Erica Torres is one of the estimated 1.4 million Californians who live without health insurance largely because they are undocumented.

She was hopeful when President Barack Obama expanded deportation-relief programs for undocumented immigrants — a controversial move that would have put government-subsidized health care within her reach.

But last month’s Supreme Court decision suspending Obama’s order has derailed that aspiration, leaving Torres’ future — and her health insurance options — in limbo.

“I haven’t had insurance since my son [now 7] was born,” said the 44-year-old Torres, who lives in the Southern California suburb of Canoga Park. “I thought this was one possibility, that maybe I would qualify for Medi-Cal.”

For undocumented immigrants, finding affordable health care has been an ongoing battle. They’ve claimed some victories — undocumented children in California, for example, can now enroll in Medi-Cal, the state’s Medicaid program.

But there are few low-cost health care options for adults who are in the country illegally.

The U.S. Supreme Court’s split decision last month, which temporarily blocked Obama’s deportation-relief programs, leaves millions of undocumented immigrants in California and across the nation facing deep uncertainty.

Miranda Dietz, a researcher at the University of California, Berkeley Center for Labor Research and Education who has studied immigrants and health care, said the Supreme Court’s ruling means that fewer undocumented people in California will have access to health insurance, either from Medi-Cal, college enrollment or employer coverage.

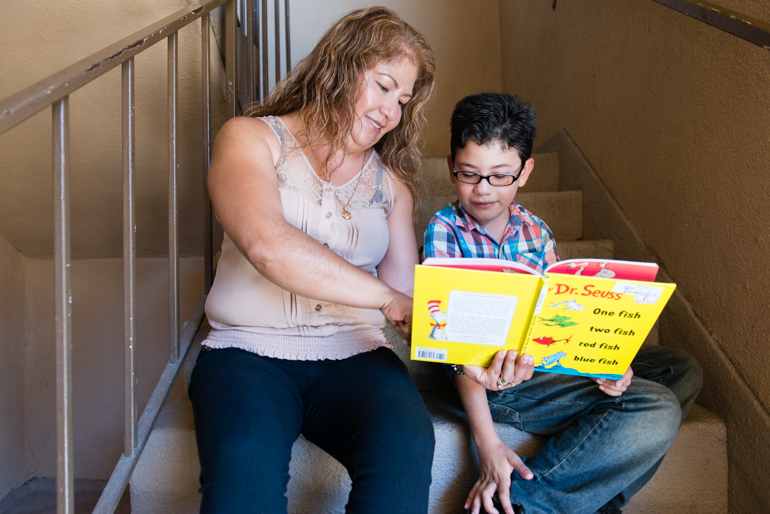

Torres immigrated to the United States from Mexico 17 years ago and hoped the Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents (DAPA) would allow her to apply for a work permit and Medi-Cal. (Heidi de Marco/California Healthline)

Torres, who came to the United States illegally 17 years ago, had set her hopes on one of the deportation-relief programs affected by the Supreme Court decision, known as Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents (DAPA). The program would grant adults who have lived in the country continuously since 2010 and have a U.S.-born child protection from deportation.

Eligibility for the program would allow this group of undocumented adults to apply for work permits. And in California, they also could apply for Medi-Cal, as long as they met the income criteria.

Because her son was born in the United States, Torres would be eligible to apply for DAPA. She already had gathered the paperwork she thought she’d need.

But last month’s Supreme Court decision let stand a lower court ruling that blocked the program, which had not yet taken effect because of the legal challenges. The ruling means that, at least for now, Torres still can’t apply for Medi-Cal.

“It was disappointing and frustrating,” Torres said. She had been feeling confident that she’d soon have a sense of security, and with it, access to basic preventive care.

The Supreme Court decision also blocked, at least temporarily, Obama’s planned expansion of another program, known as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), the controversial deportation-relief program for undocumented youth. The expansion would have raised the age limit for inclusion in the program, making it available to a larger group of people, who would have been eligible for Medicaid health coverage

California health advocates note that the Supreme Court’s ruling is temporary and will most likely be retried. Last week, the U.S. Department of Justice filed a petition with the Supreme Court, requesting a rehearing of the case. But if and when that rehearing will take place will likely depend on the result of presidential election.

