A third of the kids had finished their pancakes when camp counselor Bryan “The Lungs” Wegley hopped up to lead them in “The Penguin Song.” The children flapped their arms and shuffled their feet like snazzy Antarctic seabirds.

Later, when the room had grown quiet, another camp staffer showed a Smurf movie for 15 minutes worth of giggles, before everyone dashed off to swim.

For the 37 children attending this annual summer camp in Salinas, Calif., days packed with fun helped make doses of asthma education go down as smoothly as sweetened cough syrup. The kids attended the camp to frolic, but also to better understand the chronic lung disease that makes breathing more difficult for them and about 1 in 6 California children.

“Dust! Cockroaches! Cigarette smoke! Pets!” the kids yelled out in response to a question about what triggers their wheezing, shortness of breath and tightness in the chest. Some of the children, who ranged in age from 6 to 12, said they’d been to the emergency room multiple times. Asthma, if not properly treated, can be fatal.

Most of the children had been diagnosed when they were babies or toddlers and completely dependent on their parents or guardians. As they grow older and become physically less dependent on adults, they need to take more responsibility for managing their disease. Studies show that asthma camps can instill knowledge and encourage habits that help children better control their conditions.

For most of the week, parents dropped their kids off in the morning and picked them up at the end of the day. But one of the highlights of the camp is the sleepover, held at a local elementary school. That’s when kids who want to can spend the night at camp without their parents. For those who do, it’s another step in assuming responsibility for their own health.

“Our camp song says, ‘Your parents are not in charge of your asthma; you’re in charge of your asthma,’” said Sienna Grant, 9, as she climbed a ladder and prepared to swing rung to rung across a jungle gym. She used to be reluctant to stop playing, even for a puff of her inhaler. But now she’s learning “to take things more seriously,” she said.

Asthma camps sprang up in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when there were far fewer medications to treat the condition.

“There was no way to control or prevent asthma,” said Dr. Steven Prager, who is the camp’s medical director and a physician with the Salinas Valley Memorial Healthcare System, one of the camp’s co-sponsors.

Instead of shooing kids out of the house to play, nervous parents often blocked their path, relegating asthmatic children to a summer on the couch, Prager said.

For some children, asthma camp can provide a safe space to play and learn.

“I hear from prior campers and their parents all the time that the camp helped the kids take a more active, productive role in the management of their asthma,” Prager said. Parents reported a decrease in school absences and emergency room visits after their kids attended the program, he added.

Dr. Michael Welch, a physician at Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego, studied the effectiveness of asthma camps a decade ago, but he said there is little research on the topic.

A 2007 study co-authored by Welch found that a year after attending an asthma camp, kids had “assumed greater responsibility for taking their medication.” The study was based on a survey of nearly 1,800 participants at 24 asthma camps around the United States.

Welch noted that numerous camps cater to children with a wide range of chronic illnesses.

“Kids learn right away that they’re not the only ones with this chronic disease, so they [feel] a little less abnormal, which is good for their self-esteem,” he said.

Despite a profusion of camps dedicated to other conditions, the number of asthma camps is dwindling, Welch said. There are 90 asthma camps across the country — a third fewer than a decade ago — serving about 4,000 children, according to Jill Heins Nesvold, executive director of the Consortium on Children’s Asthma Camps.

There used to be at least five asthma camps in California, but in the past few years, two of them — one in Los Angeles and another in San Diego — have closed.

“Funding has been a problem with keeping asthma camps alive,” said Welch, who was the medical director for more than three decades at the now-shuttered San Diego camp.

Part of the problem, he said, is that groups such as the American Lung Association have decided to focus their funding to research and lobbying, diverting it from direct community services like asthma camps.

The Salinas camp is funded by the Salinas Valley Memorial Healthcare System, Children’s Miracle Network (CMN), a nonprofit that raises money for children’s hospitals nationwide, and individual donors. CMN gets most of its funding from corporate donors across a wide range of industries. The financial contributions help make the camp more affordable for families: Parents pay $55 per child, and scholarships are available.

