In the state that’s leading the opposition to many of President Donald Trump’s health policies, California voters will face a stark choice on the November ballot: keep up the resistance or fall in line.

The results of Tuesday’s primary have set up general-election contests between candidates — for governor, attorney general, insurance commissioner and some congressional seats — with sharply differing views on government’s role in health care.

The outcome in the Golden State could help shape the fate of the Affordable Care Act and influence whether Republicans in Washington take another shot at dismantling the landmark law.

“For the Affordable Care Act, California is a bellwether state,” said David Blumenthal, president of the Commonwealth Fund, a New York-based health policy research organization. If California voters don’t elect more Democrats to Congress, it will be harder for the party to gain legislative control and “the Affordable Care Act will continue, as it has been, to be under attack from an empowered Republican majority,” he said.

Despite being targeted for voting last year to repeal the ACA and cut Medicaid funding, several Republican incumbents performed well at the polls in California.

“California was supposed to lead the blue wave, but that’s not what we saw” in the primary, said Ivy Cargile, an assistant professor of political science at California State University-Bakersfield.

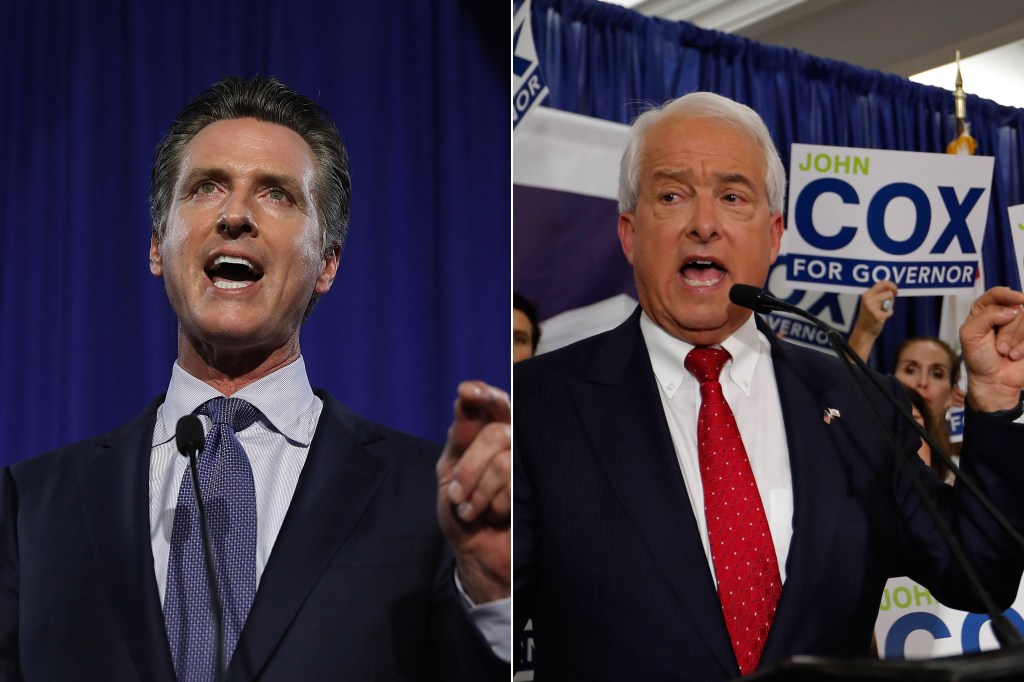

In the California governor’s race, Democratic front-runner Gavin Newsom quickly sought to cast the November contest as a referendum on Trump and his effort to undo much of President Barack Obama’s legacy, particularly on health care.

A series of Trump tweets endorsing Republican candidate John Cox, a multimillionaire real estate investor, helped propel the political outsider to the general election.

“It looks like voters will have a real choice — between a governor who will stand up to Donald Trump and a foot soldier in his war on California,” Newsom said Tuesday night to supporters in San Francisco.

California has embraced the federal health law enthusiastically and stands to lose more than any other state if the ACA is gutted. About 1.5 million Californians buy coverage through the state’s Obamacare exchange, Covered California, and nearly 4 million have joined Medicaid as a result of the program’s expansion under the law.

Newsom, a former San Francisco mayor and the current lieutenant governor, has pledged to defend the coverage gains made under the ACA. He has vowed to go even further by pursuing a state-run, single-payer system for all Californians.

Newsom won the primary with 33 percent of the vote and Cox placed second with 26 percent. Some mail-in votes and provisional ballots continue to be counted.

Cox has slammed Newsom and fellow Democrats for imposing government controls on health care that he says make coverage too expensive for families. He said he isn’t interested in defending the Affordable Care Act and that, if the law is scrapped, millions of Californians can go into high-risk insurance pools — an idea that predates the health law.

Andrew Busch, a government professor at Claremont McKenna College, said the political divide over health care has grown even wider this year as single-payer has gained support from mainstream Democrats in California.

“I’d say the Republican candidates are pretty much where the Republicans have been, but the Democratic candidates have shifted to the left, so the choice is starker than it has been,” Busch said.

Heading into Tuesday’s primary, it wasn’t clear that California voters would face such drastically different choices on the November ballot. Under the state’s primary system, the top two vote-getters, regardless of party affiliation, advance to the general election. That left many experts predicting single-party matchups across the state.

But that scenario also didn’t pan out in the race for attorney general, a position that has played a key role in California’s resistance politics since Trump was elected. Democratic incumbent Xavier Becerra, who has become a national leader against Trump’s agenda, will face off against Republican Steven Bailey in the fall.

Becerra has filed more than 30 lawsuits on health care and other issues since taking office in January 2017.

Bailey, a criminal attorney and former judge, has blamed the Affordable Care Act for driving up health care costs, and he favors less industry regulation. He also has criticized Becerra for fixating too much on Trump.

“Just because a tweet comes out of Washington, it doesn’t require a lawsuit to be filed the next day,” Bailey said.

Health care could also play a role in several of California’s congressional races. Democrats are trying to win back control of the House, in part to better block Republican efforts to roll back the ACA.

“The actions of the Trump administration, the elimination of the individual mandate and its impact on markets will become more of an issue,” said Chris Jennings, a former health care adviser in the Obama administration. “The conservative caucus has been forcefully advocating for another aggressive return to the repeal effort.”

One of the most-watched races nationally is in a district of California’s San Joaquin Valley where Republican incumbent Jeff Denham drew several Democratic opponents after voting to repeal the health law last year — as did all of California’s Republican House members.

Denham led a crowded primary field with 38 percent of the vote Tuesday. Democrat Josh Harder is holding on to second place with nearly 16 percent, just ahead of a Republican challenger. The results are pending until late-arriving ballots are counted.

Harder said the Republicans’ repeal-and-replace effort on health care was a major reason he decided to run. He made it a centerpiece of his campaign and ran ads criticizing Denham for voting to take away coverage from thousands of his constituents. About 40 percent of residents in this Modesto-area district are enrolled in Medicaid, the government insurance program for the poor and disabled.

Denham has defended his repeal vote, saying that patients’ access to doctors has only gotten worse since coverage was expanded under the ACA. In a statement last year, Denham said, “coverage does not necessarily equal care and families must resort to overflowing emergency rooms to be seen.”

But Dan Schnur, a Republican political strategist who teaches at the University of Southern California and the University of California-Berkeley, said health care has gone from a negative to a positive for Democratic candidates, who have spent the past several elections defending Obamacare.

“As a result, they’re doing everything they can to emphasize the health care debate rather than run away from it,” he said.