Mary Epp awoke from a deep sleep to the “high, shrill” sound of her dialysis machine’s alarm. Something was wrong.

It was 1 a.m. and Epp, 89, was alone at home in Marion Junction, Ala. No matter. Epp has been on home dialysis since 2012, and she knew what to do: Check the machine, then call the 24/7 help line at her dialysis provider in Birmingham, Ala. to talk to a nurse.

The issue Epp identified: Hours before, a woman she hired to help her out had put up two small bags of dialysis solution instead of the large ones, and the solution had run out.

The nurse reassured Epp that she’d had enough dialysis. Epp tried to detach herself from the machine, but she couldn’t remove a cassette, a key part. A man on another 24/7 help line run by the machine’s manufacturer helped with that problem.

Was it difficult troubleshooting these issues? “Not really: I’m used to it,” Epp said, although she didn’t sleep soundly again that night.

If policymakers have their way, older adults with serious, irreversible kidney disease will increasingly turn to home dialysis. In July, the Trump administration made that clear in an executive order meant to fundamentally alter how patients with kidney disease are managed in the U.S.

Changing care for the sickest patients — about 726,000 people with end-stage kidney disease — is a top priority. Of these patients, 88% receive treatment in dialysis centers and 12% get home dialysis.

By 2025, administration officials say, 80% of patients newly diagnosed with end-stage kidney disease patients should receive home dialysis or kidney transplants. Older adults are sure to be affected: Half of the 125,000 people who learn they have kidney failure each year are 65 or older.

