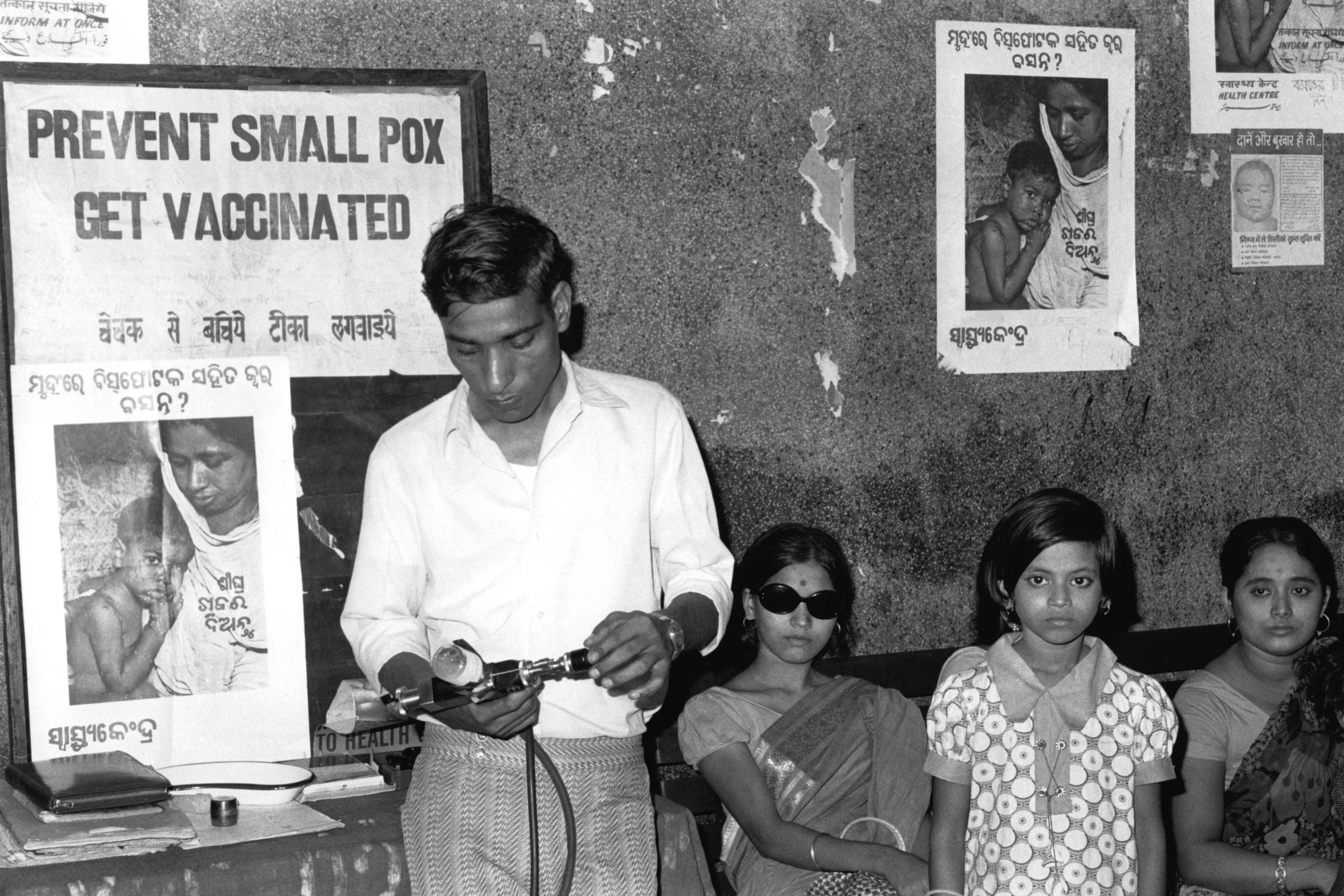

In 1973, Bhakti Dastane arrived in Bihar, India, to join the smallpox eradication campaign. She was a year out of medical school and had never cared for anyone with the virus. She believed she was offering something miraculous, saving people from a deadly disease. But some locals did not see it that way.

