Rachael Norman needed to submit a pile of out-of-network medical bills to her insurance company for reimbursement. Short on time, she started searching for a company that could do that tedious work for her.

She failed to find one, so she started one herself.

Norman said her company, Better, along with a handful of other Silicon Valley start-ups, is attempting to usher medical billing technology into the 21st century. Banking, transportation, furniture and grocery shopping can all be managed with some fancy finger work on smartphone screens. She and other entrepreneurs wondered: Why not medical bills?

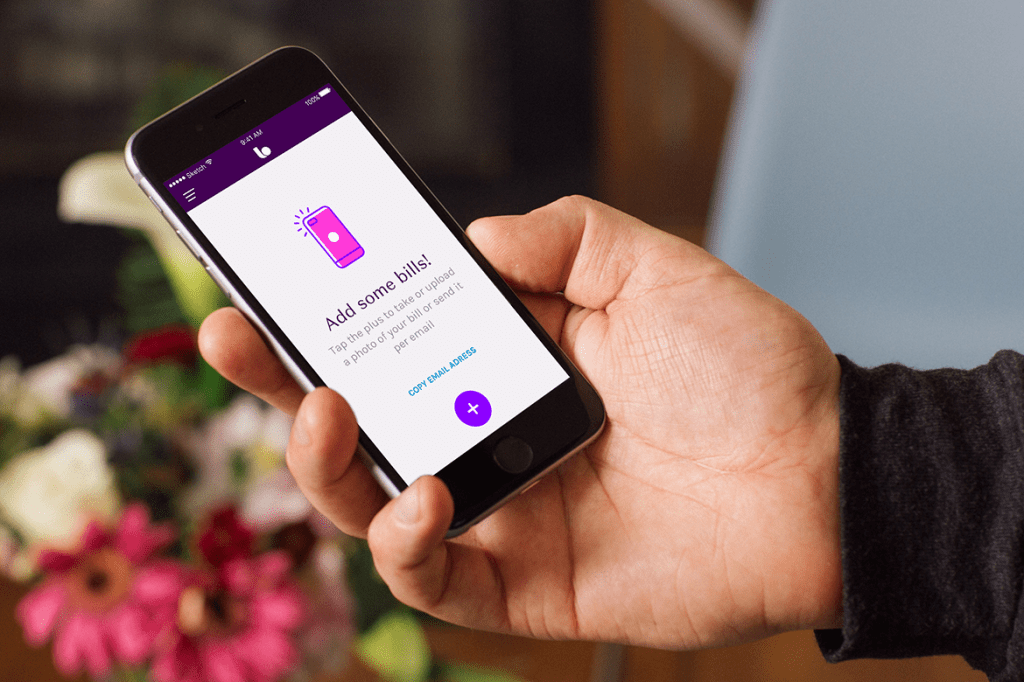

Today, Norman’s clients submit digital copies of their out-of-network bills through an app on their phones. Better’s employees navigate the bureaucratic thicket to track down reimbursements — and keep 10 percent of the money they recover from insurers.

The company has processed millions of dollars in claims, for everything from psychiatry to acupuncture to contact lenses, Norman said. The majority of Better’s customers have Preferred Provider Organizations (PPOs) or other types of insurance policies with out-of-network benefits. Unlike visiting in-network doctors, patients using out-of-network services often must pay upfront, then ask for reimbursement from their insurer later.

“For a lot of people, it becomes magic that we’re able to solve those problems and get them the money they are owed from insurance,” said Norman, who founded Oakland-based Better about a year and a half ago.

Better is among a new breed of start-ups trying to lead customers through the labyrinth of medical billing. Each has taken on a different aspect of billing — helping patients file claims, scanning bills for errors or making charges easier to understand.

But in their quest to revolutionize an industry, these start-ups face a variety of obstacles, including trouble getting access to medical records and difficulty cracking complex insurance policies. Some of the young companies are flourishing. Others are folding.

