When Joe Prude called Rochester, New York, police to report his brother missing, he was struggling to understand why Daniel Prude had been released from the hospital hours earlier. Joe Prude described his brother’s suicidal behavior.

“He jumped 21 stairs down to my basement, headfirst,” Joe said in a video recorded by the responding officer’s body camera in the early hours of March 23. Joe’s wife, Valerie, described Daniel nearly jumping in front of a train on the tracks that run behind their house the previous day.

“The train missed him by this much,” Joe said, holding his thumb and pointer finger a few inches apart.

“When the doctor called me and told me that they released him, I’m saying, ‘How you going to sit here and tell me you’re going to release him when he was hurting himself? Come on. You weren’t sworn to do that,’” he said on the body camera footage.

At the point of this recorded conversation just after 3 a.m., Joe and Valerie Prude knew only that Daniel was missing, delusional and vulnerable. They didn’t know his next encounter with the police would be fatal.

Police would find Daniel minutes later ― naked, acting irrationally. Because he spat in the direction of officers and allegedly said he had the novel coronavirus, officers placed a white hood, called a “spit hood,” over his head. When he started trying to stand up, despite being restrained by handcuffs, an officer placed much of his body weight over Daniel’s head and pushed it into the pavement.

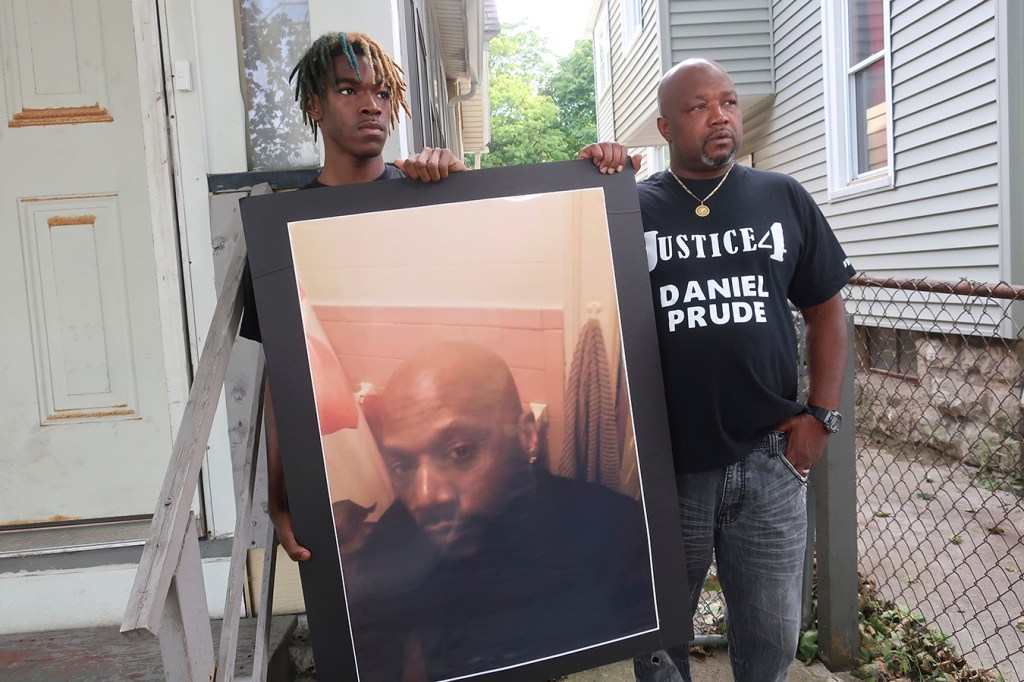

Daniel died a week later when his family took him off life support. The county medical examiner’s autopsy described his death as a homicide and listed the immediate cause of death as “complications of asphyxia in the setting of physical restraint.” The incident garnered widespread attention as another example of a Black man killed after an encounter with police.

Less attention has been paid to what happened to Daniel Prude in the preceding hours, when he was treated and released after a psychiatric assessment at Strong Memorial Hospital, run by the University of Rochester Medical Center.