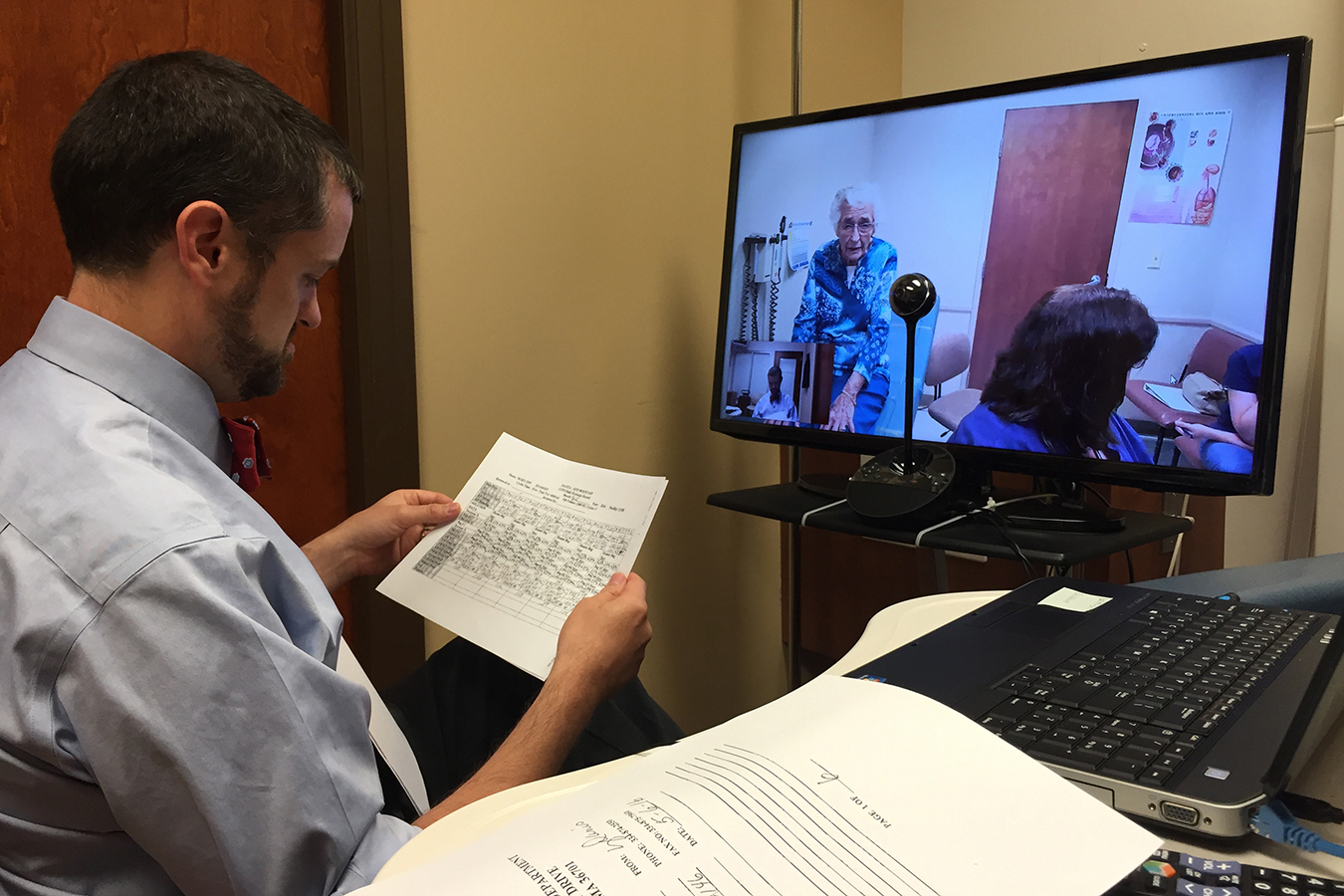

Mary Epp receives a telehealth consult from a team at a dialysis clinic in Birmingham, Ala., 90 miles away from her home in Marion Junction. Epp does peritoneal dialysis at home every night while she sleeps. (Courtesy of the University of Alabama at Birmingham)

Home dialysis has potential benefits: It’s more convenient than traveling to a dialysis center; recovery times after treatment are shorter; therapy can be delivered more often and more readily individualized, putting less strain on a person’s body; and “patients’ quality of life tends to be much better,” said Dr. Frank Liu, director of home hemodialysis at the Rogosin Institute in New York City.

But home dialysis isn’t right for everyone. Seniors with bad eyesight, poor fine-motor coordination, depression or cognitive impairment generally can’t undertake this therapy, specialists note. Similarly, frail older adults with multiple conditions such as diabetes, arthritis and cardiovascular disease may need significant assistance from family members or friends.

The burden of providing this care shouldn’t be underestimated. In a recent survey of caregivers providing complex care to family members, friends or neighbors, 64% identified operating home dialysis equipment as hard — putting this at the top of the list of difficult tasks.

What experiences do older adults have with home dialysis? Several seniors doing well on home-based therapies were willing to discuss this, but they’re a select group. Up to a third of patients who try home dialysis end up switching to dialysis centers because they suffer complications or lose motivation, among other reasons.

It takes determination. Jack Reynolds, 89, prides himself on being disciplined, which has helped him do peritoneal dialysis at home in Dublin, Ohio, seven days a week for 3½ years.

With peritoneal dialysis, the therapy that Epp also gets, a fluid called dialysate (a mix of water, electrolytes and salts) is flushed into a patient’s abdomen through a surgically implanted catheter. There, it absorbs waste products and excess fluids over several hours before being drained away. This type of dialysis can be done with or without a machine, several times a day or at night.

About 10% of patients on dialysis choose peritoneal therapy, including 18,500 older adults, according to federal data.

