Last year, nearly 60 percent of Maine residents voted to expand the state’s Medicaid program — an option provided by the Affordable Care Act that would extend health insurance to tens of thousands of the state’s low-income people.

But the state’s Republican governor, Paul LePage, a longtime opponent of Medicaid expansion, has refused to implement the policy because he doesn’t want to raise taxes to pay the state’s share of the cost.

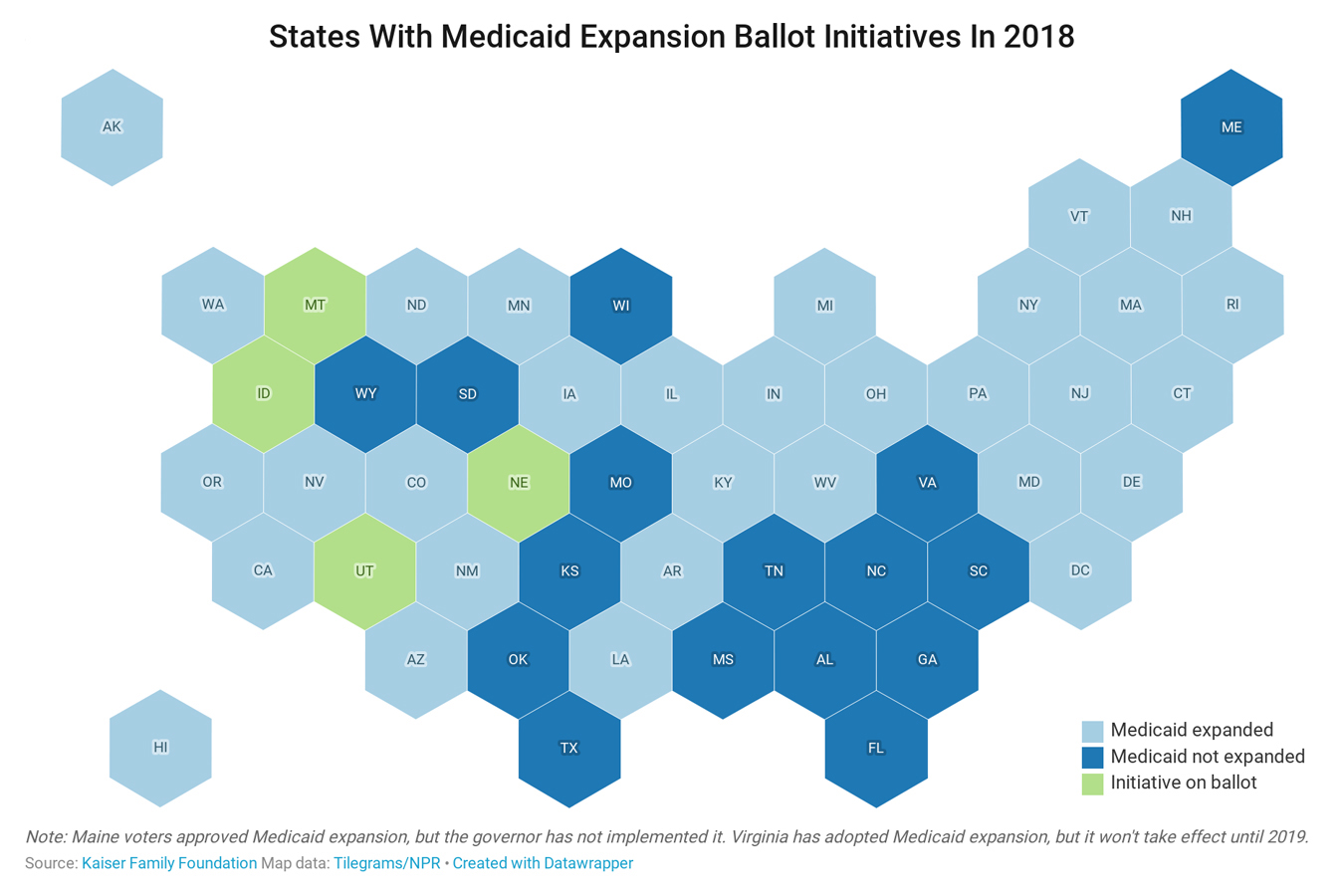

The impasse highlights how the intense political push and pull over Medicaid expansion persists even when voters bypass legislators and decide the issue directly at the ballot box. Nevertheless, four more states — Idaho, Montana, Nebraska and Utah — will give voters in November’s elections the opportunity to resolve the dispute.