Episode 3 of “Eradicating Smallpox” explores what happened when public health workers — driven by the motto “zero pox!” — encountered hesitation. These anti-smallpox warriors wanted to achieve 100% vaccination, and they wanted to get there fast. Fueled by that urgency, their tactics were sometimes aggressive — and sometimes, crossed the line.

“I learned about being overzealous and not treating people with respect,” said Steve Jones, another eradication worker based in Bihar in the early ’70s.

To close out the episode, host Céline Gounder speaks with NAACP health researcher Sandhya Kajeepeta about the reverberations of using coercion to achieve public health goals. Kajeepeta’s work documents inequities in the enforcement of covid-19 mandates in New York City.

The Host:

In Conversation with Céline Gounder:

Voices from the Episode:

Podcast Transcript

Epidemic: “Eradicating Smallpox”

Season 2, Episode 3: Zero Pox!

Air date: Aug. 15, 2023

Editor’s note: If you are able, we encourage you to listen to the audio of “Epidemic,” which includes emotion and emphasis not found in the transcript. This transcript, generated using transcription software, has been edited for style and clarity. Please use the transcript as a tool but check the corresponding audio before quoting the podcast.

TRANSCRIPT

Céline Gounder:

When the World Health Organization set out to eradicate smallpox, enthusiastic young doctors and public health workers from all over the world showed up and spread out across the Indian subcontinent.

We had the chance to speak with some of them …

[Music begins]

Yogesh Parashar:

People never believed that the world would be free of smallpox, especially India.

Larry Brilliant:

There’s no reason to believe you could cure it.

Alan Schnur:

This is a terrible disease.

Bill Foege:

I was struck immediately by the smell. It was similar to a dead body.

Yogesh Parashar:

Any outbreak was an emergency.

Bhakti Dastane:

That itself was motivation for us.

Chandrakant Pandav:

I said, this is the time to serve my India.

Larry Brilliant:

We all seemed so confident that we could do it.

Alan Schnur:

That kept all of us in smallpox eradication working long hours under rigorous conditions.

Chandrakant Pandav:

It had to be done.

Hardayal Singh:

Our duty was to vaccinate each and every person by hook and by crook.

[Music fades out]

Céline Gounder:

By hook or by crook, vaccinate everyone. These smallpox eradication workers had a shared sense of duty. And they had a slogan: “zero pox!”

Bhakti Dastane:

We have to achieve zero pox, so it was our motto: zero pox.

Céline Gounder:

That refrain … it became a way for workers to greet one another, even replacing the usual hellos. It was a constant reminder of their shared goal.

Rajendra Deodhar:

Whenever one Jeep crosses the other, we used to greet one another as “zero pox.”

Céline Gounder:

You’ve just heard the voices of Alan Schnur and Drs. Yogesh Parashar, Larry Brilliant, Bhakti Dastane, Bill Foege, Chandrakant Pandav, Hardayal Singh, and Rajendra Deodhar. We’ll be hearing more from each of them throughout this podcast season.

So, this group of former eradication workers are grayer now. They’re mostly in their 70s. But you can still hear the youthful enthusiasm in their voices. You can feel that sense of purpose.

This episode is about what happened when this zealous bunch encountered hesitation.

Well, actually more than hesitation … real, everyday people, right in front of them, who were skeptical of the vaccine.

And just how far would the eradication workers go to stop smallpox?

I’m Dr. Céline Gounder, and this is “Epidemic.”

[“Epidemic” theme music]

Céline Gounder:

By the early ’70s, smallpox was coming under control in most of the world. But in India, the disease remained stubbornly entrenched in several areas, including the state of Bihar — in the East.

In some pockets of the region, a lot of people were skeptical about getting the vaccination.

The eradication program sent in a stream of dedicated smallpox workers — on bicycles and in 4×4 trucks — to prowl the countryside and cities.

Bhakti Dastane was among them.

Bhakti Dastane:

I’m Dr. Dastane, so I’m a gynecologist and I went to this, uh, WHO [World Health Organization] program, smallpox eradication program, when I was an intern.

Céline Gounder:

Bhakti answered the call in 1973. She was a year out of medical school, maybe 27 or 28 years old, and had never cared for anyone with smallpox. She had never even seen an actual smallpox case before.

But she was inspired to help and, when she arrived in Bihar, the program coordinators were surprised to see her.

They had been expecting a man. Bhakti and another female physician showed up instead.

