Dr. Katherine Pannel was initially thrilled to see President Donald Trump’s physician is a doctor of osteopathic medicine. A practicing D.O. herself, she loved seeing another glass ceiling broken for the type of doctor representing 11% of practicing physicians in the U.S. and now 1 in 4 medical students in the country.

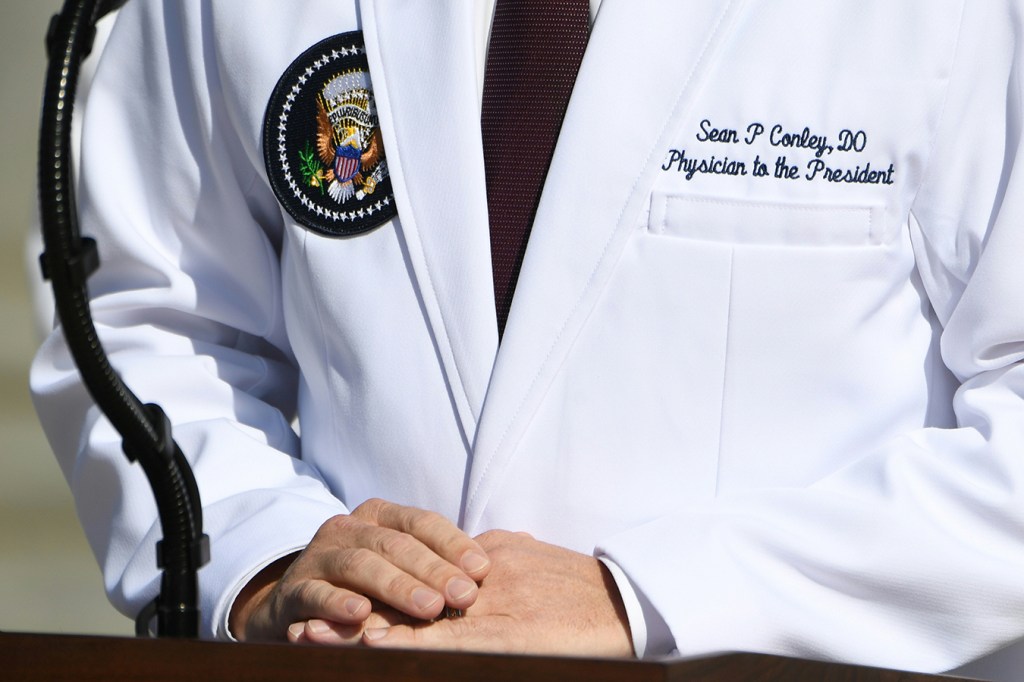

But then, as Dr. Sean Conley issued public updates on his treatment of Trump’s COVID-19, the questions and the insults about his qualifications rolled in.

“How many times will Trump’s doctor, who is actually not an MD, have to change his statements?” MSNBC’s Lawrence O’Donnell tweeted.

“It all came falling down when we had people questioning why the president was being seen by someone that wasn’t even a doctor,” Pannel said.

The osteopathic medical field has had high-profile doctors before, good and bad. Dr. Murray Goldstein was the first D.O. to serve as a director of an institute at the National Institutes of Health, and Dr. Ronald R. Blanck was the surgeon general of the U.S. Army. Former Vice President Joe Biden, challenging Trump for the presidency, also sees a doctor who is a D.O. But another now former D.O., Larry Nassar, who was the doctor for USA Gymnastics, was convicted of serial sexual assault.

Still, with this latest example, Dr. Kevin Klauer, CEO of the American Osteopathic Association, said he’s heard from many fellow osteopathic physicians outraged that Conley — and by extension, they, too — are not considered real doctors.

“You may or may not like that physician, but you don’t have the right to completely disqualify an entire profession,” Klauer said.

For years, doctors of osteopathic medicine have been growing in number alongside the better-known doctors of medicine, who are sometimes called allopathic doctors and use the M.D. after their names.

