The Affordable Care Act struck a popular chord by allowing adult children to obtain health coverage through a parent’s plan until their 26th birthday.

Now, seeking broad support for their efforts to repeal and replace the ACA, House Republicans have kept that guarantee intact. But it’s not clear whether that provision will be successful or a destabilizing force in the insurance marketplace.

The policy has proven to be a double-edged sword for the ACA’s online health exchanges because it has funneled young, healthy customers away from the overall marketplace “risk pool.” Insurers need those customers to balance out the large numbers of enrollees with chronic illnesses who drive up insurers’ costs — and ultimately contribute to higher marketplace premiums.

Joseph Antos, a health economist with the American Enterprise Institute, a Washington, D.C.-based conservative think tank, said the ability for young adults to stay on family plans represents a “critical mistake” within the health law, cutting off insurers from a large, healthy demographic that likely would be able to afford a health care plan.

“This is essentially an ideal group for an insurance company,” he said. “They’re not going to use many services, and they’re going to pay their bills.”

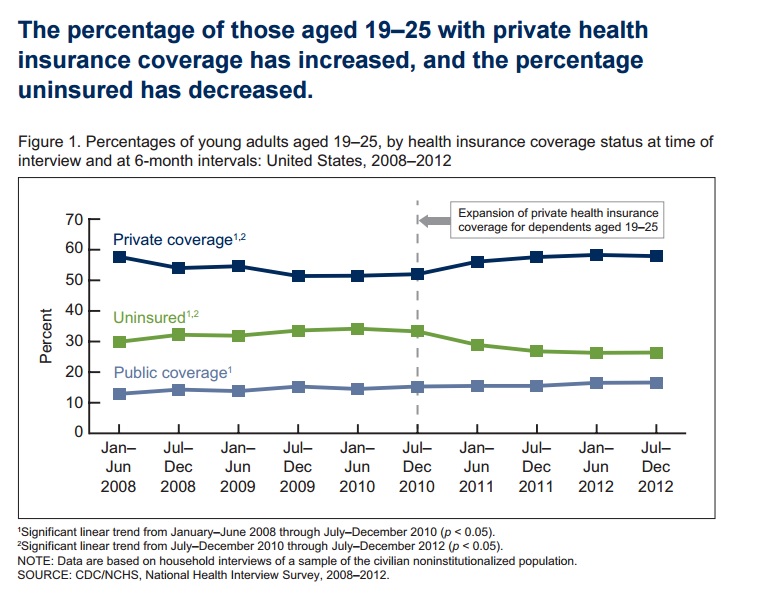

The young-adult provision went into effect in September 2010 and families put it to use quickly, with many young adults leaving their own insurance plans. A report published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2013 found the percentage of adults ages 19 to 25 with personal plans fell from nearly 41 percent in 2010 to just over 27 percent in 2012, while the ratio of those covered through a family member’s plan rose by 14 percentage points.

And the Department of Health and Human Services said last year that final 2016 marketplace enrollment numbers showed more than 6 million people ages 19 to 25 gained insurance through the health law, including 2.3 million who went onto their family health plan between September 2010 and when online marketplaces began operating in 2014.

Cara Kelly, a vice president of the health care consulting firm Avalere Health, said the provision’s effect must be understood in the context of the law’s implementation. Affordability and the selection of plans available in the marketplace also could have influenced the decision among young adults to buy or shirk insurance, Kelly said. Even if the provision had not been included in the law, she said, one can’t assume that the young adults would have signed up for coverage.

A little more than a quarter of marketplace customers in 2016 were adults ages 18 to 34, according to data from the Department of Health and Human Services. But federal officials and insurers had hoped for higher rates, noting that the group made up about 40 percent of the potential market.

Public support for the young-adult provision makes it difficult to take away. A survey conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation in December 2016 found that 8 in 10 Republicans and 9 in 10 Democrats favored the benefit. (Kaiser Health News is an editorially independent program of the foundation.)

The young-adult provision went into effect in September 2010 and families put it to use quickly, with many young adults leaving their own insurance plans. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

“It has been extremely popular,” said Al Redmer Jr., the Maryland insurance commissioner and chairman of the health insurance and managed care committee within the National Association of Insurance Commissioners. “So with that being the case, I don’t know if politically there’s an appetite to unwind it.”

Republicans have opted for different measures than the ACA to attract increased numbers of healthy, young customers and make the risk pools vibrant. To keep prices lower for these customers, the bill allows insurers to charge older people up to five times more than young adults. Under the ACA, that difference is 3-to-1, and Republicans say that made prices too expensive for younger customers.

It would also replace the health law’s individual mandate — the requirement that almost everyone have health insurance or face a penalty — with a 30 percent surcharge on their premium for late enrollment or allowing your insurance to lapse for more than 63 days within a year.

The overall effect, according to an analysis conducted by the Congressional Budget Office, would be a more stable market with a larger number of healthy enrollees. The report also estimated the bill could result in 24 million more people being uninsured.

But the bill also has disincentives for those young people. To help pay for premiums, low-income people will get tax credits based on age and household income. Older people would get $4,000 per year, twice as much as younger customers.

Insurers have reacted cautiously. The insurer Blue Cross Blue Shield Association released a statement this month expressing its support for increasing affordability for younger enrollees. But it also raised concerns about the Republicans’ tax credit proposal. A benefit based on age alone “does not give healthy people enough incentive to stay in the market, especially in the absence of an individual mandate.”

The insurance trade group America’s Health Insurance Plans sent a letter to House Republican committee chairmen voicing support for the 5-to-1 age-band rating and tax credits based on age.

“We have stated previously that there is no question that younger adults are under-represented in the individual market,” the letter said. “Recalibrating and reforming the way in which the premium assistance is structured will encourage younger Americans to get covered.”

KHN reporter Mary Agnes Carey contributed to this article.

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.