There’s an irony at the heart of the treatment of high blood pressure. The malady itself often has no symptoms, yet the medicines to treat it — and to prevent a stroke or heart attack later — can make people feel crummy.

“It’s not that you don’t want to take it, because you know it’s going to help you. But it’s the getting used to it,” said Sharon Fulson, a customer service representative from Nashville, Tenn., who is trying to monitor and control her hypertension.

The daily pills Fulson started taking last year make her feel groggy and nervous. Other people on the drugs report dizziness, nausea and diarrhea, and men, in particular, can have trouble with arousal.

“All of these side effects are worse than the high blood pressure,” Fulson said.

Research shows roughly half of patients don’t take their high blood pressure medicine as they should, even though heart disease is the leading cause of death in America. For many unfortunate people, their first symptom of high blood pressure is a catastrophic cardiac event. That’s why hypertension is called the “silent killer.”

A drug test is now available that can flag whether a patient is actually taking the prescribed medication. The screening, which requires a urine sample, is meant to spark a more truthful conversation between patient and doctor.

Fulson’s blood pressure has been a moving target, she said. She regularly checks it at home, but it sometimes registers as a little high. Even having it taken in a doctor’s office can add enough stress to elevate the results.

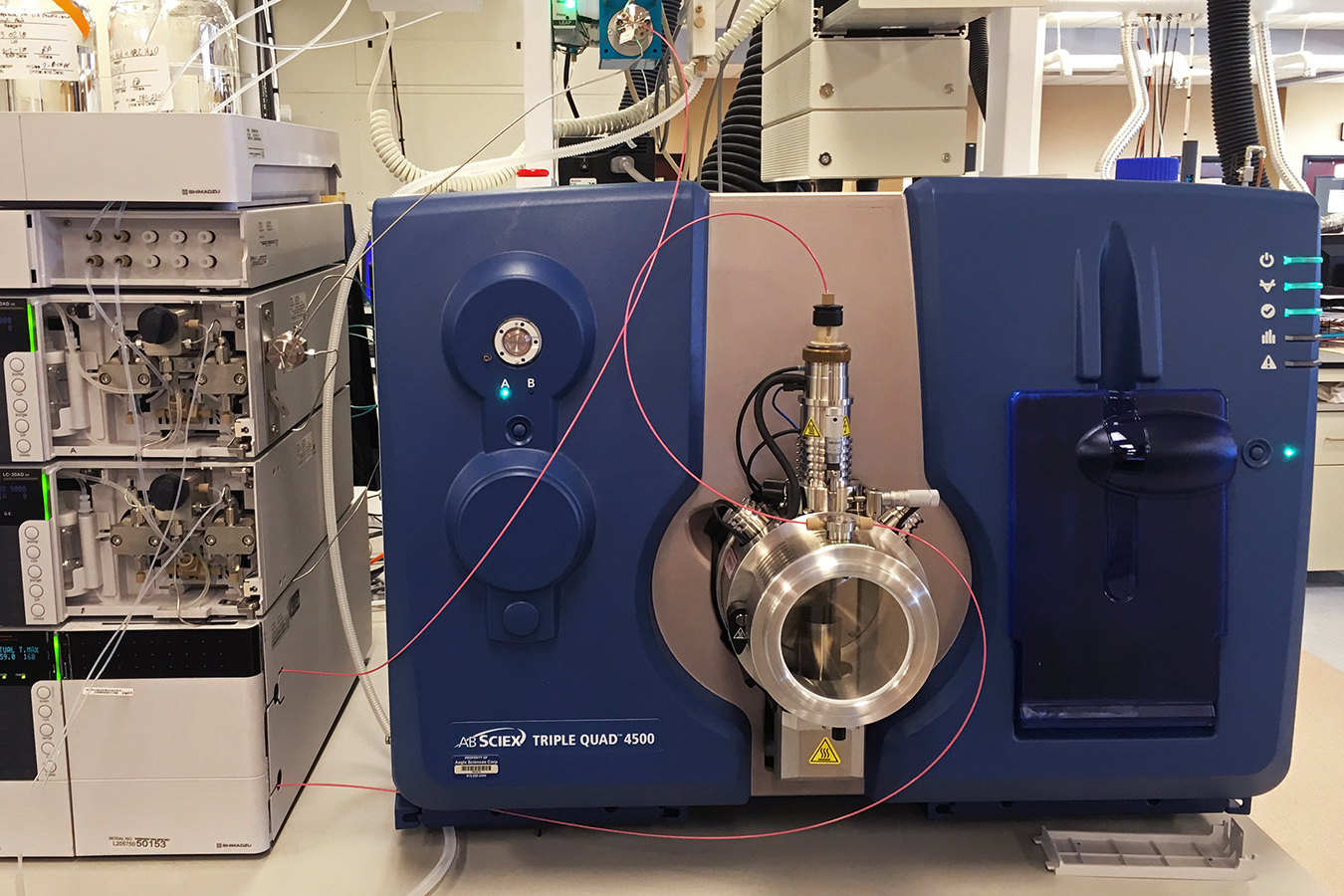

Research shows many patients skip the blood pressure medicine they’ve been prescribed, but don’t confess that to their doctors. Aegis Sciences now has equipment and a test that allows doctors to directly check via a patient’s urine sample. (Blake Farmer/WPLN)

This is why taking patients’ pressure — the familiar cuff test — doesn’t confirm for cardiologists whether patients are consistently taking their hypertension meds. The new drug test, dubbed KardiAssure, uses computers to analyze urine to search for 80 kinds of blood pressure and cholesterol medication, reporting the results in just three minutes.

The test can determine only whether a patient has taken pills in the past day or two. But Aegis Sciences Corp.’s CEO Frank Basile said that’s a starting point.

“What we give doctors is a tool that enables them to have a very focused conversation with their patients,” he said. Only after the problem is out in the open, he said, can doctors get to the reasons behind it.

