New state legislation that would allocate $2 million to support valley fever research and monitoring is the most recent effort to increase awareness of the fungal disease, which is typically mild but can be very dangerous in some cases.

The bill, authored by Assemblyman Rudy Salas (D-Bakersfield), would take the money from the state’s General Fund and allot it to an already existing valley fever fund operated by the state’s Department of Public Health. The fund supports research for a vaccine to protect against valley fever. The new money would be used to buy research equipment, develop a tracking method and conduct community outreach, according to the text of the legislation.

Salas’ bill is scheduled to be heard in the Assembly Health Committee next Tuesday.

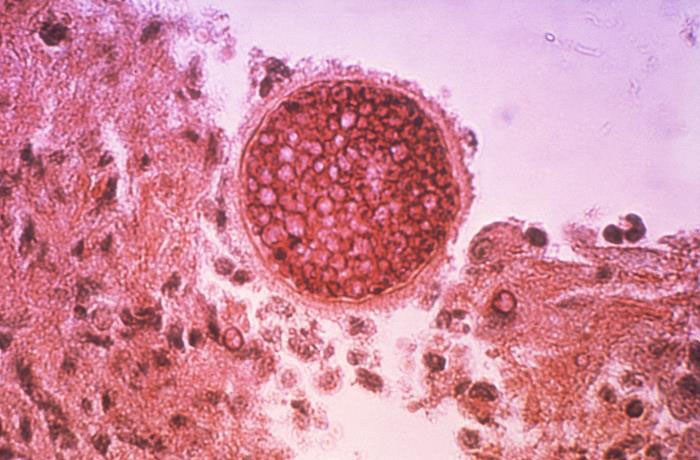

Valley fever is a lung infection caused by inhaling microscopic fungal spores often found in soil. The fungus is known to grow in dry regions of the Southwest, especially in California’s Central Valley and parts of Arizona. People can be infected by breathing in dust that carries the spores, which are lifted into the air by anything that disrupts the soil, including wind, farming or construction.

California reported 3,064 cases of valley fever in 2015. That number was an increase from the previous year, but down from 2011, when the number of valley fever cases across the state hit a record 5,219.

More than a third of the reported cases in 2015 were in Kern County — in the Central Valley — whose main city, Bakersfield, lies about 110 miles north of Los Angeles.

“Valley fever has been reported from almost every county in California, but 75 percent of cases have been found in people who live in the Central Valley, and that is alarming,” Salas said in a press statement.

Rob Purdie, 43, of Bakersfield, Calif., was diagnosed with a serious form of valley fever in 2012. Purdie, pictured with his wife, Wendy, has since become active in helping create awareness about the fungal disease. (Courtesy of Rob Purdie)

The illness is most common in adults, especially people 60 and older, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In most cases, it causes flu-like symptoms that disappear after several days. But sometimes it is more severe and lasts a long time.

More serious cases of valley fever can result in chronic pneumonia, joint pain, ulcers or even meningitis — a potentially fatal infection that causes the membrane encasing the brain and spinal cord to swell.

These more severe cases of valley fever usually require lifelong treatment.

Rob Purdie, a resident of Bakersfield, woke up on New Year’s Day in 2012 to what he calls the worst headache of his life.

A month later, the headaches had not gone away, and his symptoms were multiplying: He started seeing double and having fevers.

Doctors thought at first that Purdie, 43, had a sinus infection or cluster headaches. They eventually diagnosed him with the form of valley fever that causes meningitis. In the five years since his diagnosis, Purdie has tried four oral medications, having to switch because of strong side effects.

“My family thought I was going to die,” said Purdie, who receives injections of medication to fight the disease every three weeks.

Purdie, a board member of the Valley Fever Americas Foundation, a nonprofit group that advocates for research to find a vaccine and a cure, said he is excited about the new bill — mostly because it shows that legislators are paying closer attention to the illness that afflicts him.

“I hope this will open minds and open wallets,” he said.

California counties already are required to report cases of valley fever to the state, but the new bill mandates that the data be submitted in a timely manner, said Matt Constantine, director of public health services in Kern County.

Constantine explained that tracking valley fever cases starts with physicians, who must report them to the county, which then submits the data to the state. But sometimes the county spends too much time verifying that cases of the disease have indeed been collected and reported by physicians, he said.

The bill, by setting specific and standardized guidelines for reporting, is expected to iron out wrinkles in how data are collected and tracked. If it passes, the state’s public health department will be required to post both suspected and confirmed cases online.

Because of their area’s special vulnerability to the disease, Kern County public health officials have boosted public education efforts, Constantine said. Today, the county will launch a campaign to encourage residents to ask their doctors about valley fever. It will also release data showing the number of valley fever cases it had in 2016.