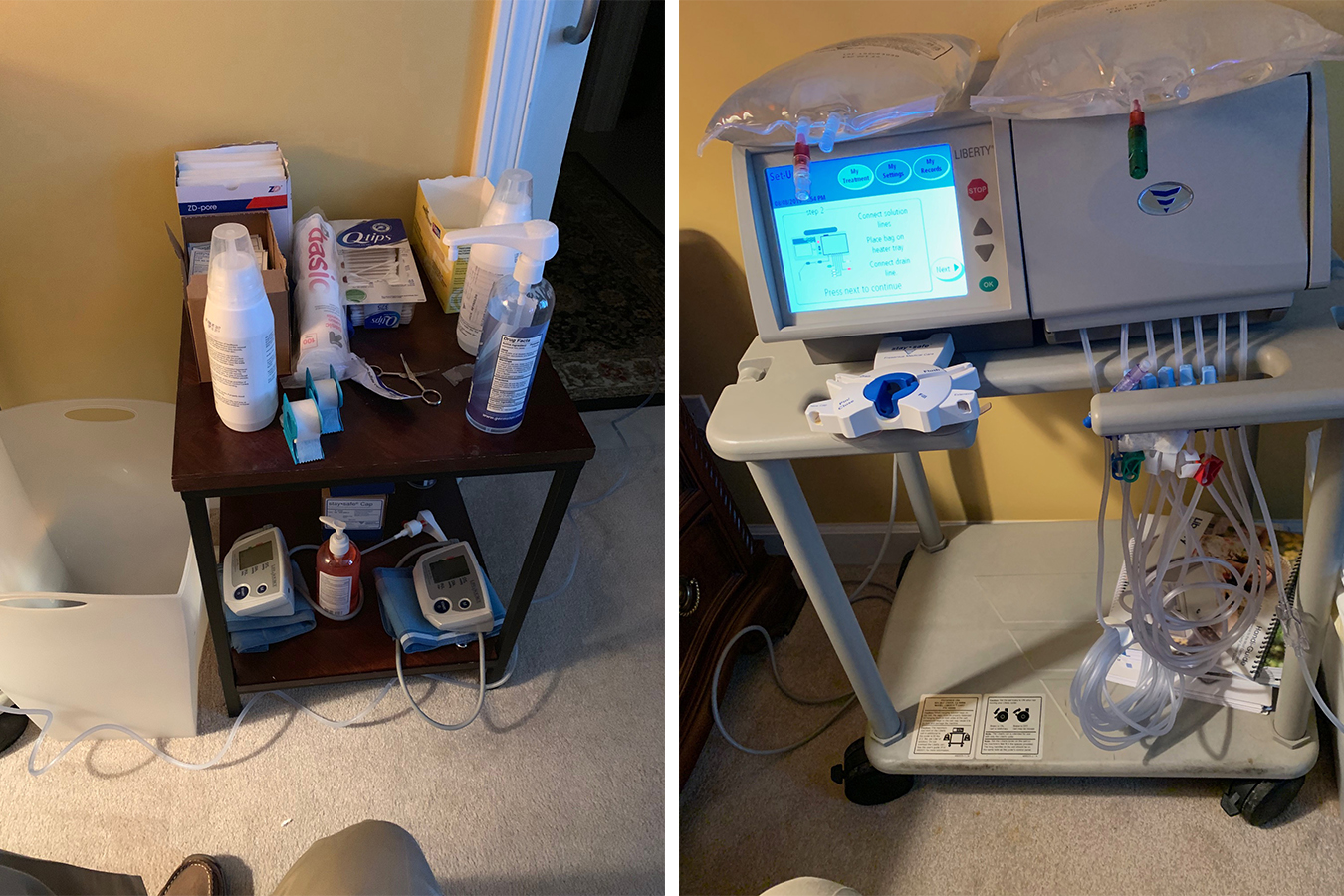

Reynolds prefers to administer peritoneal dialysis while he sleeps — a popular option. His routine: After dinner, Reynolds sets out two bags of dialysate, ointments, sterile solutions, gauze bandages and a fresh cassette for his dialysis machine with four tubes attached: two for the dialysate bags, one for his catheter and one to expel dialysate at the end.

Altogether, it takes him 23 minutes to gather everything, clean the area around his catheter and sterilize equipment; it takes about as much time to take things down in the morning. (Yes, he has timed it.) Just before going to sleep, Reynolds hooks up to his dialysis machine, which runs for 7.5 hours. (The amount and frequency of therapy varies according to an individual’s needs.)

“I live a normal, productive life, and I’m determined to make this work,” Reynolds said.

Jack Reynolds has been doing peritoneal dialysis at home in Dublin, Ohio, seven days a week for the past 3½ years. Each night he uses two bags of dialysate, ointments, sterile solutions, gauze bandages and a fresh cassette for his dialysis machine with four tubes attached: two for the dialysate bags, one for his catheter and one to expel dialysate ready to be discarded. (Courtesy of Jack Reynolds)

It took five surgeries to successfully implant a catheter on Reynolds’ left side because of scarring from previous abdominal surgeries. He has had to replace three malfunctioning dialysis machines and learn how to sleep on his right side, so the tube connected to his catheter isn’t compressed.

In the morning, his wife, Norma, cleans the area around his catheter, applies a gauze bandage and tapes an 18-inch extender attached to the catheter to his chest. He could do this himself, Reynolds said, but “I wanted her to have some part in all this.”

Training is demanding. In December 2003, when Letisha Wadsworth started home hemodialysis in Brooklyn, N.Y., she was working as an administrator at a social service agency and wanted to keep her job. Doing dialysis in the evening made that possible.

Home hemodialysis requires one to two months of education and training for both the patient and, usually, a care partner. With each treatment, two needles are stuck into an access point, usually in a vein in a patient’s arm. Through lines connected to the needles, blood is pumped out of the patient and through a machine, where it’s cleansed and waste products are removed, before being pumped back into the body.

Only 2% of dialysis patients chose this option in 2016, including 2,800 older adults.

