In fall 2009, several dozen of the best minds in health information technology huddled at a hotel outside Washington, D.C., to discuss potential dangers of an Obama White House plan to spend billions of tax dollars computerizing medical records.

The health data geeks trusted that transitioning from paper to electronic records would cut down on medical errors, help identify new cures for disease and give patients an easy way to track their health care histories.

But after two days of discussions, the group warned that few safeguards existed to protect the public from possible consequences of rolling out the new technology so quickly. Because this software tracks the medicines people take and their vital signs, even a tiny error or omission, or a doctor’s inability to access the file quickly, can be a matter of life or death.

The experts at that September 2009 meeting, mainly members of the American Medical Informatics Association, or AMIA, agreed that safety should be a top priority as federal officials poured more than $30 billion into subsidies to wire up medical offices and hospitals nationwide.

The group envisioned creating a national databank to track reports of deaths, injuries and near misses linked to issues with the new technology.

It never happened.

Instead, plans for putting patient safety first — and for building a comprehensive injury reporting and reviewing system — have stalled for nearly a decade, because manufacturers of electronic health records (EHRs), health care providers, federal health care policy wonks, academics and Congress have either blocked the effort or fought over how to do it properly, an ongoing investigation by Fortune and Kaiser Health News shows.

Over the past 10 years, the parties have squabbled over how best to collect injury data, over who has the power to require it, over who should pay for it, and over whether to make public damning findings and the names of those responsible for safety problems.

In 2015, members of Congress derailed a long-planned EHR safety center, first by challenging the government’s authority to create it and later by declining to fund it. A year later, Congress stripped the Food and Drug Administration of its power to regulate the industry or even to track malfunctions and injuries.

“A lot of people involved with patient safety and medical informatics were horrified,” said Ross Koppel, a University of Pennsylvania sociologist and prominent EHR safety expert. Koppel said the industry won legal status as a “regulatory free zone” when it came to safety, an outcome he called a “scandal beyond belief.”

The Electronic Health Record Association, a trade group that represents more than 30 vendors, declined to comment on the safety issue.

Meanwhile, patients remain at risk of harm. In March, Fortune and KHN revealed that thousands of injuries, deaths or near misses tied to software glitches, user errors, interoperability problems and other flaws have piled up in various government-sponsored and private repositories. One study uncovered more than 9,000 patient safety reports tied to EHR problems at three pediatric hospitals over a five-year period.

Allegations of EHR-related injuries or other flaws have surfaced in the courts. KHN/Fortune examined more than two dozen such cases, such as a California woman who mistakenly had most of her left leg amputated because the EHR sent another patient’s pathology report indicating cancer to her medical file. A Vermont patient died after a doctor’s order to scan her brain for an aneurysm never made it from the computer to the lab.

Despite such incidents, experts believe EHRs have made medicine safer by eliminating errors due to illegible handwriting and in some cases speeding up access to vital patient files. But they also acknowledge they have no idea how much safer, or how much the systems could still be improved because no one — a decade after the federal government all but mandated their adoption — is assessing the technology’s overall safety record.

KHN and Fortune found that at least a dozen expert commissions, federal health IT panels and medical associations have echoed AMIA’s early call to track EHR safety risks only to be thwarted by objections from the industry or its allies, or by simple bureaucratic inertia. Some critics see the situation as a dispiriting Washington tale of corporate “capture” of government, while others wonder why a warning system to alert health officials to dangers with certain software is even controversial.

“How is it in the public interest for medical records software to have flaws that lead to deaths?” said Joshua Sharfstein, who served as FDA deputy commissioner when the safety issue flared up during President Barack Obama’s first term. These incidents “should be fully understood and investigated” and “not be able to be buried.”

Support for computerizing medical records has spanned the political spectrum. The health IT industry’s aversion to FDA oversight has won support at critical times both with liberals who embraced EHRs as a high-tech magic bullet for reforming the nation’s costly health care system and with free-market conservatives skeptical of red tape and government interventions.

The vendors protested they were overburdened with technical requirements that their software had to meet to qualify for the government subsidy program. Those specifications included many relatively small-bore features, like including a check box indicating the doctor had asked about the patient’s smoking status — and other tasks likely to have little impact on safety.

Complicating things further, many safety advocates themselves have worried that heavy-handed oversight — such as requiring approval of every software update — could actually make the technology less safe, stalling urgent software updates (not to mention stifling innovation and slowing the marketing of vital new technology).

After a contentious process in which consumer advocacy group Public Citizen accused FDA officials of collaborating with the devices industry to weaken oversight, Congress passed the 21st Century Cures Act. A few sentences buried in the law, signed by Obama in late 2016, all but shut the door on FDA regulation of EHRs.

