At age 7, Josh Hardy became the poster child for a movement to help desperately ill or dying patients access experimental therapies which, they hope, will save their lives.

People around the world rallied 2½ years ago when a small biotech company refused to provide the Fredericksburg, Va., boy, who had battled cancer since infancy, with an experimental drug that doctors believed could save Josh from a life-threatening infection. Within days, a social media campaign called #SaveJosh, sparked by his mother’s anguished Facebook post and propelled by well-connected supporters, spurred thousands of people to contact the company, Chimerix Inc. of North Carolina, prompting it to release the drug.

For a time, Josh recovered. But his body remained weakened by disease, and Josh died last month at age 10.

Yet the #SaveJosh campaign has had an enduring impact on efforts to expand “compassionate use” of experimental therapies.

Josh’s story — and the plight of thousands of others facing life-threatening diseases with no government-approved therapies — has inspired multiple, sometimes conflicting efforts by government, industry and activists to make experimental medications more widely available.

The Food and Drug Administration, whose staff initiated the clinical trial that provided Josh his medication, has reduced the time that doctors spend requesting an unapproved drug to just 45 minutes. The agency says it approves 99 percent of such applications, granting most requests in four days and emergency requests within hours. The agency is even considering hiring “navigators” to walk doctors through the process.

Nonetheless, some patient advocates are leading a drive to provide access to experimental drugs without the FDA’s help.

Thirty-two states have passed laws designed to give patients the “right to try” an unapproved medication, by protecting doctors who provide such therapies from losing their state medical licenses. Republicans have included the right to try unapproved drugs in their national presidential platform.

Christina Sandefur, executive vice president at the libertarian Goldwater Institute, which has coordinated right-to-try efforts, said terminally ill patients shouldn’t have to ask for a “permission slip” from the FDA. “If you are dying and you’ve exhausted all other options and this medication has passed basic safety testing, you should be able to work directly with the drug companies and your doctor without having to go through the FDA.”

Yet even some supporters of the right to try acknowledge the state laws have helped relatively few patients.

Sen. Ron Johnson (R-Wis.) chairman of the Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee, introduced a federal right-to-try bill in May as a way to bolster the state initiatives. At a hearing in September, Johnson said his bill “simply says patients, who have no alternative and are facing death, should have the right to try to save their own lives — and the right to hope.”

Drug developers get the message

The renewed interest in compassionate use — which first emerged as a national issue during the AIDS crisis of the 1980s — also has spurred pharmaceutical companies to ramp up “expanded access” programs.

Some are concerned that social media campaigns give unfair advantages to families who are well-connected and media-savvy. Minorities, immigrants and people who aren’t fluent in English could be less able to mount effective campaigns, said Alison Bateman-House, a bioethicist at New York University Langone Medical Center. She’s been working with Johnson & Johnson to help ensure its compassionate use system allocates drugs fairly.

Marathon Pharmaceuticals, which is developing a steroid to treat a fatal disease called Duchenne muscular dystrophy, has been working with patient advocacy groups to enroll patients in its compassionate use program. The Illinois company anticipates enrolling 800 patients by February in its expanded access program for the steroid, called deflazacort.

While some drug developers were moved by Josh’s plight, others were motivated by a fear of negative publicity, Bateman-House said. Almost overnight, Chimerix became a symbol of corporate indifference. Critics posted the home address of Chimerix executives online, and some received death threats. The company replaced its CEO within a month of the controversy.

“The majority of the pharmaceutical industry suddenly got terrified that they were going to be the next Chimerix,” Bateman-House said.

And while drug companies tend to look like the bad guys when they deny drug access, Bateman-House said there are legitimate reasons for caution. Experimental medications haven’t been fully tested for safety and could make people with terminal illnesses die faster and in more pain.

“Companies worry about the risk,” said Richard Klein, director of the FDA’s patient liaison program. His story was “really public and really in the limelight. If he had not done well, what would have happened to that tiny little company? They would have been at a tremendous disadvantage.”

Patient advocates disagree on strategy

Advocates for people with life-threatening illnesses disagree about the best way to expand access to experimental therapies.

