Cyndee Weston can barely remember the last time she didn’t have to switch health plans during an Affordable Care Act sign-up season. By her count, she has been on five plans in five years.

Every fall, after she has spent months figuring out her insurance plan’s deductibles, doctor networks, list of covered drugs and other fine print, she receives notice that the policy will be canceled as of Dec. 31. Because her job doesn’t come with insurance, “it’s agonizing going through all the plans and trying to compare,” said Weston, 55, who has diabetes and a history of melanoma. “Every year it’s the same scenario: ‘We’re not going to renew your policy.’”

Under the market-based system set up by the ACA, individuals are encouraged to “shop around” each year to find insurance that better suits medical needs and income. In fact — like Weston, a trade association executive in Sulphur, Okla. — they are often forced to do so when plans drop out of the local market or eliminate preferred hospitals and doctors from the network.

The ACA increased the number of Americans with health insurance by 20 million and cut the uninsured rate to about 9 percent.

But the task of finding new insurance annually often undermines the continuity of care for people with ongoing medical needs or chronic conditions. That challenge is immeasurably harder this year as policies change under the Trump administration, spurring unstable networks and turmoil in many state and local markets.

“There’s quite a number of people who are either temporarily uninsured or they move into different plans” each year, said Marianne Udow-Phillips, head of the Center for Healthcare Research & Transformation at the University of Michigan. “And I’m guessing this year that will be much greater, given all the changes that are happening in the marketplace plans.”

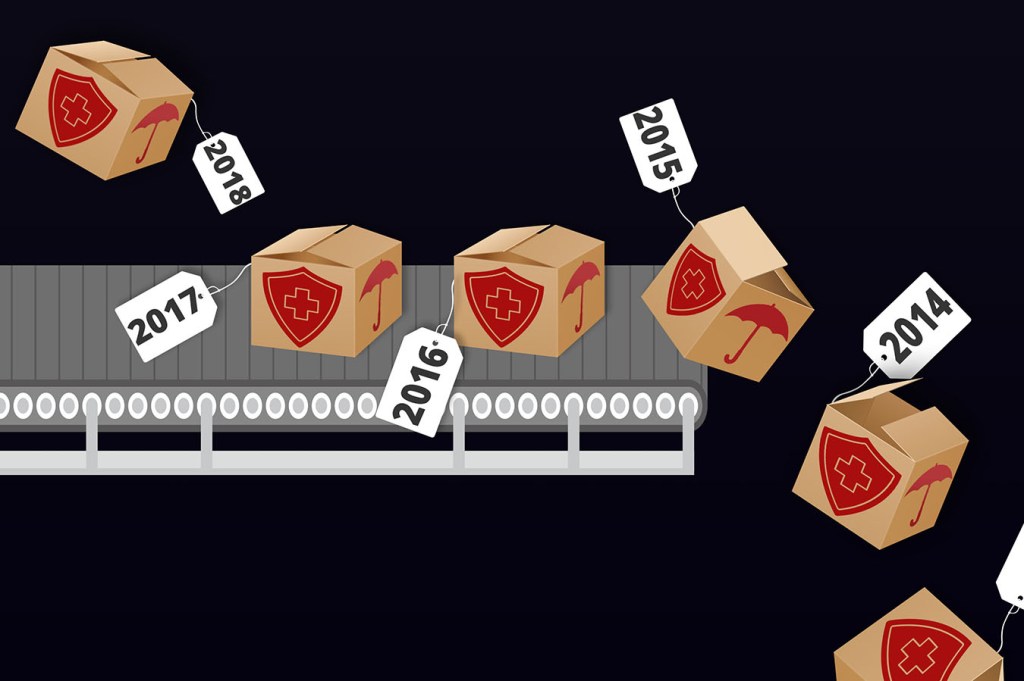

Fewer than half of those buying individual coverage in 2014 kept the same plan the following year, according to a Michigan survey done by Udow-Phillips and colleagues. Nearly a third of marketplace enrollees for 2017 were new customers, meaning they had other kinds of coverage before or were uninsured. For the 2018 enrollment season that began on Nov. 1 and ends Dec. 15 in most states, millions of consumers will find themselves switching coverage.