Joe Prude called police at about 7 p.m. on March 22 because he needed help getting Daniel to the hospital. Daniel had been having problems with a PCP addiction, Joe told officers. Now he had begun telling Joe and Valerie that people were out to get him, and he wanted to die.

By about 11 p.m., Daniel was released from the hospital, according to Joe and police records. “He was calm as hell when he got back here,” Joe told police.

That didn’t last.

“He was fine for a little bit, then all of a sudden started acting crazy,” Joe said. He told police that Daniel asked him for a cigarette, and when he went to get one, Daniel took off running. He was barefoot, wearing only a tank top and long johns in 30-degree weather.

“He was gone. Track star status. Hauled ass like Carl Lewis,” Joe told

Around 3 a.m. the next day, four hours after his release from the hospital, emergency dispatchers started fielding calls about Daniel Prude. His brother reported him missing, and a tow truck driver spotted him, naked and bloodied, on West Main Street, police records show.

Police body camera footage shows that by 3:20 a.m., officer Mark Vaughn was pressing Daniel Prude’s head into the pavement.

While restrained, Prude stopped breathing. An ambulance crew resuscitated him, but he was in critical condition. His brain was damaged after being deprived of oxygen. He died a week later at Strong Memorial after being taken off life support.

The University of Rochester Medical Center said patient privacy laws bar it from discussing the specifics of Prude’s treatment and release, but, in general terms, spokesperson Chip Partner said, the hospital is bound by a New York state law that requires patients to be released within 24 hours unless they have a mental illness that is likely to result in serious harm to themselves or others and that requires immediate observation, care and hospital treatment.

The details of Prude’s encounters with law enforcement and the health care system offer a look into the practice of emergency psychiatry, and how, as in many branches of medicine in the U.S., mistakes in that field are disproportionately borne by Black people.

Medical decisions in a case like Daniel Prude’s are high-stakes, with little margin for error, said Dr. Ken Duckworth, chief medical officer of the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

“Emergency psychiatric assessment is very challenging, and the potential for catastrophic outcomes following your decision is very real,” he said.

The hospital where Prude died has faced scrutiny over its treatment of psychiatric patients and discharge procedures before.

In April 2018, federal inspectors found security officers at the hospital had used law enforcement restraint techniques against a pediatric psychiatry patient, breaking her arm and sending her to the emergency room.

Months later, inspectors found the hospital discharged a patient who was in the emergency room with a history of dementia and multiple medical problems despite a discrepancy in her address between her medical record and the information she gave hospital staff.

Two years earlier, inspectors found that hospital staff had placed patients in ankle and wrist restraints without an order to do so, and placed another patient in restraints without documenting when the restraints were released. Restraints are meant to be used only with a physician’s order, and federal rules require precise documentation of their use.

None of these incidents at Strong Memorial Hospital garnered media attention at the time they happened or at the time the reports were made public.

Strong spokesperson Partner said that immediately after the April 2018 inspection the hospital changed its public safety protocol to eliminate the use of law enforcement techniques to manage a violent patient unless that patient is being arrested.

He said updated staff training and discharge protocol after these incidents now mitigates the risk of discharging someone who was not ready to be released. “These protocols were well established in 2020 and had absolutely no bearing on the evaluation or treatment of Daniel Prude on March 22,” Partner said.

Prude’s case is unusual because the consequences of the decision by doctors to release him have played out so publicly, said Duckworth. Usually, emergency room psychiatrists never find out what happened to their patients.

“You make a very big decision, which usually has no known outcome. You put this person in the hospital, you go on to the next patient. You send this person home, you go on to the next patient,” he said.

Duckworth said he would not second-guess the actions of Prude’s hospital team in the moment, but with the benefit of hindsight, “there’s overwhelming evidence that he had a psychotic illness and was quite vulnerable,” he said. “He didn’t need to die.”

In a statement, URMC said its treatment of Prude was “medically appropriate and compassionate.”

Several oversight organizations are investigating.

The Joint Commission, which certifies hospitals to receive federal funding, said it’s reviewing Prude’s treatment at Strong. New York state’s Justice Center is investigating on behalf of the state Office of Mental Health.