The bipartisan law, which speeds up approvals for some medical therapies, states flatly that electronic health records are not medical devices subject to FDA scrutiny. Some longtime EHR safety advocates say they have all but given up hope for consensus on any system that would investigate and share findings from adverse events, as happens in other industries, like transportation and aviation.

“We have nothing like that,” said Justin Starren, director of the Center for Data Science and Informatics at Northwestern University. “We have the opposite … with vendors saying that customers are explicitly forbidden from publicizing problems they encounter.”

Starren noted that health care providers don’t like to share safety failures either: “It’s the liability fear. If an institution holds up its hand and says, ‘Our EHR might be killing people,’ the lawyers will be lining up outside the courthouse door.”

Less Red Tape Unleashes Red Flags?

In the months before the 2009 AMIA meeting, concern was mounting at the FDA over the rapidly advancing EHR rollout.

Since the mid-1980s, however, the FDA had considered health IT to present a low risk of harm because a “learned intermediary,” such as a doctor, was in charge. Most manufacturers agreed and insisted their products were not medical devices, but vehicles for processing and storing medical information.

The legal distinction is critical. While the FDA requires device makers to report adverse events, the policy in place gave EHR manufacturers a pass. At least one major vendor, Cerner Corp., has concluded that EHRs are, in fact, medical devices and has submitted some error reports to FDA’s public MAUDE database. But most manufacturers disagree and have not reported data, leaving a sizable gap in the agency’s grasp of possible hazards.

Within the FDA, some staffers urged the agency to rethink the hands-off stance given the rush by hundreds of health IT companies — many of them new entrants — to sell medical records software that tens of thousands of doctors, hospitals and patients would rely on.

On Sept. 22, 2009, FDA staff shared their views with deputy commissioner Sharfstein and his boss, commissioner Margaret Hamburg, at a “regulatory strategy” meeting. After hearing the pitch, Hamburg agreed the FDA “needs to be involved in the White House [EHR] initiative,” according to an agency memo. Hamburg had no comment for this article.

One former FDA official recalls tension mounting as the agency became more assertive, saying: “It was a big train going down the tracks at 80 miles per hour, and there were concerns that FDA would slow it down.”

The FDA sounded a public warning at a February 2010 hearing. The agency’s chief devices regulator, Jeffrey Shuren, testified that even with limited surveillance, the FDA had tied six deaths and 44 reported injuries to health information technology failures.

In all, Shuren said, the FDA had logged 260 reports of “malfunctions with the potential for patient harm” over the previous two years. In one case, the software filed results from emergency lab tests to the wrong patient’s electronic record.

Shuren described the reports as likely the “tip of the iceberg” and said they suggested “significant clinical implications and public safety issues.” He laid out three options for FDA involvement, the least burdensome being registration of EHR software and mandatory reporting of dangerous incidents. Through an agency spokesperson, Shuren declined to be interviewed for this article.

Shuren’s 2010 testimony did not appear to carry much weight with David Blumenthal, a Harvard physician chosen as the Obama administration’s point man for the digital medical record rollout. Blumenthal declined to comment.

Many in Blumenthal’s division, known as the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, or ONC, sympathized with the industry’s assertion that FDA regulation would discourage innovation, which, in turn, could cripple the president’s plans to revolutionize health care and save money. Blumenthal, who was convinced EHRs would make medicine much safer, described the FDA injury reports as “anecdotal.”

An obscure outpost of the Department of Health and Human Services in the second Bush administration, ONC under Blumenthal revved up as federal officials laid plans for distributing billions of stimulus dollars.

The stimulus law directed ONC to set up two diverse advisory panels so that no single faction of the health care sector could unduly influence policy. Yet it seemed clear, at least to skeptics, that ONC depended heavily on the goodwill, expertise and guidance of the technology community.

(Credit: Fortune)

Steven Findlay, who served on one of the panels as a representative of Consumers Union, said industry witnesses often “commandeered” the discussions because they “had the technical knowledge to steer things in a direction that they wanted.”

Safety “was not necessarily their first priority. They were building products to serve an industry and designing them to make money,” Findlay said in a recent interview.

Dean Sittig, a medical informaticist at UTHealth in Houston and early researcher on EHR safety, said ONC was “trying to promote” digital records “and there wasn’t a lot of interest in talking about things that could go wrong.” That conflict persists, he said. “They gave out $36 billion. It’s hard for them to say EHRs aren’t safe.”