The imperative to shop for insurance affects mostly those who buy insurance for themselves, such as small-business owners and those who are self-employed.

Enrollment for 2018 through online ACA marketplaces has been particularly complicated, due to big premium increases for some plans, the mistaken belief that the health law was fully or partially repealed and the administration’s decision to terminate $7 billion in subsidies.

Many of plans that people relied on for 2017 are being canceled, the result of insurers exiting the marketplaces or redesigning coverage to try to keep premiums down.

Aetna and Humana stopped selling individual marketplace plans for 2018 after losing money on the products. UnitedHealthcare has sharply pulled back. Hundreds of counties have only one marketplace insurer next year, although competition is higher in metro areas.

The average number of carriers selling individual marketplace plans in each state has fallen from five in 2014 to 3.5 next year.

“I wouldn’t call it ideal. It’s what we have,” said Sabrina Corlette, who studies insurance for Georgetown University’s Health Policy Institute. “Ultimately, the consumers have to read the fine print and probably expect that things are going to change from year to year.”

Such instability impedes what was supposed to be the ACA’s other big goal besides coverage expansion. Former President Barack Obama talked of fixing a “broken system” that neglects preventive care, orders billions of dollars in unneeded procedures and shuffles patients among doctors who don’t talk to each other.

The idea was to push insurers to help diabetics improve diets, keep patients on their blood-pressure medication, prevent asthma flare-ups and otherwise improve care and control costs.

Investing in prevention upfront, the thinking went, would pay off for carriers over time as members needed less emergency and inpatient care.

That equation fails when people find themselves with a new policy or a new insurance company each year — or more often.

Insurance churn “is a long-standing problem in the U.S. health care system,” said Benjamin Sommers, a physician and health economist at Harvard’s Chan School of Public Health.

“But there’s a concern that with the ACA you’ve added a whole new layer.” Insurance turnover is especially frequent among lower-income families and those with irregular work.

Unemployed people might be eligible for a plan under Medicaid, which the ACA expanded to most low-income adults in most states. But getting a job and a salary might make them ineligible for Medicaid, bumping them up to a subsidized marketplace plan and a coverage change.

Medicaid, which often comes with its own confusing menu of managed-care plans, generally covers those with the lowest incomes. Subsidized marketplace plans are for medium-income households.

In a 2015 survey by Sommers and colleagues, about a fourth of low-income adults reported they changed coverage during the previous 12 months. That was lower than expected but still problematic, Sommers said.

More than half the switchers had coverage gaps between policies, causing many to report skipped medications and poorer health. Even plan changers with no coverage gap were more likely to swap doctors, to have trouble booking appointments and to seek treatment in the emergency room.

Even though laws in some states allow patients in active treatment to keep doctors from one plan to the next, that’s not a recipe for stable medical relationships or long-term treatment strategies.

“Coming up with the right balance and right approach to a patient’s condition takes time,” said Sommers. “If you wind up with a new set of doctors and new coverage every year, it’s going to make that much harder.”

Cyndee Weston has navigated the shifting ground better than many. For years she has had the same insurer — BlueCross BlueShield of Oklahoma — which has dominated that state’s market for individual plans and is the only marketplace player for 2018.

But even though the carrier is the same and the health law requires insurers to take all comers, canceled plans each year force her to learn a new coverage design, file new paperwork with doctors and worry her primary physician will be dropped from the network.

One year BlueCross “automatically enrolled us into a bronze plan which we didn’t want, so we chose another gold plan,” Weston said.

Even when insurers stay in a particular market, they often redesign plans from year to year, changing drug coverage or raising out-of-pocket costs to keep premiums as low as possible, Corlette said. As in Weston’s case, that often requires canceling the old plan and having subscribers switch.

“Each year, we assess our plan offerings and make any necessary adjustments to best meet our members’ anticipated health care needs,” BlueCross Oklahoma spokeswoman Melissa Clark said via email.

After Weston’s primary physician left the plan’s network this year, she’s had trouble finding a new one, although the insurer said its physician list has not changed significantly.

“I take some medications, and I worry that if I go to a new doctor they’ll change my medication or it won’t be covered,” she said.

A few weeks ago, she got a new notice from BlueCross saying her current plan is canceled as of Dec. 31. So she’s shopping again.

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.