There’s a clear culprit in the rising drug overdose death count in Massachusetts — the synthetic opioid fentanyl. More powerful and more deadly than heroin, fentanyl has sparked a new set of survival rules among people who abuse opioids.

About 75 percent of the state’s men and women who died after an unintentional overdose last year had fentanyl in their system, up from 57 percent in 2015. It’s a pattern cities and towns are seeing across the state and country, particularly in New England and some Rust Belt states.

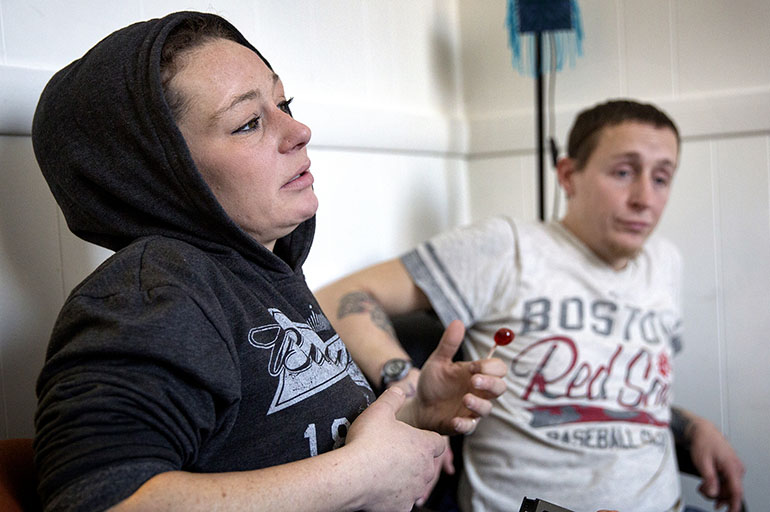

Fentanyl may be especially lethal because it’s strong, it’s mixed with other drugs in varying amounts unknown to the user, and it can trigger an overdose within seconds. “It happens so fast, like instantly, as soon as you do the shot,” said Allyson, a 37-year-old woman who started using heroin in her late teens.

“In the past, [an overdose] was something that you saw happening, like, you could see the person start to slow down, their color would start to turn blue, and then they would go out, within 10 minutes or so,” Allyson said. With fentanyl, there’s no progression, no time to seek help. “Now it’s instant,” she said.

Allyson leaned back in a chair at the AAC Needle Exchange in Cambridge, Mass., and tugged the hood of her gray sweatshirt down to her eyes. Kaiser Health News agreed not to use her full name or the full names of any people in this story who buy illegal drugs, to protect their privacy and future prospects.

Allyson is a regular client at the needle exchange, where manager Meghan Hynes urges everyone to carry naloxone, the drug that reverses an overdose. Hynes, who has become very skilled at CPR, uses her naloxone kit to revive someone every few weeks.

“Recently we had a guy leave the bathroom and all the color just drained from his face, like immediately, and he just turned blue,” Hynes said, describing a typical fentanyl overdose. “I’ve never seen anyone turn blue that fast. He was completely blue and he just fell down and was out — not breathing.”

Hynes bent over the man to pump his heart, but she couldn’t. He was hit with “wooden chest,” a side effect of fentanyl that may be increasing the death toll.

“Your chest seizes up. You literally have paralysis, and that’s obviously really dangerous because if someone needs CPR, you can’t do it,” Hynes said. “And in this situation it spread, so he had lockjaw and his mouth was only open a tiny, tiny bit. And so I could hardly even do rescue breathing for him.”

Breathing for overdose patients is critical because brain cells can die after five minutes without oxygen. Hynes revived the man on the floor with naloxone, which she urges all of her clients to carry. That’s one of what she calls “smart use” rules that she is trying to get the people she trains to follow in this era of fentanyl. Others are to stick to a dealer you know and trust, and to use with a buddy, making sure your buddy’s OK before you inject. There’s also the idea of a test dose, taking a small amount before the full shot.

“But it’s really hard to tell these days, even if you do a tester shot,” Allyson said, because the grains of fentanyl that could kill you aren’t mixed uniformly in a bag. That’s a lesson she learned one death-defying night a few months ago.

Allyson, who is homeless, spent the night in a tent with a friend. She woke up and used the last of a bag from the day before to get herself going.

“And I actually said to my friend, I said, ‘Wow, I can’t believe I only saved myself this much.’ It was a very small amount, like a third of what I did the night before,” Allyson said, shaking her head. “I overdosed on it.”

The friend had enough naloxone in the tent, which was far from a road or hospital, to bring Allyson back from the dead.

Fentanyl is an opioid 50 times more powerful than heroin. There’s a legal, Food and Drug Administration-approved version. But labs in China are churning out cheap versions of fentanyl that dealers are selling on the streets mixed with fillers, heroin or other drugs.

Buyers have no idea how much fentanyl they are getting or how much risk they are taking with every injection. So, these days, drug users who frequent this needle exchange program assume there’s fentanyl in every bag they buy.

“Most of us know that that’s what we’re getting,” said Sean, who started using heroin more than 20 years ago. “And if you don’t believe it, you’re living in a fairy tale world.”

There’s no reliable way for drug users to test the contents of bags bought on the street. Eddie relies on taste.

“It’s slightly bitter, but it’s mainly sweet if it’s fentanyl. If it’s heroin, you can tell right away because it’s got a bitter taste and it’s a long-lasting aftertaste,” Eddie said. “I will not put anything in my arm before I taste it.”

Eddie and Allyson say they try to avoid fentanyl. But when their last dose of drugs starts to wear off, they’ll take anything to avoid withdrawal, which they describe as the flu on steroids with fever, vomiting, diarrhea and high anxiety.

“It literally feels like your skin is crawling off. You’re sweating profusely,” Allyson said. “Your nose is running, your eyes are running. And that’s all you can focus on. You can’t think.”

Some drug users seek fentanyl because it’s a more immediate rush and intense high. But Allyson doesn’t like it. She says a fentanyl high fades much more quickly than heroin’s, which means she has to find more money to buy more drugs and inject more often, which exposes her to more risk.

When fentanyl fades, she and Eddie say, they are more likely to take other drugs. “You’re getting a fast rush but it doesn’t last, so people are mixing,” Allyson said.

At 37, Allyson is having experiences most Americans don’t face until much later in life. “As of two days ago, 30 people that I know have passed away. Basically my entire generation is gone in one year.” Allyson said. “It’s the fentanyl, definitely the fentanyl.”

Older drug users who have been through other epidemics say this moment with fentanyl is the worst they’ve seen.

“Addicts are dying, like, every day. It’s crazy, man,” said a man named Shug, twisting a towel in his hands, his eyes filling with tears. “Nobody seems to give a damn.”

Shug is grateful for the needle exchange facility, which hasn’t lost anyone to an overdose. But on the streets outside, the death toll keeps rising.

This story is part of a partnership that includes WBUR, NPR and Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.