On Tuesday, the Trump administration announced $100 million in supplemental funding for community health centers to support the response to the coronavirus pandemic.

“Health centers are playing a critical role,” said James Macrae, associate administrator at the federal Bureau of Primary Health Care.

About 29 million people in the U.S. rely on community health centers, which provide care to low-income and uninsured patients. As hospitals take on more COVID-19 patients, community health centers are reworking how they care for patients. Some safety-net clinics have instituted new infectious disease protocols and temporarily shifted resources away from routine primary care.

The new funding goes to 1,381 community health centers (many of which operate multiple clinics), primarily to support more COVID-19 testing, telehealth and the acquisition of personal protective equipment.

“It’s nowhere near what is needed, but we are thankful,” said Bob Marsalli, CEO of the Washington Association for Community Health, a group representing community health clinics in Washington state.

Marsalli said community health centers in the state are under increasing financial strain as they ramp up for the coronavirus battle, while also losing some key sources of funding.

“[Our clinics] are reallocating their workforce intelligently, but frantically, to keep up with the demand,” said Marsalli.

Rapidly Redesigning Systems

Under normal circumstances, HealthPoint, a community health center in Auburn, Washington, would encourage patients to walk into the clinic for all their medical needs, whether refilling a prescription or learning about nutrition.

“Usually our lobby is slammed,” said Dr. Esther Johnston. “It’s open space and everyone is together.”

But recently only a few patients in surgical masks were waiting for appointments. And Johnston is telling patients to stay away unless they absolutely need care.

“It is a bit frustrating and demoralizing, but it’s the reality of the situation,” she said.