[Music starts]

Bhakti Dastane:

We were only two lady doctors on that program, the smallpox eradication program. So we have to show them that ladies also can do as good as the gents.

Céline Gounder:

Proving they were “as good as the gents” in almost every situation — that was their first task, the thing they had to do before they could get down to the work of finding patients.

Bhakti and a team of about six to eight volunteers went house to house lugging vaccination kits, searching for people with smallpox and anyone they could vaccinate.

Mostly, the men of the household didn’t even want to talk to a female doctor.

Bhakti Dastane:

This thing was very new for them, for any female to go and talk to the male people in the house. They don’t give the importance to the female. So they don’t open up and don’t share the things with you. So, it took some time to develop this, uh, trust in them.

[Music ends]

Céline Gounder:

In Bhakti’s mind, she was offering health to the people of Bihar, saving them from a deadly disease.

But locals didn’t really see it that way.

Some believed that if they accepted the vaccine, they would anger the Hindu goddess Shitala Mata, and some people from marginalized minority groups — including Muslims and the Indigenous Adivasi — had good reasons not to trust public health workers handing out unsolicited medical advice.

Bhakti Dastane:

My reaction was not to get angry. I knew this resistance is going to come. So, I was prepared to convince patiently. And I said, “OK, not today. I will come tomorrow also.”

Céline Gounder:

And, over time, she had some success.

One family patriarch thought vaccination was a curse — and told his family this:

Bhakti Dastane:

He said, “Don’t listen to her, even if you think she’s saying the right thing.” So, for that person, I said, “OK, I’ll leave it like this.” And then, next day, just went there, not to talk about the smallpox or anything, just spend a day with them.

After three, four days, then he started listening to me. “OK. Now I think you are a good doctor, so, OK. What is it you want us to do?”

Céline Gounder:

What Bhakti wanted was to get his entire family vaccinated. And she did it.

[Music comes up under Bhakti]

Bhakti Dastane:

And once you put a trust in one family, then the neighborhood also get convinced and then your work becomes easy.

Céline Gounder:

Building trust makes the work go easier. That’s a pillar in public health.

But sometimes it can take months and even years to gain the trust of a community. And sometimes … there’s a tension between what’s expedient and what’s ethical.

Health workers are supposed to be patient, but epidemics are not patient.

Smallpox didn’t wait for trust and respect. It kept spreading. And lives were lost.

The smallpox warriors wanted to get to zero pox. And they wanted to get there fast.

Fueled by that urgency, their tactics were sometimes aggressive — and sometimes, crossed the line.

[Music fades out]

Céline Gounder:

Passion and frustration collided for Bhakti when she was working in Patna, the capital of Bihar.

People there would sometimes take off in the other direction as soon as they saw the vaccine volunteers.

So, to keep the locals from fleeing, Bhakti added two uniformed police officers to her team.

Bhakti Dastane:

Two people, which were at the end of the road, so they couldn’t run away.

Céline Gounder:

She resorted to intimidation, Bhakti says. But not violence.

Bhakti Dastane:

Hold down and that, that I didn’t do. But scare them with the police or any other thing: “You have to do this, and you have to take this.” Up to that. But not physical force. I, I never used physical force.

Céline Gounder:

But other health workers did.

Steve Jones:

My name is T. Stephen Jones, and — I go by Steve Jones — and, I had the good fortune to work on smallpox eradication in three countries.

Céline Gounder:

Steve was a true believer.

Steve Jones:

The idea that you could get rid of this plague that had caused deaths and disfiguration over centuries was just such an astounding idea that I wanted to be able to say that I had been part of it.

Céline Gounder:

When he arrived in Bihar in 1974, there was so much work to do.

[Music starts]

Céline Gounder:

Juggling more than a hundred different smallpox outbreaks at once. And for each case, he had to survey and vaccinate the 20 or 25 households surrounding the infected home.

Steve says he did a lot to persuade people. Like, he vaccinated himself repeatedly to show it was safe.

But there were times when the push for “zero pox” got the best of him.

Steve Jones:

I vaccinated a woman who was not willing to be vaccinated. I had a bifurcated needle and I held onto her arm, and I vaccinated her. And she resisted.

Then the people of the village responded, and it got angry. And I was hit on the head and knocked to the ground.