Pairing a technological solution with an industry that still uses faxes, distant call centers and snail-mailed bills can prove challenging. “You can’t automate repeated phone calls to a guy in a basement who doesn’t want to do his job,” said Victor Echevarria, whose company, Remedy Labs, folded two years after he founded it.

The emergence of these businesses reflects the fact that medical billing is a complicated, often byzantine process that can mystify even the savviest consumers. Adding insult, these bills often start to pile up while patients are still at their lowest — either dealing with serious medical issues, or just beginning to recover.

Kristin-Leigh Brezinski, who works for a small tech company in Seattle, said she started using Better to address a pile of therapy bills she’d been meaning to submit for reimbursement. She had put off the task partly because she knew it would be a headache to spend hours on interminable phone calls, she said.

“I didn’t really want to sit on hold for the rest of my life,” said Brezinski, 28. She liked Better’s service so much that she continues to use it and has recommended it to others.

Experts agree that consumers need help tackling costly and complicated medical bills.

“Medical problems and medical bills are very likely to be the straw that breaks the camel’s back of a family’s finances,” said Anthony Wright, executive director of Health Access California, a health care consumer advocacy organization.

Wright said the Affordable Care Act provided some protection for people, such as banning annual and lifetime limits on coverage and capping out-of-pocket maximums.

Many states, including California, have also adopted consumer protections against surprise medical bills. These are the often costly charges consumers receive from out-of-network providers, even though they went to an in-network facility.

Despite those advances, Wright said many aspects of medical billing remain a major problem for consumers. He thinks apps might help patients navigate certain issues, but policy fixes could be even more effective.

For example, an app could notify consumers when they’ve hit their annual out-of-pocket maximum, but the state could simply require insurers to provide that notice, negating the need for the app.

“I would love to put in place some laws and consumer protections that make some of these apps obsolete,” Wright said.

The landscape isn’t necessarily friendly to medical billing start-ups, as Echevarria discovered after he founded San Francisco-based Remedy Labs two years ago.

He was inspired to tackle the problem of medical overbilling after his infant son had to go to the emergency room for a fever-related seizure and his family incurred about $12,000 dollars in medical bills, many of them laced with errors.

Co-founder Marija Ringwelski had looked at her own bills and found errors about 80 percent of the time. The two decided to build a platform similar to Credit Karma, the popular credit and financial management platform that offers a free credit score and free credit monitoring. Only this one would be for medical bills.

“Everybody wanted that product,” Echevarria said. “They wanted the medical bill version of identity protection.”

Using new technology and a team of experts that scrutinized clients’ medical bills in search of errors, Remedy eventually figured out how to operate efficiently in all ways but one, Echevarria said: While patients had a legal right to their own medical information, many billing offices refused to hand it over to third parties.

“The industry operates in a way that is decades old,” he said. While a lot of the operation could be automated, some of it remains frustratingly hands-on and time-intensive, he said.

The problem proved insurmountable, and the company went out of business this past summer.

Even if companies manage to get their hands on required medical records, insurance policies are extremely complicated and can be difficult to navigate, said Betsy Imholz, special projects director for Consumers Union.

Rules vary among companies, and regulations among states, she said. To help an individual, companies must comb through piles of documents and figure out each customer’s specific situation. As Remedy’s experience illustrates, that process can’t always be accomplished with simple technology.

There’s also a marketing problem: Many consumers “don’t realize there’s help to be had,” said Mark Hall, director of the Health Law and Policy Program at Wake Forest University’s School of Law.

Palo Alto-based Simplee addressed some of these challenges by shifting its business model.

Rather than directly serving consumers — as it did when it was a new start-up seven years ago — Simplee now markets its software to hospitals. Its clients currently include more than 400 hospitals and more than 2,000 clinics.

The software gives patients access to all of their bills in one place and attempts to make charges easier for them to understand. It also allows patients to see detailed explanations of charges and to create payment plans when necessary, said John Adractas, the company’s chief commercial officer.

“It’s not like there’s one formula for how to tackle health care problems,” Adractas said.