The university medical center itself is still conducting an internal clinical review.

In response to questions from NPR and KHN about whether the hospital’s treatment of Prude could have been affected by his race, Partner said the medical center asked Dr. Altha Stewart, past president of the American Psychiatric Association, “to conduct a third-party independent review through her lens as a national expert on racism and bias in psychiatric care.”

In a separate interview before the request from URMC, she described how unconscious bias can cloud clinicians’ judgment and make it difficult for them to make the best possible decisions for their patients.

“It is very clear that in today’s health care system, bias is built in structurally,” Stewart said. “Seeing a tall, imposing Black man who is behaving aggressively puts in place a series of ideas and thoughts and assumptions that direct decision-making.”

Psychiatric disorders in Black patients are less likely to be taken seriously than in white patients, Stewart said. Unequal treatment starts early.

Black boys are viewed as adults more often than white boys of the same age, said Stewart, who is also the director of the Center for Health in Justice Involved Youth.

“So a Black child with a meltdown is described as aggressive, obstinate, oppositional,” she said, “as opposed to traumatized, depressed, anxious.”

Those expectations follow Black boys through adulthood and in the health care system, increasing the odds that doctors will view Black men as a lost cause and provide subpar care, Stewart said.

She stressed that she does not have any direct knowledge of deficiencies in the care of Daniel Prude, but she said that Black men, like Prude, are disproportionately likely to be misdiagnosed, mistreated and written off as a result of structural bias and unconscious racism.

A group of medical students at the University of Rochester wrote in an open letter that Daniel Prude was “sentenced to death by our failed healthcare system.”

“Not only do our current models of healthcare leave gaping holes for individuals such as Daniel to fall through, but they do so in manners which are fraught with racism,” the students wrote.

Partner, the medical center spokesperson, said the psychiatry department’s Office of Diversity, Inclusion, Culture and Equity will evaluate Daniel’s treatment for potential bias. He said the medical center “recognizes that we have a long way to go before we can confidently say that our policies and practices are universally culturally appropriate to the populations we serve.”

Both Stewart and Duckworth said reducing the role that police play in addressing mental health crises would increase the odds of survival for a person released too early from psychiatric care.

Federal inspection reports show that hospitals across the country have released patients who, like Prude, ended up in grave danger only shortly thereafter.

In March 2018, a patient with a history of schizophrenia, post-traumatic stress disorder and suicide attempts arrived at Russell County Hospital in Kentucky complaining of alcohol withdrawal, depression, anxiety and pain. An hour and a half later, the patient was discharged with instructions to “follow up with his/her primary care provider and take medications as prescribed.” Two hours later, the patient was back in the same hospital. A physician’s notes said the patient had drunk a bottle of Benadryl “in effort to kill self.”

In August 2018, federal inspectors found that UT Health East Texas Pittsburg Hospital discharged a patient who had verbalized a plan for suicide. The patient got a ride to his truck from the county sheriff. Later that day, the patient was found dead in the truck from a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

Last summer at Stafford County Hospital in Kansas, a patient arrived in the emergency room saying she had drunk half a liter of vodka because she was upset and wanted to die. She told hospital staff that she started drinking that day after two years of sobriety and that she “did not feel safe to go home due to the presence of alcohol.” The hospital discharged her 11 minutes later.

Earlier this year, inspectors found that a patient with a history of psychosis went to the emergency room at Mercy Hospital in St. Louis and told staff she needed to get back on her medication. She was delusional, disoriented, homeless and unable to give her name. She was discharged with a voucher for cab fare but no follow-up appointments or services and no plan to ensure she got her medication.

A spokesperson for UT Health East Texas said the health system has since implemented a process for staff to more thoroughly document mental health concerns in patient records. Mercy Hospital in St. Louis said it takes the health and safety of each patient very seriously “regardless of race, ethnicity or ability to pay.”

Neither of the other hospitals responded to emails or calls seeking comment.

This story is part of a partnership between NPR and KHN, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.