As the Zika virus spreads both at home and abroad, new information is bringing to light how children — even those who at birth do not show obvious signs of impairment — are likely at a greater risk than previously believed.

This possibility, experts say, is highlighting a need to better track the development and well-being of babies who may have been exposed to the virus in utero.

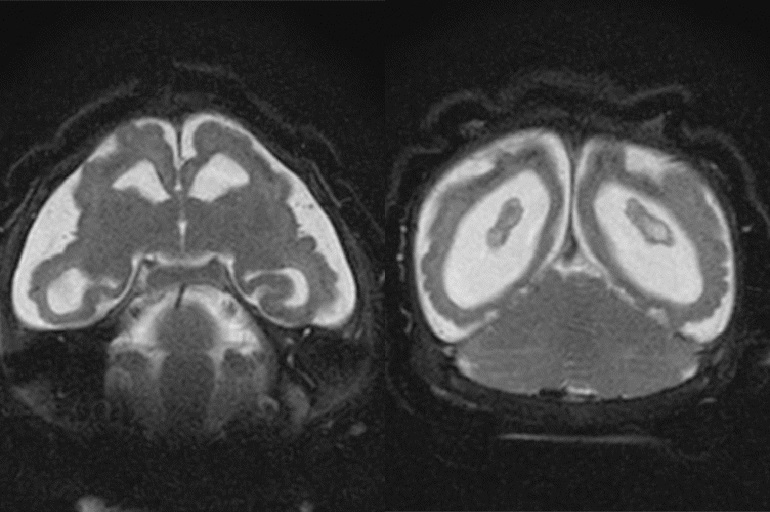

The development: Scientists in Brazil reported last week on an infant, whose mother contracted the virus late in pregnancy, which has typically been considered a less vulnerable time. The infant didn’t show signs of developmental problems but still had Zika in his urine, saliva and serum two months after being born. By six months, the child had begun showing signs of brain impairment — suggesting the virus can linger longer in babies’ systems and cause health problems later than previously believed.

The report only describes one case, which limits what scientists can reasonably conclude. But it underscores a need for better counseling, more thorough monitoring of children who were potentially exposed and increased research on how Zika may affect children, doctors said.

“There’s not that much long-term follow-up with the Zika infection. This provides insight into the fact that risk doesn’t disappear with delivery,” said Martha Rac, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at Texas Children’s Pavilion for Women and Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. “It changes how we need to counsel mothers.”

In a clinical guidance published before the Brazil report, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention called for regular assessments of children who may have been exposed in utero. Practically, that means tracking things like head size and how babies progress in terms of vision and hearing responses as well as their ability to feed.

The new development in some ways validates what public health experts have suspected, and stresses the need to follow through on tracking at-risk children and making sure they show healthy development, said Scott Needle, chief medical officer at Healthcare Network of Southwest Florida, in Naples, and a member of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Disaster Preparedness Advisory Council. It emphasizes, for instance, the importance of regular well-child visits and thorough communication between doctors and parents.

Surveillance of babies who may have been exposed is critical, added Mohan Pammi, medical director of the neonatal intensive care unit at Texas Children’s Pavilion for Women.

Doctors and parents alike, Needle added, need to be informed. What may look like a bad bout of colic could in fact indicate a more fundamental problem with brain development.

“Once the baby is born, [we need to] have them be monitored and followed, even if there’s no microcephaly,” said Peter Hotez, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, and an expert on the virus.

Therein lies another challenge. Many public health experts argue that lower-income people — who are less likely to have air conditioning, or live in the kind of housing that keeps mosquitoes away — are at a greater risk of coming into contact with Zika-bearing mosquitoes.

For those families, regular access to health care often poses a greater issue. It’s often much easier for children – 40 percent of whom nationwide are covered by Medicaid, the federal-state insurance plan for low-income people – than it is for adults, Needle noted.

But regular preventive medicine, which could be leveraged to do those screenings and assessments, is still no guarantee.

(Kevin Frayer/Getty Images)

Take well-child visits. Children are supposed to receive nine such visits in their first 15 months of life. But on average, about 40 percent of the children covered by Medicaid had fewer than six wellness visits in that timeframe, according to 2015 data from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. That builds on other reports suggesting that low-income children are less likely to receive preventive screenings and services.

“It’s not always easy for parents. There are always going to be opportunities for improvement,” Needle said. Gaps in access certainly persist, he added.

Meanwhile, pediatric specialists and experts who might know how to better navigate the disease and undermine its potential consequences aren’t always available, noted Nassim Zecavati, an assistant professor of pediatrics and neurology at Georgetown University School of Medicine in Washington, D.C.

“Those children, as they get older, are going to need a lot of services: rehab, early intervention, speech therapy,” she said. “It depends on where you live — what part of the country you live in — and how well served that population is.”

That matters. There’s no cure for Zika, and researchers still don’t fully understand all the ways it affects the brain. But, experts said, identifying brain problems early and addressing them as soon as possible can make a huge difference for children.

“You’re going to reduce the risk they get worse,” Needle said.

Without that focus, the potential consequences could be severe, he said. Treating neurological disorders can get expensive. Add depending on the severity, the price tag and emotional labor of caring for a child can take a toll on a family’s health, too.

Given the high number of children covered by public insurance programs, some of the long-term costs could end up in front of taxpayers, putting a strain on state budgets, he added.

Meanwhile, Zika still poses a moving target. As understanding of the virus continues to evolve, so do views on the threat it poses, and the right kind of intervention.

“The more we learn about this virus, the more we learn about how it affects the brain, and how it lingers,” Zecavati said. “It helps us know more about the virus, and how to treat the virus, and how to treat the children who are affected. Those children who have been affected are going to have significant long-term needs.”