Three Tuesdays each month, Katherine O’Brien straps on her face mask and journeys about half an hour by Metra rail to Northwestern University’s Lurie Cancer Center.

What were once packed train cars rolling into Chicago are now eerily empty, as those usually commuting to towering skyscrapers weather the pandemic from home. But for O’Brien, the excursion is mandatory. She’s one of millions of Americans battling cancer and depends on chemotherapy to treat the breast cancer that has spread to her bones and liver.

“I was nervous at first about having to go downtown for my treatment,” said O’Brien, who lives in a suburb, La Grange, and worries about contracting the coronavirus. “Family and friends have offered to drive me, but I want to minimize everyone’s exposure.”

While her treatment hasn’t changed since the novel coronavirus spread across the United States, the 54-year-old is at high risk of severe complications should she become infected. Those risks haven’t declined significantly for her despite the Illinois governor’s loosening of COVID-related restrictions.

She’s not alone in fearing the deadly combination of COVID-19 and cancer. One study, which reviewed records of more than 1,000 adult cancer patients who had tested positive for COVID-19, found that 13% had died. That’s compared with the overall U.S. mortality rate of 5.9%, according to Johns Hopkins.

Beyond the concern of cancer patients — with their already depleted immune systems — catching the virus, many doctors worry about people delaying their scans and checkups and missing time-sensitive diagnoses. A KFF poll found that nearly half of Americans had skipped or postponed medical care because of the outbreak. Cancer patients seeking care face an array of obstacles as states reopen, such as heavily restricted in-hospital appointments and new clinical trials on hold. (KHN is an editorially independent program of KFF, the Kaiser Family Foundation.)

“Cancer doesn’t care that there’s a coronavirus pandemic taking place,” said Dr. Robert Figlin, chair in hematology-oncology at Cedars-Sinai in Los Angeles. “We don’t want people who have abnormalities to delay having them evaluated.”

While tending to her own breast cancer, Megan-Claire Chase takes her mother to regular treatments for blood cancer at Northside Hospital Forsyth in Cumming, Georgia. As the caregiver, Chase is given a green wristband and cleared to go in. (Courtesy of Megan-Claire Chase)

In late March, Megan-Claire Chase, 43, of Dunwoody, Georgia, got laid off from her job as a project manager for a staffing company, losing the health care benefits that came with it. Her chief concern was paying for a diagnostic mammogram and MRI, still on the calendar for two days before her benefits were to end. Currently in remission from stage 2A breast cancer, Chase schedules scans for every six months well in advance at Breast Care Specialists in Atlanta.

“When I got there, it was really unsettling. You almost feel like a leper,” said Chase, noting the socially distanced waiting room and heavily sanitized clipboards. Already hyper-careful since her days of chemotherapy, Chase carries her own pens in her purse, along with gloves and extra masks.

Cancer centers across the country are taking extra precautions. At Northwestern, patients are funneled through a single entryway, where masks are required, and are met by a security guard and a temperature check before signing in with receptionists seated behind plastic shields, O’Brien said. No visitors or accompanying family members are allowed inside the building, and the cafeteria and waiting rooms are devoid of unnecessary germ-spreading agents — no magazines or coffee machine in sight. The cubicle where she receives infusions of Abraxane used to seat four patients; now, only two sit in the space.

