Two invasive species of mosquitoes that can carry Zika, dengue, yellow fever and other dangerous viruses are spreading in California — and have been found as far north as Sacramento and Placer counties.

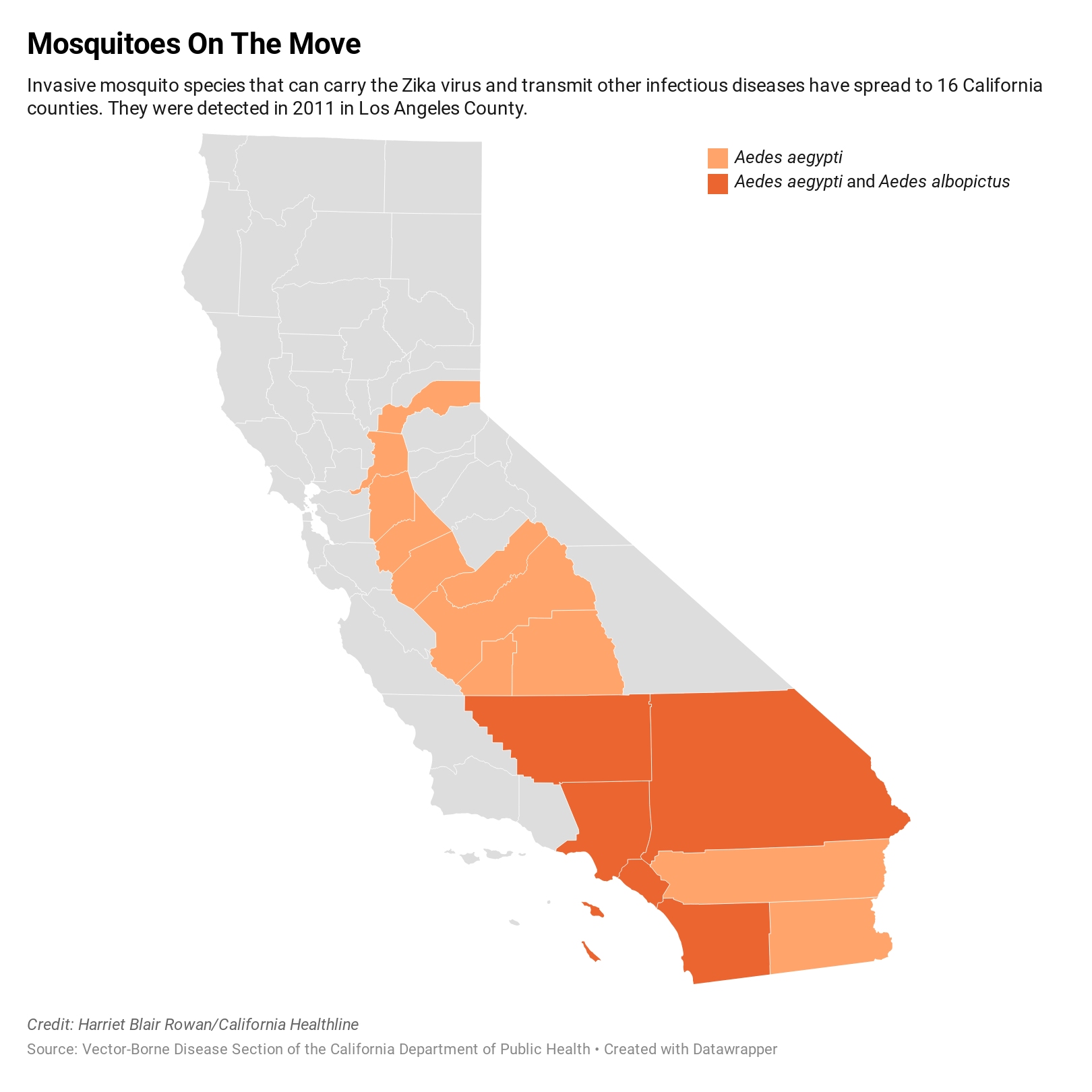

There are now 16 counties where Aedes aegypti, commonly known as the yellow fever mosquito, has been detected, according to the state Department of Public Health. Five of those counties have also detected Aedes albopictus, the Asian tiger mosquito.

These mosquitoes, distinguished from other species because they primarily sip human blood during the day instead of at night, can spread the Zika virus, which infected more than 1 million people during an epidemic that began in 2015 in Brazil. The virus also can spread during sex.

More than 3,000 babies were born with microcephaly in Brazil during the epidemic. Microcephaly is a condition in which a baby’s head is much smaller than expected, and can occur because the baby’s brain has not developed properly.

In California, the invasive mosquitoes were detected in 2011 in Los Angeles County, and since have spread northward into the Central Valley.

Although the invasive mosquitoes now inhabit a large swath of the state, authorities have recorded no cases of “local transmission” of the dangerous viruses, which means there’s no evidence these Aedes mosquitoes in California are carriers. The California residents who have fallen ill with the dangerous viruses became infected during international travel to areas where the viruses are endemic.

But the potential for in-state transmission remains.

“We do have people in California traveling abroad and bringing back those viruses every year, and now that the mosquito is spreading across the state, the risk has increased, but it’s still very low,” said Jeremy Wittie, president of the Mosquito and Vector Control Association of California.

The number of reported travel-associated cases of Zika has dropped from 509 in 2015 and 2016 combined to 25 so far this year, according to the California Department of Public Health.

Public health officials work with people who were infected overseas to minimize the risk that they will spread the virus in the state.

While state and local vector control agencies keep a close eye on these species of Aedes mosquitoes, their biggest concerns are still West Nile virus and St. Louis encephalitis, which are spread by different species of mosquitoes more common in California. This year, there have been 89 human cases of West Nile virus reported in 15 counties, including two deaths, the department said.

Vector control officials also stress the need for public awareness about how Californians can protect themselves and prevent mosquitoes from proliferating. “It’s simple for people to make a few changes to their lifestyle that would limit the spread of these mosquitoes,” Wittie said.

Wittie recommends people check their properties weekly and drain any standing water to limit the places where mosquitoes can reproduce.

Though these mosquitoes can travel only short distances on their own, they can be transported via international and local trade, or even in a car. They thrive in urban and residential areas, unlike other species, because their eggs can survive in dry conditions for months and require just a tiny amount of standing water to hatch.

“These mosquitoes are adept at living in tight spaces with humans,” Wittie said.