According to the American Osteopathic Association, the number of osteopathic doctors grew 63% in the past decade and nearly 300% over the past three decades. Still, many Americans don’t know much about osteopathic doctors, if they know the term at all.

“There are probably a lot of people who have D.O.s as their primary [care doctor] and never realized it,” said Brian Castrucci, president and CEO of the de Beaumont Foundation, a philanthropic group focused on community health.

So What Is the Difference?

Both types of physicians can prescribe medicine and treat patients in similar ways.

Although osteopathic doctors take a different licensing exam, the curriculum for their medical training — four years of osteopathic medical school — is converging with M.D. training as holistic and preventive medicine becomes more mainstream. And starting this year, both M.D.s and D.O.s were placed into one accreditation pool to compete for the same residency training slots.

But two major principles guiding osteopathic medical curriculum distinguish it from the more well-known medical school route: the 200-plus hours of training on the musculoskeletal system and the holistic look at medicine as a discipline that serves the mind, body and spirit.

The roots of the profession date to the 19th century and musculoskeletal manipulation. Pannel was quick to point out the common misconception that their manipulation of the musculoskeletal system makes them chiropractors. It’s much more involved than that, she said. Dr. Ryan Seals, who has a D.O. degree and serves as a senior associate dean at the University of North Texas Health Science Center in Fort Worth, said that osteopathic physicians have a deeper understanding than allopathic doctors of the range of motion and what a muscle and bone feel like through touch.

That said, many osteopathic doctors don’t use that part of their training at all: A 2003 Ohio study said approximately 75% of them did not or rarely practiced osteopathic manipulative treatments.

The osteopathic focus on preventive medicine also means such physicians were considering a patient’s whole life and how social factors affect health outcomes long before the pandemic began, Klauer said. This may explain why 57% of osteopathic doctors pursue primary care fields, as opposed to nearly a third of those with doctorates of medicine, according to the American Medical Association.

Pannel pointed out that she’s proud that 42% of actively practicing osteopathic doctors are women, as opposed to 36% of doctors overall. She chose the profession as she felt it better embraced the whole person, and emphasized the importance of care for the underserved, including rural areas. She and her husband, also a doctor of osteopathic medicine, treat rural Mississippi patients in general and child psychiatry.

Given osteopathic doctors’ likelihood of practicing in rural communities and of pursuing careers in primary care, Health Affairs reported in 2017, they are on track to play an increasingly important role in ensuring access to care nationwide, including for the most vulnerable populations.

Stigma Remains

To be sure, even though the physicians end up with similar training and compete for the same residencies, some residency programs have often preferred M.D.s, Seals said.

Traditional medical schools have held more esteem than schools of osteopathic medicine because of their longevity and name recognition. Most D.O. schools have been around for only decades and often are in Midwestern and rural areas.

While admission to the nation’s 37 osteopathic medical schools is competitive amid a surge of applicants, the grade-point average and Medical College Admission Test scores are slightly higher for the 155 U.S. allopathic medical schools: The average MCAT was 506.1 out of 528 for allopathic medical school applicants over a three-year period, compared with 503.8 for osteopathic applicants for 2018.

Seals said prospective medical students ask the most questions about which path is better, worrying they may be at a disadvantage if they choose the D.O. route.

“I’ve never felt that my career has been hindered in any way by the degree,” Seals said, noting that he had the opportunity to attend either type of medical school, and osteopathic medicine aligned better with the philosophy, beliefs and type of doctor he wanted to be.

Many medical doctors came to the defense of Conley and their osteopathic colleagues, including Dr. John Morrison, an M.D. practicing primary care outside of Seattle. He was disturbed by the elitism on display on social media, citing the skills of the many doctors of osteopathic medicine he’d worked with over the years.

“There are plenty of things you can criticize him for, but being a D.O. isn’t one of them,” Morrison said.

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.