Céline Gounder:

He ended up needing stitches.

Steve Jones:

I regret this, and I realized that I did the wrong thing, even if I hadn’t been bonked on the head.

[Music fades out]

Steve Jones:

I was passionate and believed that it was a really important goal to achieve, and I made a mistake.

I learned about being overzealous and not treating people with respect.

Céline Gounder:

Bhakti Dastane says that she also came away with regrets about resorting to intimidation.

Bhakti Dastane:

Definitely using the force was not the proper thing to do, looking back now. But at that time, we were enthusiastic and trying to zero pox and so that a hundred percent vaccination.

[Music starts]

Céline Gounder:

During the campaign in India, there were instances of not just coerced vaccination, but of physical force.

Medical historian Sanjoy Bhattacharya is a professor of medical and global health histories at the University of Leeds in the United Kingdom.

He says the Adivasi Indigenous people of India were among the most frequently vaccinated under duress.

Sanjoy Bhattacharya:

They were encircled, by often Indian paramilitaries or police forces, and then groups of Indian and overseas workers would go into these villages.

Céline Gounder:

A lot like the treatment of Indigenous people in the U.S., the Adivasi have been traditionally marginalized and exploited. Many of them were understandably suspicious of government health and of course vulnerable to coercion.

Sanjoy Bhattacharya:

Often kick down doors, often pull people from places they were hiding in and forcibly vaccinate them, literally sit on them and vaccinate them.

[Music out]

Céline Gounder:

Today, around 50 years later, Sanjoy has spoken with villagers who still remember.

Sanjoy Bhattacharya:

They remember these pink, unfriendly — that is a terminology they use — pink, unfriendly people who would come in, shout at them, and not really engage them at all. I mean, what sort of leadership is that?

Céline Gounder:

Sanjoy rejects the idea that strong-arm tactics were somehow OK because of the urgency of the mission.

Sanjoy Bhattacharya:

Efficiency? By whose standard? None of us would like to be sat on by a 6-foot-tall and rather heavy man.

Céline Gounder:

And, he says, in the long run, force is usually counterproductive, creating a ripple of pushback, which ends up being more costly than leaving people unprotected.

[Music starts under Sanjoy]

Sanjoy Bhattacharya:

Any public health goal can be achieved without force. It needs engagement. It needs self-awareness; it needs humility. It needs money and time.

Céline Gounder:

Engagement takes time, and it’s built on trust.

When we come back, epidemiologist and researcher Sandhya Kajeepeta will join us to talk about just that.

Sandhya Kajeepeta:

I remember in early 2020 seeing news stories of very violent arrests of Black New Yorkers for alleged violations of covid mandates that were extremely vague.

Céline Gounder:

That’s after the break.

[Music out]

Céline Gounder:

By the end of April 2020, there had been over 18,000 covid deaths in New York City. I was working at a large public hospital in Manhattan — Bellevue.

Remember, at that time, there’s still a lot we didn’t know.

Our best advice was to tell everyone to stay home.

In cities like New York, police were tasked with enforcing these new rules around social distancing and masking.

But the results, they weren’t always good.

[Music begins]

Newscaster:

The 33-year-old seen getting thrown to the ground and slapped repeatedly in what started as social distancing enforcement along Avenue D and East Ninth Street.

Newscaster:

It is the most recent incident involving the NYPD [New York Police Department] social distancing enforcement that has come under fire.

[Music out]

Céline Gounder:

Seeing that footage of Black New Yorkers being arrested really upset me.

And I wondered, was this enforcement doing more harm than good?

I wanted to know. So, I talked about it with social epidemiologist Sandhya Kajeepeta.

She studied how police enforced these rules and how it impacted public health during the first months of the pandemic.

Sandhya Kajeepeta:

In my neighborhood in Harlem, I would see huge numbers of police officers issuing citations and making arrests in response to these mandates. But if I went downtown, to the southern part of Central Park, or to the West Village, I would see parks department employees handing out free masks.

Céline Gounder:

I definitely saw that too. Like, just walking to work at Bellevue Hospital, I’d see groups of people picnicking in Madison Square Park — unmasked.

But I never saw the NYPD breaking up those gatherings. That was in a predominantly white neighborhood in midtown Manhattan.

So, Sandhya, when you looked at summons and arrest data, how were the police enforcing those rules?

