He also relies on pharmaceutical assistance programs to help patients cover costly medications.

He told of patients who had ended up at his office because they couldn’t get into an oncologist elsewhere. “To me, it just shouldn’t be,” he said.

‘The Fear Overwhelms’

The cost to see a specialist, whether for cancer or other treatment, can be insurmountable, said Sister Phylis Peters, who leads Proyecto Juan Diego, a nonprofit organization based in Cameron Park, a large colonia north of Brownsville. “They won’t tell you they don’t go, but they just don’t go,” Peters said.

Sister Phylis Peters, who leads Proyecto Juan Diego, a nonprofit organization based in Cameron Park, a large colonia north of Brownsville, Texas, says the cost to get into a specialty physician’s office, whether for cancer or another medical issue, can be insurmountable for poor people living in the Rio Grande Valley.

The Catholic nun is credited with helping to transform Cameron Park into a community with paved roads, taquerias and other small businesses attached to mobile homes, and a community center is in the works. But Peters no longer allows colorectal- and other cancer-screening initiatives to come into the community.

“I don’t believe in screening if we can’t help the patient,” she said, “because I think the psychological trauma and the fear overwhelms.”

A patient at the Hope clinic, Carlos Rivera, had been losing weight and living with fierce abdominal pain. But he continued working, installing office furniture in Texas, until he was visiting his wife in Mexico shortly after last Christmas and couldn’t get out of bed.

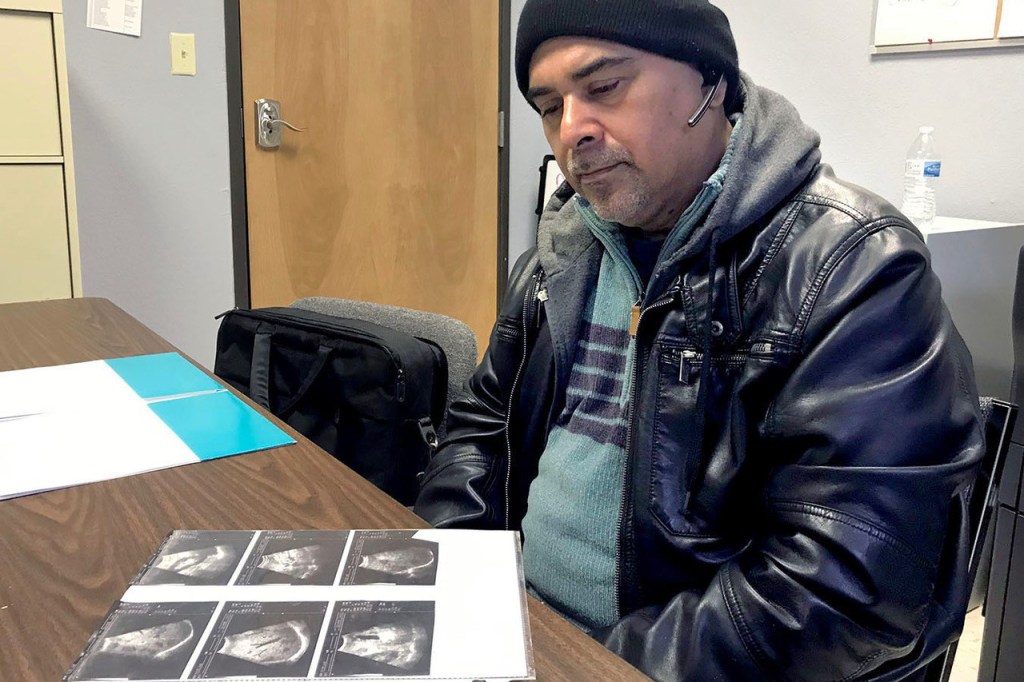

Rivera pulled out the imaging scans that were taken that day at the Mexican clinic, pointing to the black marks on his liver. In early January, a physician in McAllen informed Rivera he had colon cancer that had spread to his liver, and there was no cure. Clinicians and outreach workers began advocating on his behalf, and Rivera got insurance coverage so he could start chemotherapy.

Ziomara Tirado, a care coordinator at Hope, recalled when Rivera first approached her in frustration, saying he wanted to fight the cancer but couldn’t qualify for Medicaid and couldn’t afford treatment himself. “In Spanish, he just said to me, `So what does this mean? Someone who doesn’t have insurance doesn’t get saved?’”

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.