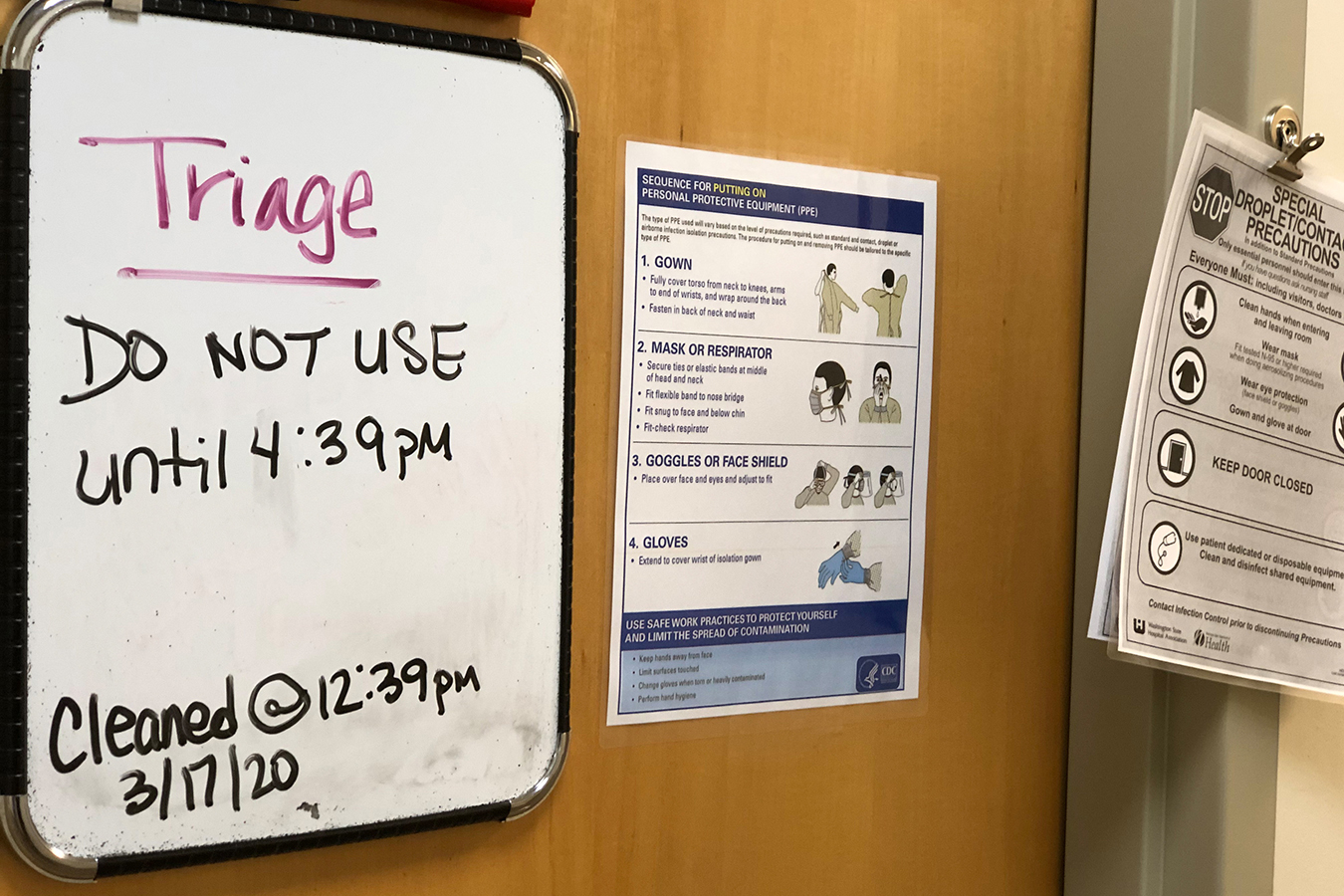

HealthPoint runs more than a dozen clinics throughout western Washington. Now, at the entryway of its clinics, staff query everyone to identify COVID-19 symptoms and monitor patients to make sure they remain at a distance from one another once inside.

Johnston said the clinic was not set up to house an influx of patients with infectious diseases. There are limited exam rooms and each one needs to be shut down and cleaned after a patient suspected of having COVID-19 comes in.

“We just don’t have enough space to be able to do that on a routine basis,” she said.

Like many community health centers, HealthPoint’s model is built around bringing people into clinics for primary care. Now the organization is taking new precautions to prevent the spread of coronavirus and keep staff safe. (Will Stone for KHN)

Johnston worries about what’s coming as COVID-19 cases rise in her area.

“We pride ourselves on being a primary care home,” Johnston said. “We don’t have enough N95 masks, nor, to be honest, were we prepared for a situation where everyone had to be properly fitted.”

HealthPoint’s chief medical officer, Dr. Judy Featherstone, said most appointments are now done over the phone. Her staff is fielding calls from people concerned about symptoms, as well as new patients who want to have a doctor in case they contract the COVID-19 virus.

“It is a bit like taking 20 years of work and redesigning it in a week,” said Featherstone. “I think we are anticipating potential workforce problems.”

Like many clinics in Washington, HealthPoint has set up outdoor testing sites, but the supply of kits and personal protective gear, or PPE, limits the number of patients who can be tested for COVID-19.

New Financial Strain On Clinics

As fewer patients come in for care, the leadership worries about the center’s financial future. Clinics have switched to telephone-based appointments, but it took several weeks for Washington’s Medicaid program to adjust how it pays for those visits. Meanwhile, community health centers are eliminating routine dental visits, a key funding stream.

“You take those three factors … and you have already started to lose revenue before you’re gearing up for new ways of providing care,” said Michael Erikson, CEO of Neighborcare Health, which serves more than 70,000 Washington residents, over half of them on Medicaid. “We are on a pathway to losing $3 million a month.”

The Washington Association for Community Health projects that the cutback in dental care could lead to a $250 million shortfall for the state’s community health center system over the next nine months.

Vital Role In The Health System

Community clinics play an important role in serving patients who otherwise might have no place to go besides the ER. Erikson said his organization is trying to relieve some pressure on the hospital system by seeing patients with urgent health care issues not related to COVID-19.

“For instance, a wound care patient who has underlying diabetes, you do not want to expose that patient to a potential COVID environment,” said Erikson.

Some community clinic leaders now worry about losing staff to suspected or actual coronavirus infection.

“It is very critical that the clinics stay at full staff so only those who are critically sick are cared for at the hospital,” said Sheila Berschauer, CEO of Moses Lake Community Health Center, a rural health care provider in Washington that serves about a third of its county’s population of about 100,000.

If even five to 10 health care workers fall ill, Berschauer said, that could strain her organization and, as a result, possibly overwhelm the local hospital.

She said some patients still don’t appreciate the severity of the pandemic and become upset when they are sent to the outdoor testing site rather than into the clinic.

A health care worker at a health center outside Seattle said several patients have misrepresented their COVID-19 risks in order to get past screening.

“We had a patient make it all the way into the exam room before she revealed that her partner is COVID exposed, and she is feeling ill,” the employee said. The worker is worried about losing their job for speaking out, so NPR and KHN are not using the person’s name.

Health care workers who saw the patient were not wearing PPE because those limited supplies are reserved for patients known to be at risk of COVID-19.

“Now all of the providers and staff in that facility need to start self-monitoring for signs of infection,” the employee said. “If they get infected, then the entire clinic closes. It’s a big deal.”

This story is part of a partnership between NPR and Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.