More than two years after California’s surprise-billing law took effect, there’s one thing on which consumer advocates, doctors and insurers all agree: The law has been effective at protecting many people from bills they might have been saddled with from doctors who aren’t in their insurance network.

But the consensus stops there.

“In general, the law is working as intended,” said Anthony Wright, executive director of Health Access California, a patient advocacy group that pushed for the measure, AB-72. “Patients are protected and the providers are getting paid.”

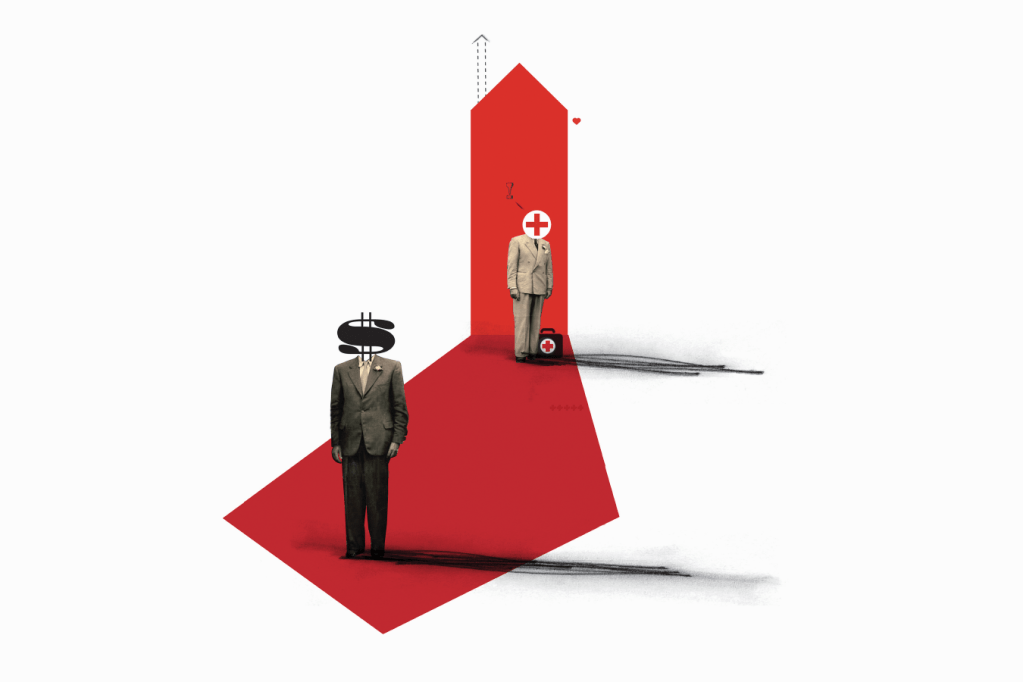

Physicians beg to differ. They say the law’s constraints on what insurers now pay has given the companies an unfair advantage in negotiations with doctors, which is leading to major changes in the industry that may affect patients.

Recent analyses by some researchers, however, cast doubt on some of the doctors’ dire warnings.

“The problem is that AB-72 is creating imbalances in the health care marketplace that are decreasing access to care,” said Dr. Antonio Hernandez Conte, an anesthesiologist whose specialty is among those most affected by the law.

The California law, which took effect in July 2017, protects consumers who use an in-network hospital or other facility from being hit with surprise bills when cared for by a doctor who has not contracted with their insurer. If that happens, consumers are responsible only for the copayment or other cost sharing that they would have owed if they had been seen by an in-network doctor.

Federal lawmakers are eyeing the California law as a possible model as they debate legislative proposals that would address surprise billing at the national level.

The California law applies to nonemergency services, since most state consumers were already protected for emergency care through an earlier court ruling.

It’s not unusual for patients who visit a hospital or ambulatory surgical center that is covered by their insurance to encounter specialists who aren’t, even in nonemergency situations.

For example, someone who has knee replacement surgery with an in-network surgeon at an in-network hospital may not realize that the anesthesiologist and assistant surgeon also scrubbing in on the operation are not.

Or a couple may be surprised to learn that the neonatologist caring for their baby in intensive care is outside their insurance network, even though the hospital where they gave birth is inside it. Diagnostic specialists like radiologists and pathologists whom patients rarely see may be out-of-network at an in-network hospital as well.