Letisha Wadsworth began home hemodialysis 15 years ago in an effort to keep her job as a social service agency administrator. Doing dialysis at her Brooklyn, N.Y., home in the evenings made that possible. (Courtesy of Letisha Wadsworth)

The training was “rigorous” and “pretty scary for both of us,” said Wadsworth, now 70, whose husband, Damon, accompanied her. “We learned a lot about dialysis, but we still didn’t know about issues that could arise when we got home.”

Issues that Wadsworth has had to deal with: learning what to do if air got into one of the lines. Adjusting the rate at which her blood was pumped and flowed through the machine. And, recently, getting a medical procedure to fix the access site for her needles, which had clotted with blood.

Another issue: finding space for 30 large boxes of supplies (fluids, filters, needles, syringes and more) that Wadsworth orders each month. They’re stored in two rooms in her house.

Over the years, Wadsworth has talked a lot to family members and friends about kidney failure and dialysis. “I wish I’d known about the relationship between blood pressure and kidney failure a lot earlier,” she said. “I guess I thought all black people have high blood pressure: It just comes with the territory as opposed to what we can do to prevent it.” (High blood pressure puts people at risk of kidney failure.)

In 2013, Wadsworth had a stroke, which temporarily paralyzed her left side. “I used to set up the [dialysis] machine, but now I use a walker and I can’t really stand and set everything up the way I used to.” Damon, 73, does this for her.

Wadsworth’s current routine: Dialysis starts around 8 p.m. and goes for five hours, four days a week, in a dedicated room in her house. She passes the time eating dinner, watching TV, reading on her Kindle, talking on the phone, visiting with friends or playing Scrabble with Damon.

Like most patients on home dialysis, she gets blood tests once a month and visits her nephrologist two weeks later to review how she’s doing. A nurse, dietitian and social worker are also part of her team at the Rogosin Institute.

Damon, a psychotherapist, admits it isn’t easy to stick his wife with needles. “A lot of times, it hurts her, and it’s not fun for me to be the person doing that,” he said. “But it’s just part of my life now. We’re thankful that home dialysis exists and we’re lucky enough to be able to do it.”

It can be overwhelming. Sharon Sanders, 76, thought she had the flu last year when she had trouble breathing and keeping food down. But when she landed in the hospital, doctors told her that her kidneys were shutting down.

About half of the time, this is what happens to people who end up on dialysis: They learn suddenly that their kidneys aren’t working reliably anymore.

Like many people, Sanders was shocked. After going to classes and talking to a niece who’s a registered nurse, she decided on peritoneal dialysis. “I liked that I can do it at home, by myself, and I don’t have to stick myself with needles,” she said.

Training took about a week at a clinic in Mesa, Ariz. “It came very easy for me,” said Sanders, who lives in Gold Canyon, Ariz., and who began her nightly routine of six hours of peritoneal dialysis, five days a week, last August.

She doesn’t pay anything for the therapy, which is covered for her by Medicare and Tricare insurance, a benefit Sanders has because of her husband’s military service. (He died in 2017). Medicare Part B pays 80% of the cost of dialysis at home, and supplemental coverage (including, for instance, a Medigap policy, a retiree policy from an employer or Medicaid) generally picks up the remainder.

Sanders is a frequent visitor to Home Dialyzors United Facebook support group and another site, Home Dialysis Central. Another site, My Dialysis Choice, is a useful resource for people deciding whether home dialysis is right for them.

Even though Sanders, who has arthritis of the spine, doesn’t find her dialysis routine especially burdensome, she sometimes gets overwhelmed. “I don’t have any energy too much of the time,” she said. “I find myself thinking, What’s my purpose for doing this? Is it worth it if we’re all going to die anyway?’”

Finding needed help. Until last November, when her husband of 68 years died, Mary Epp relied on him to get her ready for peritoneal dialysis, which she receives every night while she sleeps for nine hours.

Now, an aide comes in a 7 p.m. to help Epp take a bath and set things up before dialysis begins an hour later. Another woman comes in at 5 a.m. to take her off dialysis, clean everything up and fix her breakfast.

“I’ve gotten a lot more feeble than I was” when home dialysis began in 2012, said Epp, who admitted she was “terrified” when a physician diagnosed her with kidney failure.

But the benefits of home therapy, which is overseen by a team at a dialysis clinic 90 miles away in Birmingham, remain worth it, she said. “You just go to bed and wake up the next morning and you’re ready to go and meet the day.”

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.