For Alzheimer’s patients and their caregivers, social and emotional isolation is a threat. But hundreds of “Memory Cafes” around the country offer them a chance to be with others who understand, and to receive social and cognitive stimulation in the process.(Heidi de Marco/California Healthline)

LOS ANGELES — Doug and Connie Moore met at seminary. He was a student and pastor of an inner-city congregation, and she was a student and a public health nurse.

“She’s the one who drew me to the needs of the poor,” Doug says.

The pair wed in 1974, and Doug became a pastor at the First Evangelical Free Church of Los Angeles in 1983. They became deeply involved in their community and dedicated much of their free time to teaching English as a second language, creating tutoring programs and mentoring students in poor communities here and abroad.

But these days, the retired couple spends most of their time inside their modest two-bedroom apartment in Los Angeles. “There are a lot of hours spent alone,” says Doug, 69. “I can’t have a conversation with Connie.”

Connie, now 73, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, the most common form of dementia, in 2015. About 10% of Americans age 65 or older have the disease, according to the Alzheimer’s Association, including an estimated 670,000 people in California.

Doug, Connie’s primary caregiver, knows his wife needs as much stimulation as possible. So, twice a month, the Moores visit a program often referred to as a “Memory Cafe,” which offers social activities for people living with Alzheimer’s and dementia — and their caregivers. Activities include art, music, poetry, presentations and social interaction.

There are more than 800 regular gatherings around the country listed in the Memory Cafe directory, including more than 20 in California. Some meetings go by different names such as “Memory Mornings” and aren’t listed in the directory. The gatherings take place in coffee shops, hospitals, libraries, schools, senior centers and faith-based organizations. Free of charge to participants, the cafes are usually funded by grants, individuals, corporate sponsorships or faith-based organizations.

“Participating in social activities does not just provide social and cognitive stimulation for both the caregiver and the loved one, but they give each the opportunity to create new social groups for themselves with people who understand their situation,” said Susan Howland, programs director for the Alzheimer’s Association California Southland Chapter.

Doug and Connie Moore have been married for 45 years and have two children and one grandchild. Doug says he never dreamed his wife would get Alzheimer’s. After hearing the diagnosis, he says, “we both wept.”(Heidi de Marco/California Healthline)

Every morning, Doug reads Connie Scriptures from the Bible while she eats breakfast. Doug says his faith has remained solid through the process of caring for his wife. “Not to say that there are not moments when I come to tears,” he says. “But I can see her faith is still there.”(Heidi de Marco/California Healthline)

Before she retired, Connie was the director of nursing services for the Los Angeles Unified School District, in charge of seven-figure budgets and a large staff. When her ability to do math started to fail, Doug knew something was wrong. Connie needs help bathing and dressing, but still remembers Doug, her children and the names of her two Siamese cats — Frodo and Emi.(Heidi de Marco/California Healthline)

Connie’s Alzheimer’s was diagnosed early but advanced rapidly. As the disease progressed, the couple faced inevitable sadness and occasional questions of “Why me, Lord?” Doug says. “She always verbalized she feared she would be abandoned because of the disease.”(Heidi de Marco/California Healthline)

Doug helps Connie get dressed for their Memory Mornings meeting. Picking out his wife’s clothes has been a challenge because, Doug says, he’s not entirely sure how to put together an outfit. A parishioner from his church helps a few hours a week, choosing outfits for the coming days.(Heidi de Marco/California Healthline)

As Connie’s dementia progresses, dressing and grooming become harder for her. For now, she is still able to comb her hair and brush her teeth.(Heidi de Marco/California Healthline)

Doug and Connie head to the local Alzheimer’s Los Angeles office, about five minutes from their apartment, for their bimonthly Memory Mornings gathering. The activities include pet therapy, arts, music, dance and storytelling.(Heidi de Marco/California Healthline)

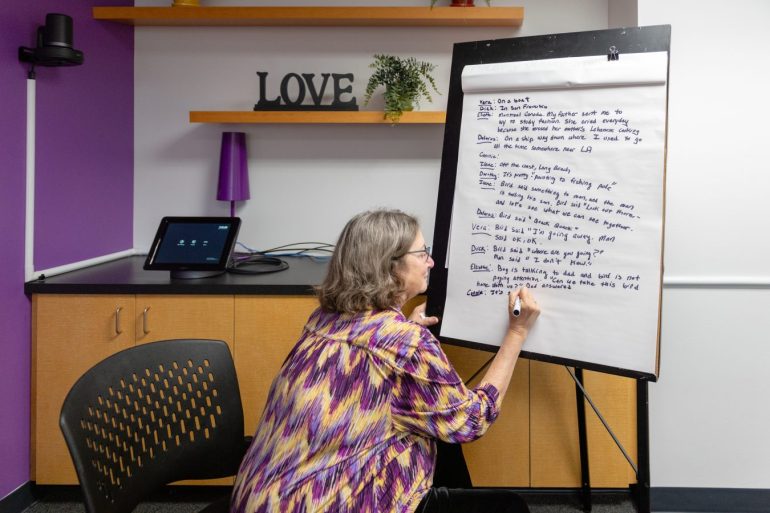

Licensed clinical social worker Sarah Jacobus leads a group of 19 caregivers and patients in an exercise called TimeSlips, which is an improvisational storytelling technique that stimulates the imagination of people with Alzheimer’s. “People may not remember that I’ve been there a week ago, but they remember the pictures and the storytelling,” she says.(Heidi de Marco/California Healthline)

As part of the TimeSlips exercise, all participants are given the same photograph and asked to answer questions about what’s happening in the scene. "Every person in the group responded in their own way, with a range of verbal capacity and lucidity. But they responded!" Jacobus says.(Heidi de Marco/California Healthline)

Linda Goldfinger, the facilitator of Memory Mornings, writes down the group’s descriptions of what is happening in the photograph. At the end of the exercise, she compiles the responses into a story, types it up and gives a copy to each participant.(Heidi de Marco/California Healthline)

Karen Pearson and her partner, Ilene Barg, work on formulating a description of the photograph. Karen is Ilene’s caregiver and a regular participant in the program. “The connections being made are so valuable,” Pearson says. “No matter what the content, we always walk away with a good feeling.”(Heidi de Marco/California Healthline)

The meetings allow Connie to interact with others with the same disease, Doug says, and they help him learn new ways to engage and entertain Connie at home. But the gatherings also serve as a reality check on Connie’s cognitive abilities. “Today, she could not verbalize or answer the questions,” Doug says. “In my mind, I would put her at the bottom of the group.”(Heidi de Marco/California Healthline)

Doug and Connie head home after spending two hours at the Memory Mornings meeting. The meetings are not meant to serve as respite for the caregiver, but as a safe place where the couple can socialize with others in the same situation.(Heidi de Marco/California Healthline)

Doug prepares lunch for Connie after returning from the meeting. Connie says she’s hungry, but she doesn’t say much else. "I try to talk to her," Doug says. "But you can’t have a dialogue with her."(Heidi de Marco/California Healthline)

Connie keeps herself busy for hours fiddling with random objects, such as Frodo’s felt cat toy. Even though Doug tries to keep a busy calendar for himself and Connie, he still feels a sense of loneliness. “There are a lot of hours spent alone, no matter what we do,” he says.(Heidi de Marco/California Healthline)