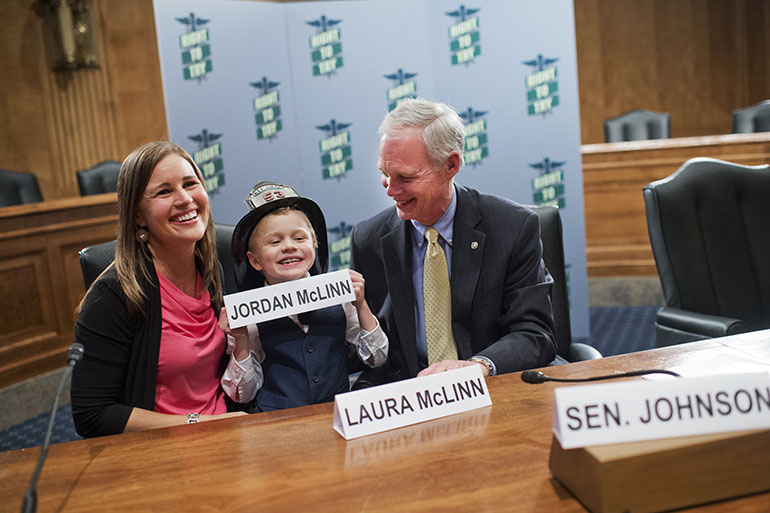

Laura McLinn, an Indianapolis mother whose 7-year-old suffers from Duchenne muscular dystrophy, supports right-to-try laws. She championed Indiana’s right-to-try legislation, and her son, Jordan, stood next to Gov. Mike Pence when he signed the bill into law.

Although Jordan looks perpetually cheerful, dressed for public photographs in a firefighter costume and helmet, he’s already beginning to decline. Jordan gets tired faster than he used to. He cries at night when his body hurts. He falls and can’t keep up with his friends. “He can’t do the things they are dong at recess and he doesn’t understand why,” McLinn told a Senate committee in February.

Laura McLinn, her son Jordan, 7, and Sen. Ron Johnson (R-Wis.) posed for photos after a news conference on “Right to Try” legislation last May. (Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call via Getty)

In spite of the McLinn family’s support for the right-to-try movement, Indiana’s law hasn’t helped Jordan access any experimental therapies.

Although Jordan is taking an unapproved steroid, McLinn hasn’t accessed it through right-to-try laws. She orders the medication through the mail from an overseas manufacturer. The FDA permits these orders under certain circumstances, such as when patients with serious disease have no alternatives.

McLinn said Jordan’s best hope for a medical breakthrough will come from a traditional clinical trial, overseen by the FDA and run by a Massachusetts pharmaceutical company, Sarepta Therapeutics, which won approval in September for another muscular dystrophy drug. McLinn said she hopes her son will begin the trial within months.

Some say right-to-try laws have accomplished little in the past two years.

“The right-to-try laws are something that a lot of families and patients are interested in, but they don’t really have any teeth in them,” said Dr. Valerie Cwik, executive vice president and chief medical and scientific officer at the Muscular Dystrophy Association.

Right-to-try laws wouldn’t have helped Josh Hardy, because the laws don’t require drug developers to actually make their medications available, Bateman-House said. The laws also don’t require that insurance companies pay for the treatments. The movement’s main intent is to undermine the FDA, Bateman-House said.

“The cruel reality with the right-to-try legislation is that it will not grant patients the immediate access to treatments they desperately need,” said Andrew McFadyen, executive director of the Isaac Foundation, a nonprofit based in Ontario, Canada, that funds research to fight MPS, the fatal genetic disease that afflicts his 12-year-old son.

The first doctor to openly acknowledge using a state right-to-try law, Houston cancer specialist Ebrahim Delpassand, came forward in September at Johnson’s hearing, where he testified via video. Delpassand said that he has given an unapproved drug, LU-177, to 78 patients with advanced neuroendocrine cancers under Texas’s right-to-try law.

Those numbers are dwarfed by the number granted expanded access by the FDA, which last year approved 1,262 requests for all drugs. The actual number of patients included in these FDA requests is much larger, because some requests were made on behalf of trials that include hundreds or even thousands of patients.

For example, about 35,000 patients received the lung cancer drug Iressa through expanded access before that drug was approved, said Klein.

At the Senate hearing, Johnson acknowledged that state right-to-try laws haven’t produced as many big wins as supporters had hoped.

Although state right-to-try laws protect doctors from losing their licenses if they prescribe unapproved drugs, physicians may be reluctant to use the laws, for fear of violating federal regulations, Johnson said.

Even in a right-to-try state, doctors such as Delpassand “are taking a huge risk” in providing unapproved treatments, Johnson said. “We need the federal law for the state laws to kick in. Until the federal government acts, the state laws are not effective.”

KHN’s coverage of end-of-life and serious illness issues, aging & improving care of older adults and prescription drug development, costs and pricing are supported by The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, The John A. Hartford Foundation and the Laura and John Arnold Foundation.