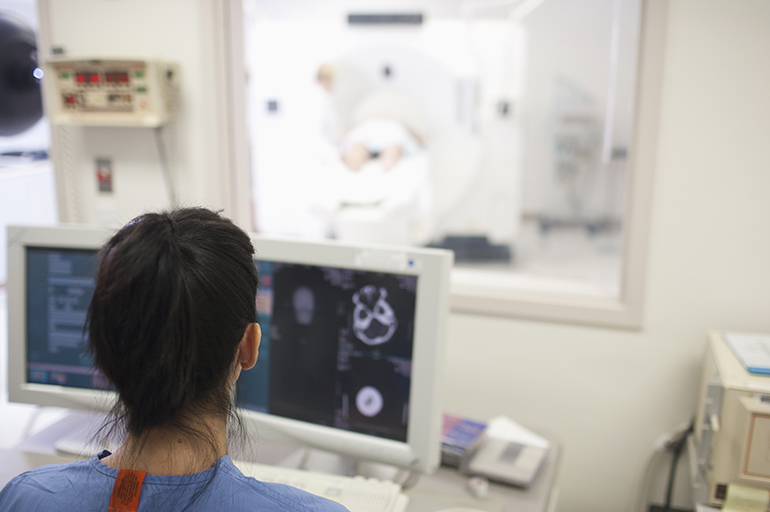

Narciso Lara, 36, was trying to support his family in Salinas as a forklift driver but didn’t see any opportunity for advancement. So last year, he enrolled in a community college program to become a radiologic technologist.

Now, Lara takes classes at Foothill College in Los Altos Hills, Calif., and gets hands-on training at a health clinic nearby. By the end of the 22-month program, he will have completed 1,850 clinical hours — all unpaid.

That could change under the terms of proposed state legislation that would require hospitals and clinics to pay minimum wage to Lara and other students who are completing the training hours necessary to become allied health professionals. The current minimum wage in California is $10.50 an hour for organizations with more than 25 employees, and it is scheduled to rise to $15 over the next five years.

The bill, AB 387, would cover an estimated 50,000 people training for jobs such as respiratory therapists, vocational nurses, dietitians and pharmacy technicians. It would not cover marriage and family therapists or psychologists.

The legislation, authored by state Assemblyman Tony Thurmond (D-Richmond) and sponsored by the powerful SEIU-United Healthcare Workers West union, would broaden the definition of “employer” to include hospitals and clinics that are supervising trainees in the allied health professions.

At the heart of the issue is whether the trainees should be considered students or employees. Perhaps counterintuitively, getting a paycheck could have unexpected consequences for the trainees.

Lara said he would love to be paid while going to school, because his wife, a dental therapist, is supporting him and their children right now. But he worries that if hospitals and clinics had to pay students, they might be less willing to offer them training slots, and then there would be nowhere to get the requisite clinical hours.

“If this bill passes, I don’t know what’s going to happen. It’s scary actually,” Lara said.

“If this bill passes, I don’t know what’s going to happen. It’s scary actually,” said Narciso Lara, 36, who is studying at the Foothill College Radiologic Technology Program. (Courtesy of Foothill College)

Supporters say the bill would make it easier for more low-income students and working adults to become allied health professionals. To get certified or licensed, students have to complete anywhere from 160 to 1,850 unpaid clinical hours. That may be an insurmountable barrier for many, according to SEIU-UHW, which represents about 37,000 allied health workers in California.

“We are really talking about choking off a lot of people getting into these jobs,” said Michael Borges, political coordinator for SEIU-UHW.

Borges also said the students deserve compensation for their work, which the union estimates is worth at least $200 million in wages each year. “These are real trainees doing real work that provides a real benefit for these sites,” he said.

But accrediting bodies and community colleges have expressed concern about the bill. One agency, the Joint Review Committee on Education in Radiologic Technology, wrote a letter to Assemblyman Thurmond saying that pay for students is “inconsistent” with its accreditation policies.

Hospitals argue that paying wages would be a financial burden for them, especially since they already fund and provide the training and supervision required. The California Hospital Association estimates that paying allied health trainees would cost anywhere from $1.5 million annually for small hospitals to $36 million for larger health systems. Statewide, that would likely add up to a lot more than what the union estimates.

“The ramifications are huge,” said Cathy Martin, vice president of workforce policy for the California Hospital Association.

In addition, the association argues that the trainees aren’t employees, but rather students who — by law — must be supervised by licensed health care workers.

“These are unlicensed individuals who cannot provide care to patients without direct supervision,” Martin said. “They are learning what they need to know to become that licensed professional.”

Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles would probably have to reduce its number of slots for such trainees were the bill to pass, the hospital’s CEO Thomas Priselac told Thurmond in a letter. Cedars would be required to pay the more than 220 occupational and physical therapists, laboratory scientists and others it trains each year. It would also have to provide them with workers’ compensation, health insurance and other employee benefits, Priselac noted.

“The effects of this significant decrease in capacity within the current training system would exacerbate existing allied health care workforce shortages and put the development of a strong and diverse pipeline of future caregivers in jeopardy,” Priselac wrote.

Rachelle Campbell, director of the Foothill College radiologic technology program that Lara attends, said that helping students financially is a great idea but that the proposed legislation would have too many negative impacts.

“If our hospitals have to pay our students, they are going to walk away,” she said. “All of our contracts say students are not employees.”

The Foothill College radiology technologist training program places students at Stanford Medical Center, Santa Clara Valley Medical Center and other hospitals and clinics in the Bay Area. The students are under one-on-one, direct supervision for their first three quarters. After that, they have slightly more autonomy, but the supervisor must be within earshot, Campbell said.

These are real trainees doing real work that provides a real benefit for these sites.

Another one of her students, Rick Li, said he had to take out a loan to go back to school. But he is convinced he will make that money back when he graduates. The San Jose resident said he knew from the outset that the unpaid clinical hours were part of becoming a radiologic technologist.

“We are not really working for free,” said Li, 29. “We are working for our education.”

Li said that as a student he can make mistakes and learn from them. “If we were making money, we would be seen as techs rather than students. And if we don’t perform an exam correctly, they are going to judge us more harshly,” he said.

But Mayte Paniagua, an SEIU member who supports the bill, said going back to school about 15 years ago to become a pharmacy technician was a huge burden. The single mother had to leave her paid clerical job to work the unpaid training hours.

“I ended up finishing my internship program, but unfortunately I went into debt,” she said. “It’s not fair for other people out there to struggle just to get a better-paying job in health care.”

Paniagua, who now works as a pharmacy tech at Pacifica Hospital of the Valley in Sun Valley, said there really isn’t much difference between being a trainee and an employee.

“Technically the [trainees] are working,” she said. “They are hands-on. That’s why these people should get paid.”

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.