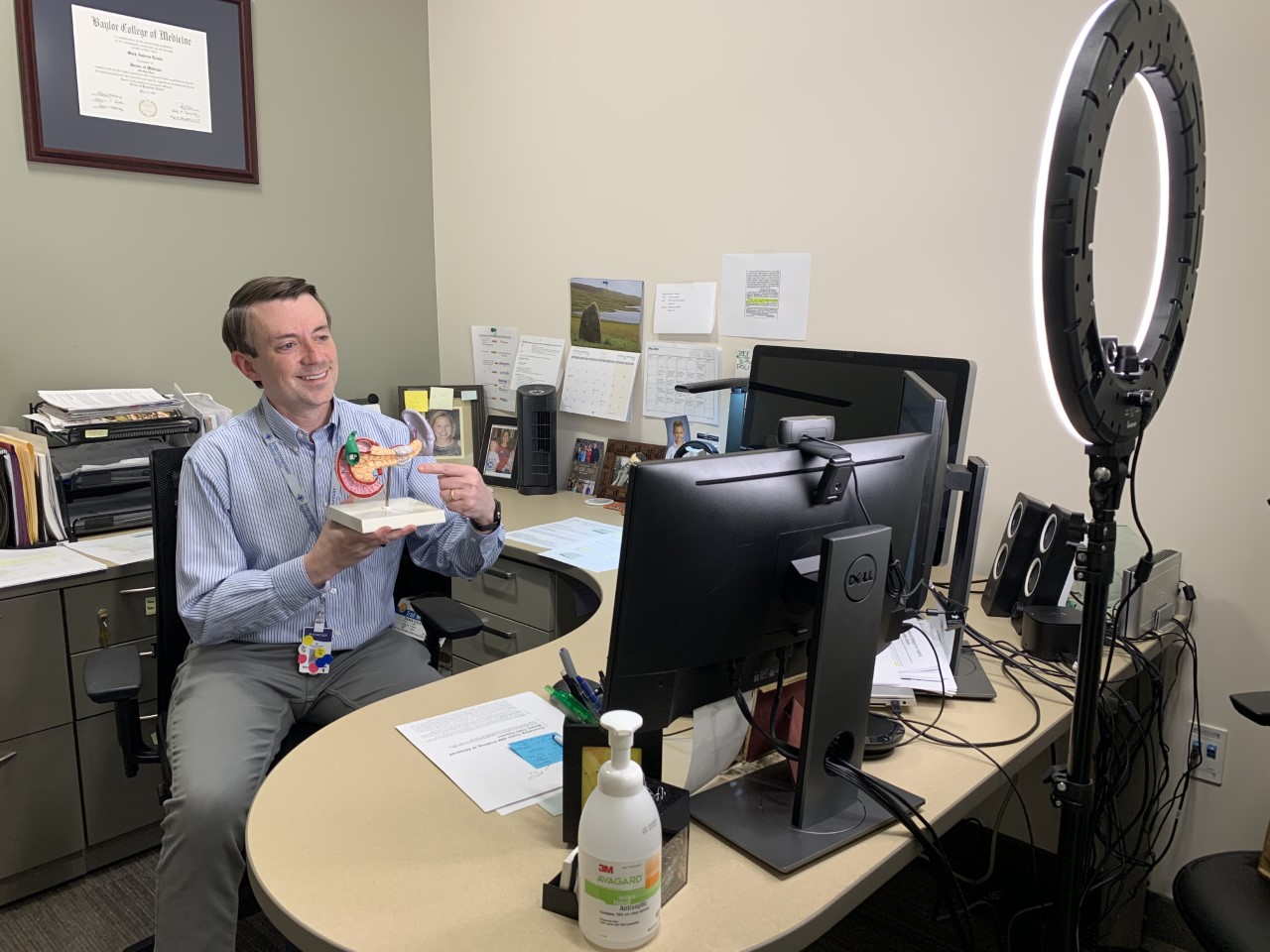

Dr. Mark Lewis, director of gastrointestinal oncology for Intermountain Healthcare, explains pancreatic cancer to a telehealth patient. (Courtesy of Dr. Mark Lewis)

Where they can, many doctors are turning to telemedicine to limit cancer patients’ trips to the hospital. In Salt Lake City, Dr. Mark Lewis, director of gastrointestinal oncology for Intermountain Healthcare, a 23-hospital system serving Utah and surrounding states, says about half his patient visits are now virtual. He’s also making some patients’ treatments less intense and less frequent. As at Northwestern, patients must arrive at the hospital solo for appointments unless assistance is physically necessary. It’s a significant shift for Lewis, who’s had up to 30 family members in his office for appointments alongside his patients for mental support.

“We are writing the rules as we go, trying to keep patients’ immune systems up and the cancer at bay,” said Lewis. Still, he’s concerned about a later spike in cancer mortality due to the coronavirus pandemic. The coronavirus aside, the National Cancer Institute estimates over 600,000 Americans will die of cancer this year.

New clinical trials have also largely ground to a halt in this new era, when traveling long distances for treatment is less of an option. Linnea Olson, who lives in Amesbury, Massachusetts, and has stage 4 lung cancer, worries there may be far fewer treatment options for her, as trials have been her “lifeline.”