The conversation starter has been effective for cardiologist Bryan Doherty in Dickson, Tenn., who has been working with Aegis to test the test. In one case, when the results showed a patient wasn’t regularly taking his medicine, though he’d claimed he was, he quickly confessed.

“He immediately turned around and told me that the cost was an issue,” Doherty said. “I think there was a degree of embarrassment there, potentially, or a feeling of letting me down in some way — something that had not come up in a 25-minute initial encounter when we had spoken before.”

Of course, the test has a cost, too — about $100 — though Doherty noted that insurance, including Medicare, has been covering it.

The conversation is important, Doherty said, because he can try less expensive prescriptions if cost is the issue, or experiment with different kinds of drugs if side effects are the problem. It’s worth the potentially uncomfortable encounter with the patient, he said, since the medication might make the difference between life and death.

The screening could also help a patient avoid other unnecessary tests or additional prescriptions, said Dr. Thomas Johnston. He runs the hypertension clinic at Centennial Medical Center in Nashville and is board president of the local chapter of the American Heart Association.

Other than calling the pharmacy to make sure people are refilling their prescription, he said, he generally takes their word for it.

“I think there are a lot of times where you’re questioning in your mind whether someone has taken their medicine or not,” he said. “I think it would be good for the patient, too, for the doctor to know that they’re not taking their medicine so that we may not go down the wrong pathway.”

Johnston, who is not affiliated with Aegis, said his only concern about using a drug test would be running the risk of setting up an adversarial relationship with a patient. But there’s a way around that, too, he said, by making them understand how vital it is to take the drug properly.

Sarah Avery of Nashville said she’s fully aware of the consequences.

“My daddy died because he didn’t take his medicine,” she said.

Hypertension runs in her family. Her mom and grandmother also battled high blood pressure. Still, the medication is such a drag, she said, that she’s decided at times to stop without consulting her doctor.

“I lied. Really, I lied,” she admitted. “He said, ‘Are you taking your medicine?’ I said, ‘Mmhmmm. Yeah, my momma makes sure that I do.’ I was just lying,” she said.

That is, until she, too, had a stroke. Now, she has three blood pressure medications and said she takes them without fail.

This story is part of a partnership that includes WLPN, NPR and Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.