Sandhya Kajeepeta:

We found ultimately that neighborhoods in New York City with a higher percentage of Black residents also had a higher rate of pandemic policing.

Céline Gounder:

From your work we see that the enforcement of covid mitigation measures and mandates was unfair, but what about the public health results? Did these measures help curb infections?

Sandhya Kajeepeta:

There’s this really clear irony of trying to promote social distancing by instead increasing forced physical interactions between police and community members. And if people were held in jail because of a covid mandate violation, then they faced an even higher risk of covid infection, because the city’s jail was among the country’s top hot spots for coronavirus infections at this time.

It seems very clear that this approach was antithetical to public health broadly and to curbing the spread of the virus.

Céline Gounder:

Yeah, and on top of that, it made people more skeptical about the pandemic safety measures we were recommending.

Sandhya Kajeepeta:

Yeah, I think there’s certainly a growing body of evidence documenting how police and criminal legal systems more broadly can erode trust in public institutions.

Thinking about the covid pandemic, when I was seeing news coverage of police officers violently arresting and placing their knee on the neck of a Black man in New York, just for allegedly talking to someone too closely, or seeing footage of police forcing a Black woman to the ground in front of her child for allegedly wearing her mask improperly — that’s going to make me question whether public institutions really have our best interests in mind.

I think anyone can see that and recognize that violence and punishment is not getting us to the goal of safeguarding public health and is quite clearly putting people at risk.

Céline Gounder:

There will be more epidemics and pandemics in our lifetimes. What would you like to see done differently when we see the next infectious disease outbreak?

Sandhya Kajeepeta:

I think the mandates themselves are such a powerful and important message to send to people, that, you know, we’re all working together, we all have an individual responsibility to control the spread of the virus.

But I think when it was announced that police would be used to enforce these mandates, many people in New York City could very quickly predict what would happen, because we’ve seen this racialized pattern of policing be replicated time and time again.

[“Epidemic” theme music begins]

Trust in public institutions is such an important part of encouraging and motivating behavior change. But police enforcement can often have the opposite effect, of eroding that trust.

Céline Gounder:

Next time on “Epidemic” …

Tim Miner:

Occasionally you have to park your motorcycle, take your shoes and socks off, and walk across a leech-infested paddy field to get to the next case.

Céline Gounder:

“Eradicating Smallpox,” our latest season of “Epidemic,” is a co-production of KFF Health News and Just Human Productions.

Additional support provided by the Sloan Foundation.

This episode was produced by Jenny Gold, Zach Dyer, Taylor Cook, and me.

Our translator and local reporting partner in India was Swagata Yadavar.

Taunya English is our managing editor.

Oona Tempest is our graphics and photo editor.

The show was engineered by Justin Gerrish.

We had extra support from Viki Merrick.

Music in this episode is from the Blue Dot Sessions and Soundstripe. We’re powered and distributed by Simplecast.

This episode featured news clips from ABC7 New York and NBC 4 New York.

If you enjoyed the show, please tell a friend. And leave us a review on Apple Podcasts. It helps more people find the show.

Follow KFF Health News on Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok.

And find me on Twitter @celinegounder. On our socials there’s more about the ideas we’re exploring on the podcasts.

And subscribe to our newsletters at kffhealthnews.org so you’ll never miss what’s new and important in American health care, health policy, and public health news.

I’m Dr. Céline Gounder. Thanks for listening to “Epidemic.”

[”Epidemic” theme fades out]

Credits

Additional Newsroom Support

Lydia Zuraw, digital producer

Tarena Lofton, audience engagement producer

Hannah Norman, visual producer and visual reporter

Simone Popperl, broadcast editor

Chaseedaw Giles, social media manager

Mary Agnes Carey, partnerships editor

Damon Darlin, executive editor

Terry Byrne, copy chief

Chris Lee, senior communications officer

Additional Reporting Support

Swagata Yadavar, translator and local reporting partner in India

Redwan Ahmed, translator and local reporting partner in Bangladesh

Epidemic is a co-production of KFF Health News and Just Human Productions.

To hear other KFF Health News podcasts, click here. Subscribe to Epidemic on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google, Pocket Casts, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

This article was produced by KFF Health News, a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF — the independent source for health policy research, polling, and journalism.