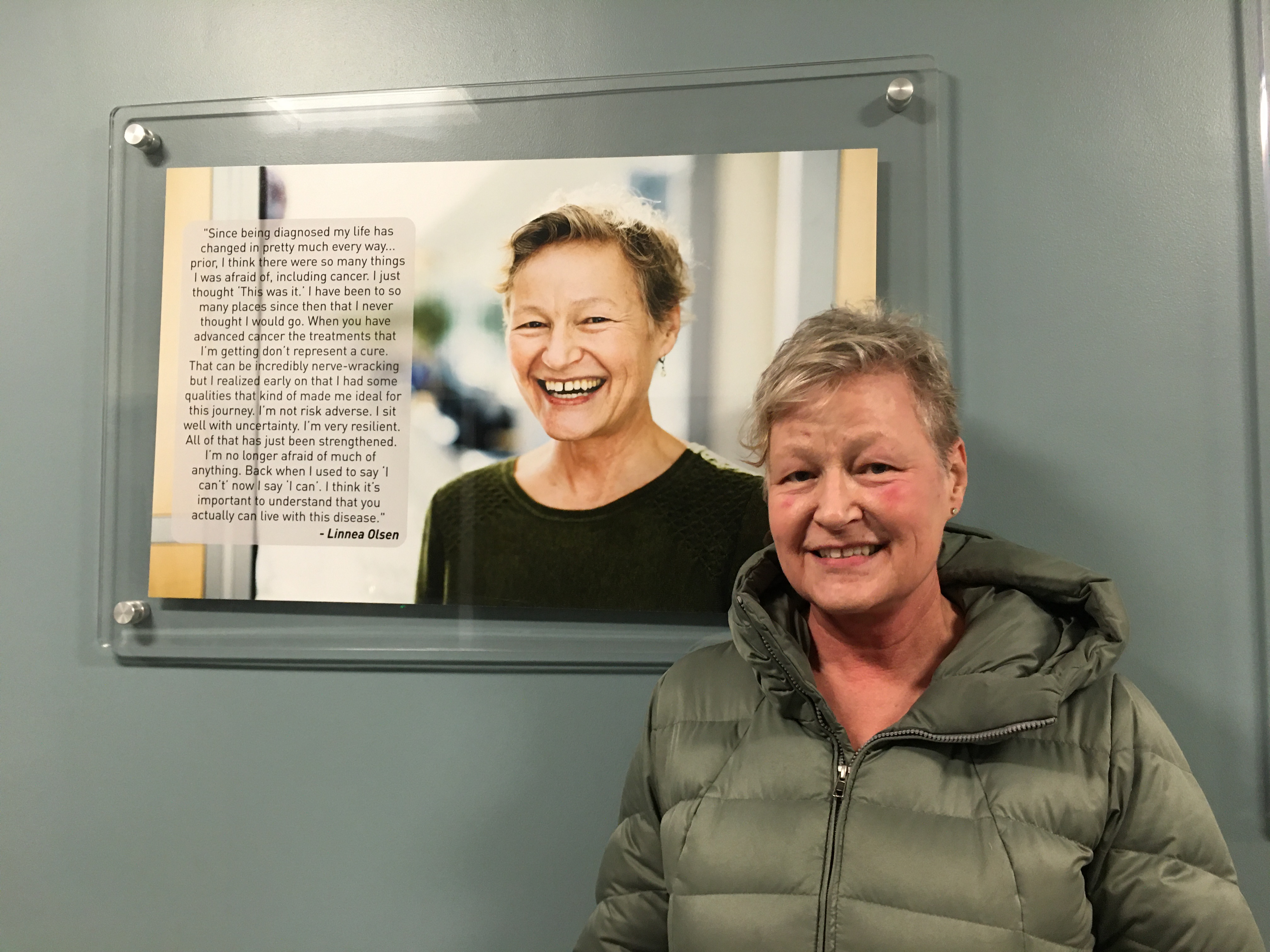

Linnea Olson stands in front of a photo of herself on the “wall of hope” at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. (Courtesy of Linnea Olson)

About four months ago, Olson, 60, enrolled in her fourth phase 1 clinical trial at Massachusetts General Hospital’s Termeer Center for Targeted Therapies. The treatment has been accompanied by intense side effects, such as a sore mouth and throat from mucositis, also a sign of COVID-19. Before a recent infusion, nurses with plastic shields ferried Olson up a back entryway for a COVID test. It was negative.

The intensity of her treatment, coupled with the extreme social distancing measures, has left Olson, who lives alone, feeling depressed and unsure if she should continue the trial.

“It’s too much all at once — the isolation and the difficult side effects,” Olson said.

Rudy Fischmann goes on a daily walk around his Knoxville, Tennessee, neighborhood past a colorful home decorated in chalk. (Courtesy of Rudy Fischmann)

The strolls are critical for working on his balance issues stemming from brain cancer. (Courtesy of Rudy Fischmann)

Rudy Fischmann, a brain cancer patient and former true crime TV producer, battles balance issues that started after his first set of surgeries two years ago. Daily walks and physical therapy are part of his treatment regimen. Yet strolls around his Knoxville, Tennessee, neighborhood are already becoming more stressful as the state begins to open up.

“It’s getting harder and harder, with more and more people outside every day,” said Fischmann, 48. “I don’t enjoy walking laps around my kitchen, so I’m finding myself having to change my routes almost daily.”

A father of two young children who are now home round-the-clock, Fischmann finds all the family time draining his limited energy. He also fears what germs they will bring back from school come fall.

“The thought of, if I were to contract the virus, would I get a different standard of care?” he said. “I’m used to staying home and not doing that much, but it’s more nerve-wracking now.”

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.