The ONC did form a safety “working group.” The panel suggested that doctors and hospitals be required to report “potential hazards” and “incidents” to a national database or risk forfeiting government subsidies for purchasing records software, according to minutes from its March 12, 2010, meeting.

That idea never got past the drafting stage, however.

Glitches In The Matrix

In a nod to safety, ONC asked the National Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Medicine to weigh in, a move some at the FDA hoped would at the least lend support for nationwide collection of injury data.

When the 18-member expert panel held a public hearing in mid-December 2010, Shuren reappeared with updated FDA figures — about 370 reports of “adverse events or near misses” involving health IT since January 2008. Once again, he called FDA’s count a “small percentage of the actual [adverse] events that do occur.”

Among the causes he cited: failure of the software to interface properly with other technologies, user errors, design flaws and inadequate pre-market testing.

Shuren suggested EHRs were medical devices over which the FDA “has exercised enforcement discretion; meaning it has not enforced existing requirements,” an apparent reference to the hands-off policy. He called for “real-time collection, aggregation and analysis” of reports on the functioning of EHRs.

The Institute of Medicine panel in November 2011 called on HHS to make adverse incident reporting mandatory for vendors and voluntary for users. It also said HHS should ask Congress to approve a government-run injury monitoring system as rigorous as that used to promote airline safety that would both investigate and make its findings public. The FDA might not be the best-equipped agency to take on the task, the group noted.

The panel asserted that EHR vendors face “competing priorities, including maximizing profits and maintaining a competitive edge, which can limit shared learning and have adverse consequences for patient safety.”

One member called for even stricter oversight. In an impassioned dissent, Richard Cook, a Chicago radiologist and safety expert, argued EHRs were medical devices that necessitated the scrutiny of the FDA.

“At least a few U.S. citizens — perhaps more than a few — have died or have been maimed because of health IT. The extent of the injuries generated by health IT is unknown because no one has bothered to look for them in a systematic fashion,” Cook wrote in his dissent.

(Credit: Fortune)

Backtracking On Oversight

In 2012, Congress required FDA, ONC and the Federal Communications Commission to propose “risk-based” oversight for health IT that “promotes innovation, protects patient safety, and avoids regulatory duplication.”

Two years went by before the agencies did so. In April 2014, they promoted a “limited, narrowly tailored approach” to oversight led by the ONC as well as a “surveillance mechanism” to track adverse events and near misses.

ONC’s budget for the 2015 and 2016 fiscal years proposed spending $5 million for such a center, which ONC said would begin “a robust collection and analysis of health IT-related adverse events.”

But four House Republicans in June 2014 questioned whether ONC had the legal authority to set up the center.

Energy and Commerce Committee Chairman Fred Upton of Michigan, Vice Chairman Marsha Blackburn of Tennessee, health subcommittee Chairman Joseph Pitts of Pennsylvania and communications and technology subcommittee Chairman Greg Walden of Oregon argued that ONC had failed to satisfy their concerns over what Blackburn termed regulatory “mission creep.” At a House hearing in July 2014, Blackburn repeated her worry about “a misguided system of regulation.”

Former ONC director Karen DeSalvo said she was five months on the job and felt completely blindsided by the line of questioning — despite the National Academy of Sciences report years earlier that had advised HHS to seek approval from Congress to expand ONC’s oversight role. The center’s prospects dimmed further when the Congressional Research Service issued a report on the matter in early 2015 that seemed to side with the Republicans.

DeSalvo’s team later requested legislative authority to create the center, but the effort was not successful. ONC was granted legislative authority for other requests, however, empowering it to define interoperability and to crack down on vendors who improperly restrict access to medical records.

These days, many of the key players have conflicting opinions and recollections about what went wrong and why.