“It’s always treacherous” for politicians to raise taxes, said Matt Salo, who heads the National Association of Medicaid Directors. “But there are ways around it. You can figure out ways that are politically palatable.”

When the ACA’s Medicaid expansion took effect in 2014, proponents say, it set up an enticing deal. It allowed states to cover people with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level, including childless single adults.

The federal government paid the entire cost of the new enrollees. In 2017, states were to take on 5 percent of those costs. By 2020, that amount will increase to 10 percent.

States that didn’t pursue the expansion pay as much as half the cost of coverage. And, in 2018, median eligibility for a family of four was 43 percent of the poverty level, or about $10,800. No childless adults were eligible.

So far, 33 states plus the District of Columbia have opted to expand, extending coverage to almost 12 million Americans, according to federal estimates last year. In those states, the expense ranges from tens of millions of dollars to hundreds of millions.

Rather than being a cash drain, many health policy researchers and economists note, expansion has generally boosted state economies, with higher employment, reduced state spending on health care services for the uninsured and consumer spending elsewhere that would have gone to health care.

“The state savings are so significant, they make it much more manageable,” said Adam Searing, an associate professor of practice at Georgetown University’s Center for Children and Families. “The issue of how it gets paid for — it’s still an important issue, but it’s not as front and center.”

Different approaches work for different states, Salo said, and all invite political complications.

In Montana, voters are considering Initiative 185, a ballot question that would continue the state’s Medicaid expansion and fund it by increasing what is known as a “sin tax” on tobacco products, including electronic cigarettes.

It’s a counterintuitive double whammy in such a conservative state: persuading voters first to favor an Obamacare policy, and second to finance it with a tax hike.

By taking on cigarettes, the campaign has incurred the wrath of Big Tobacco, which has put forth more than $12 million in contributions and expenditures to fight the measure.

“Anytime you go up against the tobacco industry, you are mainly going to have them as your opponent,” said Amanda Cahill, who directs government relations for Montana’s American Heart Association chapter and is part of the “Yes on I-185” campaign.

Voters can be skittish about a tax increase, she said, but many are receptive to the campaign’s argument that it pays off in the long term.

New Hampshire took a parallel “sin tax”-type approach. It uses money from an alcohol tax to help fund expansion, a deal negotiated this year.

In Utah, voters will consider newly expanding Medicaid and funding it with a 0.15 percent increase to the state’s sales tax, though the hike would exempt groceries. Current polling suggests strong voter support. Nebraska and Idaho also have Medicaid expansion on the ballot, though they would punt the funding question to state legislatures.

Other states have tried a different strategy: shielding consumers from direct taxes and instead financing expansion through taxes on industry players that benefit from Medicaid expansion. The most notable example: hospitals. For these facilities, reducing the number of uninsured, low-income people reduces the burden of uncompensated care and improves their bottom line. Research from states that have already expanded Medicaid supports this idea.

Virginia, Oregon and Colorado already have such taxes or fees in place. (Oregon voters in January approved a tax on both health insurance and hospitals to fund expansion.)

But it hasn’t been easy. Virginia’s legislature voted this summer to expand Medicaid eligibility after failing five times. During Statehouse debates, funding was a “very significant concern,” said Michael Cassidy, president of the Commonwealth Institute for Fiscal Analysis, a Richmond-based think tank that has long supported the policy.

Proponents of expansion showed economic projections that Virginia would benefit financially, since fewer uninsured people would need state-funded health services, and the injection of federal cash would boost the state economy.

The legislature eventually approved a tax on hospitals, by garnering support from their trade group, the Virginia Hospital and Healthcare Association. But the path to approval was “quite contentious,” Cassidy said. Critics argued the cost was too great and could drive up health care expenses.

Medicaid advocates haven’t begun planning ballot initiatives for 2020 yet, but there are six states that haven’t expanded eligibility where voters could take on the question directly: Florida, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, South Dakota and Wyoming.

As political analysts have long argued, the issue isn’t entirely about funding. States can surmount that obstacle if there is political will.

“If you’re talking about why did certain states not do the expansion, the fear of the cost — while a real issue — has never been within the top three of the actual reasons why they actually didn’t do it,” Salo said. “It all has been political and ideological.”