Under the California law, the doctor’s payment from an insurer in those situations is based on either the average contracted rate for similar services in the area or 125% of what Medicare would have paid, whichever is greater.

In a California Medical Association online survey released last month ― in which 855 physician practices responded ― nearly 90% of the doctors said that the law allowed insurers to shrink physician networks, thus limiting patients’ access to in-network doctors. Physicians blame the new law’s reimbursement rates for surprise out-of-network care. The payment standard made insurers less inclined to negotiate payments and reduced doctors’ bargaining power, the physicians say.

Those surveyed said they faced insurer payment rate cuts, refusal to renew their contracts and contract termination, among other problems.

This has led some physicians to try to gain leverage by consolidating practices, a move that can drive up health care costs significantly, the doctors warn.

The medical association did not respond to calls for comment on the survey.

Hernandez Conte, who chairs the legislative and practice affairs division of the California Society of Anesthesiologists, also pointed to data from the California Department of Managed Health Care showing that consumer complaints about access to care have risen from 415 in 2016 to 614 in 2018, a 48% jump.

Those complaints represent a minuscule number of consumers in the context of the more than 30 million Californians covered by commercial insurance or Medi-Cal, said Loren Adler, associate director at the University of Southern California-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Health Policy. Adler noted that there’s no way to know if the complaints had anything to do with the surprise-billing law.

Hernandez Conte also pointed to a study published in August by the research firm Rand Corp. that he said showed the law is eroding doctors’ leverage with insurers.

But that study ― a series of 28 interviews with doctors and others about their experiences in the first year after the law took effect ― wasn’t definitive, said author Erin Duffy, an adjunct policy researcher at Rand and postdoctoral fellow at the Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics at USC.

“It’s more a reflection of what are some of the potential things we should look at down the road,” she said.

Aside from individual examples of contracting problems cited by the physician group, researchers cite little evidence that patients are losing access to doctors who accept their insurance because of dwindling insurance networks.

The opposite appears to be true. USC-Brookings researchers published an analysis in September examining more than 17 million specialty claims by California physicians affected by the law. They found the share of services that specialty physicians delivered out-of-network at hospitals and ambulatory surgical centers declined by 17% after the law took effect.

When the law went into effect, there was a “precipitous” movement by affected physicians into insurance networks, said Adler, a co-author of the study.

Similarly, when the trade group America’s Health Insurance Plans surveyed 11 large California health insurers about in-network providers during the two years after the law took effect, it found that the numbers grew or remained flat across specialties. There was a 16% increase in the number of in-network physicians overall, including a 26% rise in diagnostic radiologists and an 18% bump in anesthesiologists.

The plight of consumers who go to an in-network facility and, unbeknownst to them, receive treatment from out-of-network doctors has garnered plenty of attention in recent months.

In a typical scenario, the doctor charges the insurance company for services, then turns around and bills the patient for whatever amount the insurance company doesn’t pay, a practice called balance billing. With no contract between the insurer and the doctor to set payment rates, the amounts billed by physicians are often higher than market rates, and the balance bills that patients face are many times higher than the regular copayment they would owe for in-network care.

Federal lawmakers are debating a number of measures that would address the issues at the federal level. The leading House and Senate bills would set minimum payment standards based on insurers’ median in-network rate for a service for applicable out-of-network care, similar to the California law.

A federal law is key to broadening the surprise-billing protections provided by California’s law, Wright said.

More than half of states now provide some level of consumer protection against surprise bills, and the efforts vary. But state surprise-billing laws protect only people insured by state-regulated plans. In California, that means 5.5 million consumers whose employers self-fund workers’ health claims directly, rather than through an insurance plan, aren’t covered by the law.

Since AB-72 was implemented, the Department of Managed Health Care hasn’t taken any enforcement actions against physicians for balance-billing patients in nonemergency situations, according to agency spokeswoman Rachel Arrezola. It has pursued a handful of cases against doctors for out-of-network balance billing in emergency situations, however.

As doctors and patient advocates wrangle over AB-72, lawmakers are pressing new protections for consumers. A state law recently barred balance billing by air ambulance services.

Starting in January, California consumers who are airlifted by an out-of-network air ambulance won’t be responsible for any more than their regular cost sharing for in-network providers.