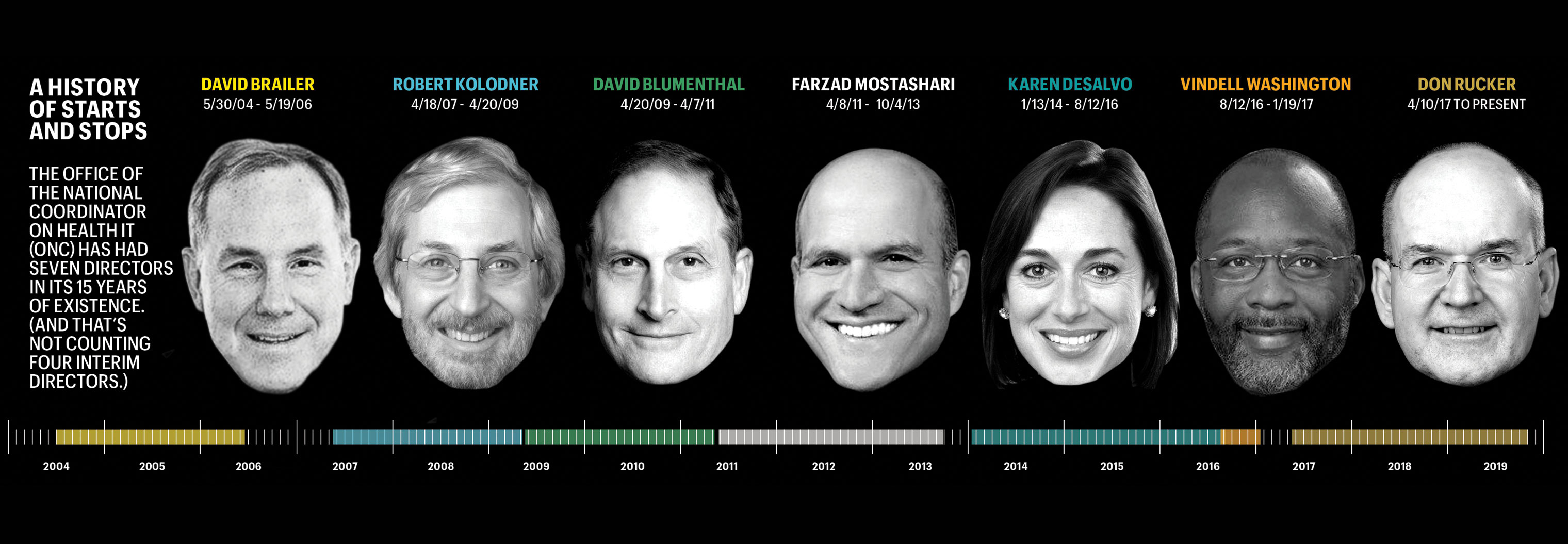

DeSalvo, now a professor of medicine and population health at Dell Medical School, said she really doesn’t know if something sinister torpedoed the safety center or it was just a matter of not enough people caring. “It was really just kind of start and stop,” she said. That’s perhaps not surprising, considering ONC has had seven directors in its 15 years of existence — and six since 2009, when the government made EHRs a national priority. (And that’s not counting four interim directors who collectively helmed the outfit for 16 months.)

Doug Fridsma, who left his role as ONC’s chief scientist in 2014, cited other factors that slowed the center’s momentum. He said uncertainty over its mission didn’t help gain the trust of the industry, while citing other thorny issues, such as who would foot the bill and whether its data might be used to discipline or otherwise harm vendors. Fridsma, now AMIA’s chief executive, said that government-sponsored regional patient safety organizations aren’t well equipped to conduct national oversight of EHR functions.

“It has resulted in a vacuum around health IT safety,” said Fridsma. “Congress has failed to make it a priority.”

Shifting Public Attention

Revisiting plans for a full-fledged EHR safety center holds little appeal to Don Rucker, the Trump administration’s ONC chief.

Rucker said he sees little value in collecting data on incidents often “years and years” after they occurred. Rapidly evolving technologies are making computer errors easier to recognize and remedy. “We can catch these things a lot earlier,” he said.

Rucker argues that the 21st Century Cures Act prohibits the industry from enforcing “gag” clauses that in the past have handcuffed hospitals and doctors from criticizing their EHRs. The Cures law includes fines of up to $1 million for “information blocking,” including taking steps to discourage EHR users from reporting adverse events and other problems for review.

New freedom to sound off assures that doctors and hospitals will begin sharing EHR problems, mitigating any need for mandatory reporting, in Rucker’s view. Rucker said he hopes to have the regulations in place by the end of the year.

The proposed ONC regulations cite a “strong public interest” in “open communication of information regarding health hazards, adverse events and unsafe conditions.” But that information won’t be shared with the public. ONC says all reports of problems are exempt from public release under the Freedom of Information Act. Congress gave these records the same legal status as income tax returns as part of the Cures law.

Jacob Reider, a former ONC interim director, said the government’s failure to do more to promote public awareness of safety concerns is disappointing — and even irresponsible — given its zeal in bringing EHRs into the mainstream of medicine.

“I remember internal conversations where we talked about ‘What is the equivalent of a plane crash that is going to get the attention of people?’” said Reider, who now practices family medicine in upstate New York. “‘Is it going to be a congressperson’s relative is harmed by health IT that causes the attention to shift?’ I would offer that still hasn’t happened yet, but someday it will. And gosh, wouldn’t it be a horrible thing that we have to wait for that to happen?”