While the Salinas camp has benefited from a solid endowment over the years, “it’s slowly being whittled down,” Prager said. “At the moment, we’re fine, but it’s going to be a challenge in the years to come.”

But as long as asthma camps keep their doors open, children will likely attend.

In the middle of the week, their confidence growing, about two-thirds of the Salinas campers tackled the overnight.

It sounds simple, but “many of these kids have never spent a night away from home,” Prager said. “It’s a big deal … and for the parents sometimes an even bigger deal.”

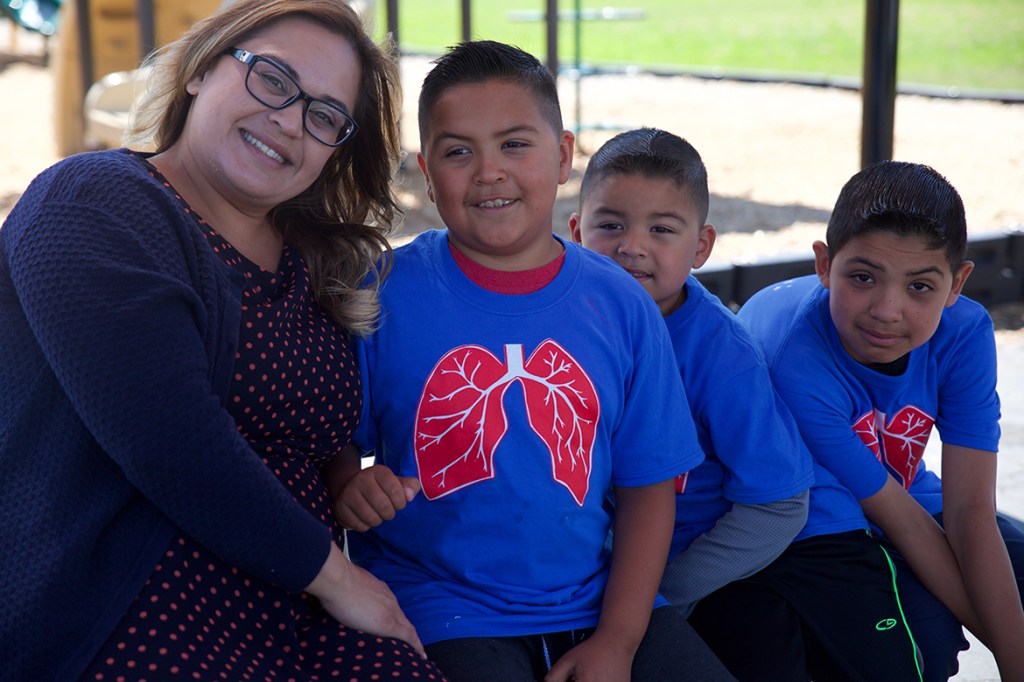

Dario Aldaco, 6, declared he would do the overnight even though his two older brothers — and running buddies — were skipping it.

“I want to do this, even if they don’t want to,” he told his mom, Aidee Aldaco.

“I was anxiety central,” she said. “I asked him, ‘Are you sure? Without your brothers?’”

On the big night, counselors stoked a fire pit near an outside play area and kids gathered around to socialize and munch s’mores. Later, inside the school’s gym, they unrolled sleeping bags and conked out on the floor, with counselors from the local YMCA and Prager nearby.

The next day, when the parents saw their kids had survived without them, they breathed a sigh of relief. On the final day, camp administrators asked the parents to vow that they would not curtail their children’s activities out of fear.

As they said their goodbyes, campers left with a better understanding of their illness, newfound confidence and backpacks full of gadgets and meds to ease their breathing.

Dario came home with the confidence to ask his father not to smoke on the side of the house where the fumes get inside and can trigger his and his brothers’ asthma.

Dario’s older brother, Aaron, 8, who also attended the camp and has mild to moderate autism, began to use a new word: “independent.”

The asthma camp had made him think twice about his mother’s plan to move closer to her children when they go off to college.

“If you move with me,” Aaron asked, “then how am I going to be independent?”

“So,” Aidee Aldaco said with a chuckle, “my husband and I are not going to be able to follow them.”