The original DACA program, which has allowed 700,000 undocumented young people to stay in the U.S. since 2012, is not affected by the Supreme Court ruling. Current participants in that program retain their rights, including access to Medi-Cal for those living in California.

Researchers at UCLA’s Center for Health Policy Research and UC Berkeley’s Labor Center estimate that in California, between 310,000 and 440,000 undocumented adults could be eligible for Medi-Cal if the expansion of the two programs ultimately is allowed.

But how many immigrants actually would sign up is hard to determine, the researchers say. As of mid-2014, 154,000 people in California were granted protection under DACA, of which 125,000 were eligible for Medi-Cal. Yet fewer than 11,000 of them actually signed up for it, the UCLA and UC Berkeley research showed.

Torres reads to her U.S.-born son, Esau Rodriguez, 7, on the stairs of their apartment. DAPA, or Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents, would allow undocumented adults like Torres to seek protection from deportation if they lived in the country continuously since 2010 and had a U.S.-born child. (Heidi de Marco/California Healthline)

But those are just estimates, UC Berkeley’s Dietz explained. There is no box that DACA participants can check allowing the California Department of Health Care Services, which runs Medi-Cal, to identify applicants who are part of the deportation-relief program.

“The best estimate we have is from early to mid 2014, and it looks pretty low,” Dietz said.” Some of that is due to people not knowing [about Medi-Cal]. In early 2014, there were a lot of changes going on in the health care system and there was some confusion about eligibility.”

Dietz said it is important to get the word out that the original DACA program still exists. The Supreme Court’s decision is a missed opportunity, said Denisse Rojas, Dietz’ colleague and a beneficiary of the DACA program. Rojas is a medical student and cofounder of Pre-Health Dreamers, an information-sharing network for undocumented students pursuing careers in health care.

“There are great programs and assistance for [undocumented] youth,” she said, “but there is not much for adults, and there is an urgency for adults who are aging, especially those with chronic conditions.”

Rojas added: “Undocumented youth have been labeled as deserving and high achieving, and therefore have different points of access [to health care]. Meanwhile adults — our parents — have been blamed.”

Back in Canoga Park, Torres worries about her health, especially with her family history of diabetes. She only visits a doctor when she’s feeling very ill, she said. Preventive checkups are not a common practice for her.

Her husband, who works at a nursery, has coverage through his job. But they can’t afford the cost of adding her to his health plan. Their son is covered through Medi-Cal.

When she was pregnant, Torres bought health insurance. She had a high-risk pregnancy and figured that she’d receive better prenatal care by paying for her coverage, rather than receiving the free coverage offered through a limited-benefit version of Medi-Cal, which pregnant women may qualify for regardless of their immigration status.

“We were paying $400 a month,” Torres said. “We can’t always afford that.”

Torres volunteers with the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights of Los Angeles, an advocacy group, where she learned about access to health care through county-run programs. Some coverage is available to her in Los Angeles by a county-based health care program, but it’s not offered everywhere in the state. It is not available to someone living in nearby Kern County, for example.

She has also considered purchasing a health plan through Covered California, the state insurance exchange. Although the Affordable Care Act bars people living in the country illegally from buying policies on the exchanges, that might change in California.

California officials are asking the federal government for an exemption from that rule. If granted, California would become the first state to allow undocumented immigrants to buy health coverage on the exchange, which has caused controversy with opponents who argue California must address costs and other issues with its current health care system before growing the pool.

While access to the exchange could potentially help some, others like Torres wouldn’t be able to afford it without subsidies, she said.

Torres hopes the Supreme Court will ultimately overturn its decision, allowing her to get Medi-Cal through the DAPA program.

“We won’t give up,” Torres said. “And we can’t lose hope.”